How to Think Like Sherlock (10 page)

Read How to Think Like Sherlock Online

Authors: Daniel Smith

Sherlock Holmes – his limits

1. Knowledge of Literature. – Nil.

2. Knowledge of Philosophy. – Nil.

3. Knowledge of Astronomy. – Nil.

4. Knowledge of Politics. – Feeble.

5. Knowledge of Botany. – Variable. Well up in belladonna, opium, and poisons generally. Knows nothing of practical gardening.

6. Knowledge of Geology. – Practical, but limited. Tells at a glance different soils from each other. After walks has shown me splashes upon his trousers, and told me by their colour and consistence in what part of London he had received them.

7. Knowledge of Chemistry. – Profound.

8. Knowledge of Anatomy. – Accurate, but unsystematic.

9. Knowledge of Sensational Literature. – Immense. He appears to know every detail of every horror perpetrated in the century.

10. Plays the violin well.

11. Is an expert singlestick player, boxer, and swordsman.

12. Has a good practical knowledge of British law.

Holmes played upon the alleged deficiencies in his knowledge at various times. In ‘The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor’, he insisted, ‘I read nothing except the criminal news and the agony column’; when challenged on his ignorance of the solar system, he demanded of Watson: ‘What the deuce is it to me?’

We should take all this with a pinch of salt. Holmes was focussed on the job at hand and he thus attempted to clear his mind of intellectual clutter irrelevant to a particular task. Knowledge for Holmes was purely utilitarian (something quite at odds with the Victorian era’s love of knowledge for its own sake). ‘Holmes is a little too scientific for my tastes,’ Stamford told Watson before introducing him to Sherlock.

‘It approaches to cold-bloodedness. I could imagine his giving a friend a little pinch of the latest vegetable alkaloid, not out of malevolence, you understand, but simply out of a spirit of inquiry in order to have an accurate idea of the effects. To do him justice, I think that he would take it himself with the same readiness. He appears to have a passion for definite and exact knowledge.’

Would knowledge of the solar system have assisted Holmes greatly in solving any of his cases? Unlikely. Do we really believe that he didn’t have at least a rudimentary grasp of the structure of the solar system? Not really. In ‘The Greek Interpreter’ he talks with confidence on the ‘causes of the changes of the obliquity of the ecliptic’, suggesting Watson was rather off beam in assuming a lack of astronomical knowledge.

Then there is the assertion about his breadth of reading. Critic E. V. Knox noted that in the course of the stories we see Holmes ‘quote Goethe twice, discuss miracle plays, comment on Richter, Hafiz and Horace, and remark of Athelney Jones: “He has occasional glimmerings of reason.

Il n’y a pas des sots si incommodes que ceux qui ont de l’esprit!

”’ Elsewhere he mentions Tacitus, Flaubert, Thoreau and Petrarch. Hardly suggestive of ‘nil’ knowledge of literature.

Holmes was also an innovator in several academic areas. Among the literature he produced were monographs on different types of tobacco ash, the polyphonic motets of Lassus, ciphers, document-dating, tattoos, tracing footprints, and the impact of trade upon the form of the hand. To say nothing of his ‘Book of Life’ or his Practical Handbook of Bee Culture. ‘You have an extraordinary genius for minutiae,’ Watson told him once. Indeed.

In conclusion, despite Watson’s occasionally disparaging words, the extent of Holmes’s knowledge was almost certainly as vast as you might expect. Perhaps his greatest genius was to be able to streamline his knowledge in the moment so that whatever was swirling around in his mind had, in Conan Doyle’s own words, ‘real practical application to life’.

Quiz 13 – Holmes Trivia

Sherlock Holmes overcame innumerable challenges by arming himself with the necessary knowledge to do so. By reading this book, it is assumed that you want to think like Sherlock. But how much do you actually know about him? Test yourself with this quiz.

1.

What was Dr Watson’s first name?

2

. Which famous family of French painters was Sherlock related to?

3.

Who introduced Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson?

4.

What was Irene Adler’s job?

5.

What was the name of Dr Watson’s wife whom he met in

The Sign of Four

?

6.

Who was the ‘Napoleon of crime’?

7.

Where had Dr Watson qualified as a doctor?

8.

What is the name of Sherlock’s brother?

9.

At which Pall Mall club was this brother a member?

10.

Where did Sherlock apparently fall to his death in 1891?

11.

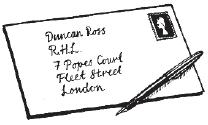

What was Sherlock’s London address?

12.

What job title did he give himself?

13.

Where did he settle in his retirement?

14.

Where did Sherlock famously keep his stash of tobacco?

15.

Holmes donned two disguises in

A Scandal in Bohemia

. Can you name one of them?

16.

In which county was Baskerville Hall?

17.

Who was the leader of the Baker Street Irregulars?

18.

Which story details Holmes’s first criminal investigation?

19.

What is unusual about ‘The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier

’

and ‘The Adventure of the Lion’s Mane’?

20.

Where did Dr Watson keep papers concerning Holmes’s other cases?

Obtaining Data

‘“Data! data! data!” he cried impatiently. “I can’t make bricks without clay.”’

‘THE ADVENTURE OF THE COPPER BEECHES’

In his pursuit of the data vital to his professional occupation, Holmes relied on three main sources: the wealth of information stored within his brain, clues specific to a particular case that he discovered ‘in the field’, and reference sources.

Let us start by talking about his skill as a gatherer of clues. In an age when forensic detective work was a relatively new phenomenon, Holmes could read a crime scene and rake it for evidence like no other. He was way ahead of his time in appreciating the use of fingerprints, footprints, bloodstains and the like, as well as the time-sensitive nature of evidence-gathering. Here we may conjure the classic image of Holmes as he ‘whipped a tape measure and a large round magnifying glass from his pocket.’ In this respect, he often found himself battling the plods from the official police, who were less sensitive to preserving evidence. In ‘The Boscombe Valley Mystery’, he exclaimed of the crime scene: ‘Oh, how simple it would all have been had I been here before they came like a herd of buffalo and wallowed all over it.’

Thankfully, forensics plays a much greater role in modern detection work and the police are extremely well-drilled in its demands. While police forces around the world each have their own guidelines, here are a few general tips on how forensic investigators go about their work:

Approach a crime scene with caution. Be aware of potential dangers – such as the on-going presence of a criminal or dangerous substances. If there are any victims at the scene, they are the priority and you should seek out assistance for them in the first instance.

Secure the scene at the earliest opportunity (with rope or tape) to avoid contamination of evidence. This may offer the best hope of retrieving key evidence. After an initial survey, log all potentially useful information.

If there are any witnesses, be sure to get their statements. Take a note of all comings and goings at the scene.

Document the position of potential pieces of evidence. If a camera is not to hand, make drawings or keep notes.

Bring in the relevant experts for jobs such as fingerprint sweeping or bloodstain analysis.

Any evidence to be taken away should be handled as delicately as possibly (hands should be gloved at all times). Each item of evidence must be individually bagged and labelled.

An official record of the crime scene investigation should be written up as quickly as possible and handed over (with a briefing where necessary) to the investigating officer in charge.

However closely you have read this book and feel you are prepared to follow in the Great Detective’s footsteps, do not insert yourself into a criminal investigation. Leave it to the police!

Once Holmes had gleaned as much as he possibly could from a crime scene, he would often consolidate his investigation by further background research of his own. This sometimes manifested itself in the form of experimentation. Holmes was infamous (particularly with Mrs Hudson) for the ‘malodorous experiments’ he undertook in his rooms and he was also variously witnessed beating cadavers to learn how far bruises may be produced after death and attempting to ‘transfix a pig’ with a single blow.

Then there are his indexes and books of reference. Watson described how Holmes had ‘a horror of destroying documents’, and his book shelves must have bowed under the weight of all the documentation he retained and cross-referenced. Had he lived today, Holmes may have regarded the era of the internet and the all-seeing search engine as his personal paradise. We might only imagine his joy at the prospect of being able to locate virtually any piece of information by typing a few words on a keyboard.