How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare (19 page)

Read How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare Online

Authors: Ken Ludwig

Tags: #Education, #Teaching Methods & Materials, #Arts & Humanities, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #General

Romeo is comparing Juliet to the sun, as though she were creating the light that has just spread across the garden. He then contrasts the sun with the moon. As your children know from

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

, the moon is a symbol of romance. Yet Juliet is so beautiful that the romantic moon is envious of her. Have your children break the lines into phrases and memorize them one at a time:

It is the East

,

and Juliet is the sun

.

Arise, fair sun

[i.e., Juliet],

and kill the envious moon

,

Who is already sick and pale with grief

That thou, her maid, art far more fair

[beautiful]

than she

.

The moon is so jealous that it is sick and has turned pale. Turn these lines into a game: “Why is the moon sick and pale with grief?” Because her maid, the sun, and by extension Juliet, is more beautiful than she is. Juliet is more beautiful than the moon itself!

Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon

,

Who is already sick and pale with grief

That thou, her maid, art far more fair than she

.

Have your son or daughter really act out the next four lines. Romeo is alive with love. He is tingling with emotions. His words are bright, and they sound as clear as a trumpet call:

It is my lady. O, it is my love!

See how she leans her cheek upon her hand

.

O, that I were a glove upon that hand

,

That I might touch that cheek!

The metaphor here is beautiful in its simplicity. If he were her glove, he could be touching her cheek. He is besotted.

O, that I were a glove upon that hand

,

That I might touch that cheek!

Juliet

And now it’s Juliet’s turn.

O, Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?

Ask your children what this line means. I’ll bet they get it wrong. My guess is that they’ll say it means “Where are you, Romeo?” But it doesn’t mean that at all. In Elizabethan times, the word

wherefore

meant “why.” So Juliet is saying, “O, Romeo, Romeo, why do you have to be named

Romeo—

and therefore a Montague!”

O, Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?

“O, Romeo, Romeo, why are you Romeo?!” Notice that there is no comma after the word

thou

.

Deny thy father and refuse thy name

,

Or, if thou wilt not, be but sworn my love

,

And I’ll no longer be a Capulet

.

In other words, “Deny your heritage and renounce your name. Or, if you won’t do that, but if you will swear to be my love [

be but sworn my love

], then I’ll renounce

my

name and no longer be a Capulet.”

Deny thy father and refuse thy name

,

Or, if thou wilt not, be but sworn my love

,

And I’ll no longer be a Capulet

.

Meanwhile, Romeo is down below and says to himself

Shall I hear more, or shall I speak at this?

Juliet continues:

’Tis but thy name that is my enemy

.

…O, be some other name!

What’s in a name! That which we call a rose

By any other word would smell as sweet

.

Have your children break this section down into three parts and learn them one at a time.

’Tis but thy name that is my enemy

.

…O, be some other name!

What’s in a name!

That which we call a rose

By any other word would smell as sweet

.

The last phrase has become one of the most famous epigrams of all time (though it is usually misquoted):

a rose by any other word would smell as sweet

.

The Rest of the Story

After the Balcony Scene, the story moves ahead at a remarkably speedy clip. That is one of the hallmarks of this play: It rushes forward—like young love—and never stops till the end. (In all the canon, only

Macbeth

has this same sense of relentless self-propulsion.) The day after they swear their love on the balcony, the lovers are secretly married by a well-meaning friend of Romeo, Friar Laurence. The Marriage Scene ends Act II; and up until this time, the play reads like a comedy. Unfortunately for the lovers, however, events soon turn more dangerous.

Romeo meets his best friend, the volatile Mercutio, on the street, and a moment later Juliet’s surly cousin Tybalt walks by. Tybalt provokes a fight and kills Mercutio. Romeo is so angry that he grabs a sword, challenges

Tybalt, and kills him—Juliet’s cousin—at which point the Prince, tired of all the feuding, banishes Romeo from Verona.

That night in Juliet’s bedroom, Romeo and Juliet consummate their marriage. But the next morning Romeo flees, and the lovers have little hope of ever seeing each other again. To make matters worse, Juliet’s parents insist that she marry Paris in just three days’ time. Friar Laurence, however, has a plan. He will give Juliet a potion to make her appear dead on the morning of her wedding; then he will get word of the trick to Romeo, and Romeo will arrive at the Capulet tomb and carry Juliet off forever. Needless to say, the plan goes awry.

Romeo never gets word of the potion. When he arrives at the tomb and finds Juliet “dead,” he kills Paris, then kills himself. Then Juliet awakes, sees Romeo dead, and kills herself. The final moments of the play find the parents of the deceased lovers vowing to end their senseless feud.

Juliet’s Love

Romeo and Juliet

is filled with glittering language. It is Shakespeare at his most youthfully exuberant, his poetry filled with rhymes and puns and extravagant images that only a young man would dare employ so unselfconsciously. For example, in the balcony scene, Juliet says to Romeo:

My bounty is as boundless as the sea

,

My love as deep; the more I give to thee

,

The more I have, for both are infinite

.

Throughout the play we witness ideas and imagery, rhythm and sound, uniting to create love poetry as beautiful as any that has ever been written. As Northrop Frye puts it, the moment Romeo and Juliet meet, “The God of Love … has swooped down on two perhaps rather commonplace adolescents and blasted them into another dimension.”

Shakespeare has a magnificent way of showing us how it happens, and he does it, naturally, through language. Before Juliet meets Romeo, she speaks with the simple correctness of a proper young lady. In an early

scene, for example, Juliet’s mother asks her how she would feel about getting married, and Juliet answers without passion:

It is an honor that I dream not of

.

Then comes the sea change. After the lovers are married, Juliet’s voice becomes urgent with sexual desire. It almost sizzles off the page. Here is Juliet as she waits for Romeo to join her in her room after the wedding.

Gallop apace, you fiery-footed steeds

,

Towards Phoebus’ lodging: such a wagoner

As Phaethon would whip you to the west

,

And bring in cloudy night immediately

.

A

steed

is a horse;

Phoebus

is the sun god; a

wagoner

is a charioteer; and

Phaethon

was the son of Phoebus who was allowed to drive the chariot of the sun, then lost control of the runaway horses. Juliet’s desire is galloping and out of control, which is just what she hopes from the horses of the sun, so that they’ll rush home and allow night to arrive.

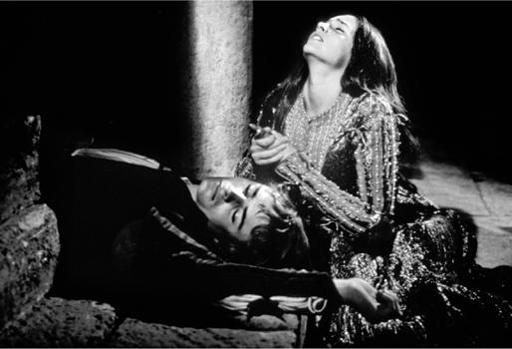

Franco Zeffirelli’s

Romeo and Juliet

, with Leonard Whiting as Romeo and Olivia Hussey as Juliet

(photo credit 20.2)

In another part of the speech, she says that when Romeo dies, night should cut him into little stars because his brightness will make heaven look all the finer by contrast:

Come, gentle night, come, loving, black-brow’d night

,

Give me my Romeo; and, when he shall die

,

Take him and cut him out in little stars

,

And he will make the face of heaven so fine

That all the world will be in love with night

And pay no worship to the garish sun

.

Dazzling words coupled with remarkable thoughts. This is young Shakespeare’s first masterpiece.

Shakespeare’s Life and an Overview of His Work

S

hakespeare” has become such an icon for the ages, representing all that is considered literate, intellectual, and stage-worthy in our civilization, that it is easy to forget that the man himself lived a fairly normal life, at least externally. (Internally he must have lived a thousand lives, and that, in a sense, is the subject of this book.) He was born in the town of Stratford-upon-Avon in south-central England in 1564, and he died there in 1616 at the age of fifty-two.

1564–1616

Urge your children to memorize these dates. Repeat them aloud together several times. Skip a day and then go back to them. They represent the high point of the English Renaissance. They’re also connected to the Renaissance in Europe: Galileo was also born in 1564, Michelangelo died in 1564, and Cervantes died in 1616.

1564–1616

These dates will be useful reference points for your children for the rest of their lives.

The specific date of Shakespeare’s birth is said to be April 23, 1564, but there is no record of the exact day. We do know that he was baptized at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford on April 26, 1564; and since baptism in those days took place two to three days after birth, April 23 has been assumed to be the date of Shakespeare’s birth. The choice is also symbolic: Shakespeare died on April 23, 1616 (fifty-two years later to the day), and the patron saint of England is Saint George, whose saint’s day is also April 23.

True Story

Several years ago one of my plays was about to go into rehearsal at a studio of the Royal Shakespeare Company in suburban London. As we approached the door of the studio, the director turned to me and said, “Unlock the door.” I looked at the lock and saw that it was one of those square silver boxes with rows of numbered buttons that you have to push in the proper sequence. I looked to the director for guidance, but he just waited patiently. This was a test. I thought for a moment and then pushed

0 4 2 3 1 5 6 4

April 23, 1564

The door sprang open, the director raised an eyebrow in approval, and we began the rehearsal.