Authors: Neal Bascomb

Hunting Eichmann (28 page)

When the plane began its descent to Ezeiza Airport, Klein was already beginning to get hold of both his anxieties over the operation and his emotions regarding the past. But when flashbulbs popped the moment he stepped onto the tarmac, he jumped. Both he and Shimoni thought the mission had already been compromised, and them with it, but they soon realized that a photographer was just trying to make a buck off the tourists. The situation's absurdity provided a welcome relief.

In the terminal, they were met by Luba Volk, her husband, and an individual from the Israeli embassy, who introduced himself as Ephraim Ilani. Volk sensed straightaway that her two El Al colleagues were distracted and worried. Already that morning, her suspicions about their coming to Argentina had been piqued when Ilani, whom she knew only slightly, had telephoned, saying that he wanted to follow her husband and her to the airport to meet Shimoni and Klein. Now Ilani explained to Shimoni and Klein that he had booked a different hotel from the one Volk had reserved for him. Volk and her husband drove Shimoni and Klein to the second hotel, noticing again how anxious they seemed. On the ride home, she remarked to her husband, "There is something more going on with this flight than just the delegation."

Later that night, Klein and Shimoni sat down with Isser Harel in a café in the city. The Mossad chief spoke in a very matter-of-fact tone. Shimoni would be departing in a few days, leaving Klein on his own. "What your job really entails," Harel said, "is to make all the arrangements for the flight."

He spoke at length about how Klein would be responsible for everything from the plane's arrival to its departure. Klein needed to establish relations with the relevant Argentine ministries, as well as the service companies and other airlines that would accommodate El Al, since it had no infrastructure in the country. Furthermore, Harel wanted Klein to survey the airport, its facilities, and its customs and passport procedures and to recommend the best way to get their prisoner on board the plane.

"We're not here just to do a job," Harel said, sensing that Klein needed some encouragement. "This is the first time the Jewish people will judge their murderer."

On May 3, Yaakov Gat spent yet another morning in a café, expecting Peter Malkin and Rafi Eitan to walk through the door. Yet again he was disappointed. They were late. Moshe Tabor, who had landed the day before, had met with them in Paris, but he did not know the reason for their delay. If they had been caught attempting to get into Argentina with false passports, Ilani, at the embassy, had yet to receive word.

The team forged ahead without them, continuing their surveillance of Eichmann, tracking his movements to and from work to see if there was a better spot to grab him than outside his home. They applied themselves to securing proper safe houses, and after forty-eight hours of intensive searching, their efforts were rewarded with two buildings. Both happened to be owned by Jewish families, although they had no idea why Medad wanted to rent their properties.

The first was located in a quiet neighborhood of Florencio Varela, a town eighteen miles southwest of Buenos Aires. The large two-story house, code-named Tira (palace), had several advantages: easy access to both the capture area and the airport, an eight-foot wall around the property, a gated entrance, no caretaker, and a rear garden and veranda obscured by trees and dense shrubs. It was by no means perfect, however. The property was situated on a long, narrow plot of land with neighbors on both sides. The house lacked an attic or basement to hide the prisoner, and the utilitarian layout of the rooms, all built with thick walls, made it complicated to construct a secret room to protect against the eventuality that the police raided the place. Still, it would serve well as a backup to the other safe house, which they considered perfect in every way but one.

Code-named Doron (gift), their second find was more a villa than a house. The architect had designed a sprawling affair with several wings on multiple levels and a maze of rooms unpredictable in their placement, size, configuration, and entrance. With little effort, they could build a secret chamber that would take the police hours, if not days, to find. The villa was a couple of hours from Garibaldi Street, and there were several routes into the area. The extensive manicured grounds surrounded by a high stone wall also limited spying by nosy neighbors. The only drawback was that a gardener serviced the property, but they felt that they could keep him away.

The team now focused completely on planning the capture itself.

After their first day's work in Buenos Aires, Shimoni and Klein met with Harel at a café, their faces revealing their extreme agitation. Shimoni explained that the Argentine protocol office was not prepared to welcome the Israeli delegation until May 19, a week later than they had expected. There was no way to negotiate with them without drawing too much attention to the flight.

After the El Al officers left, Harel discussed the repercussions with Shalom. Either the team would have to postpone the capture date or risk holding their captive for ten days, until the plane could take off on May 20. Neither was a good option. Delaying increased the odds that Eichmann would change his routine or, much worse, that he would discover that he was being shadowed and run. Extending his imprisonment in the safe house gave those looking for him—whether his family, the police, or both—more time to find him, and the team would have to endure waiting day after day in seclusion.

Shalom felt that they should postpone the operation by at least a few days. Harel feared that even this minor delay would give Eichmann a chance to elude their grasp. Needing time to think—and hoping to discuss the situation further with Rafi Eitan if and when he arrived—Harel put off making a decision. One thing was certain: the news heightened the risks for everyone involved.

On the evening of May 4, Eitan and Peter Malkin finally arrived in Buenos Aires. Only the doctor and the forger had yet to arrive to complete the team. Eitan and Malkin had been held up in Paris with documentation problems, then Eitan had been bedridden with food poisoning, and they had had difficulty rebooking a flight.

Shalom collected them at their meeting place in a 1952 Ford clunker. With the operation only six days away, they wanted to go straightaway to San Fernando.

As they drove north, a light rain fell and a cold, blustery wind picked up. Knowing the roads in Buenos Aires thoroughly by this point, Shalom took them to San Fernando by the shortest route. On the way, he updated the new arrivals on the operation. By the time they neared the neighborhood, the drizzle had turned into a downpour, but Malkin still recognized some of the landmarks and streets he had studied in Aharoni's reports. Suddenly, Shalom came to an abrupt stop. They were on a street running parallel to Garibaldi. Two young soldiers materialized on either side of the car. One held a red flashlight; both were armed and carrying truncheons. Shalom stayed calm; he had run across enough roadblocks and spot checks to know that this was routine. In his pidgin Spanish, he explained to one of the soldiers that they were tourists, searching for their hotel. The soldier did not reply, focusing his light first on Shalom, then on the license plate. Rain streamed off the brim of his hat as he contemplated whether they were a threat. After an age, he waved them on, to the relief of the three Israelis.

Several blocks away, Shalom pulled over to the side of the road. "We'd better leave the car here ... I'd hate for those soldiers to see it again."

Within an instant of exiting the car, they were drenched from head to foot. Malkin hiked across a field pocked with mud, cursing that he had worn a suit and dress shoes. But when he reached the lookout post on the railway embankment, he forgot about everything except the house on which his binoculars were now trained. The post was perfectly positioned, and Malkin was able to see Eichmann's wife clearly through the front window. Then he checked his watch. According to Shalom, Eichmann would arrive within the next few minutes.

Since the first day Malkin had read the file on the Nazi, his presence had loomed ever larger and more evil. In Vienna alone, on his first assignment to force the Jews out of Europe, Eichmann had shown his true nature. He enjoyed striding through the Palais Rothschild, where the Jews lining the hallways retreated from him in fear. He also enjoyed publicly humiliating the city's Jewish leaders by striking them across the face or calling them "old shitbags" in meetings. After the pogrom led by SS men in civilian attire, during which forty-two of Vienna's synagogues were set afire and more than two thousand families were driven from their homes, Eichmann was remorseless, arriving at the Jewish community's headquarters to announce that there had been "an unsatisfactory rate of disappearance of Jews from Vienna." Already in 1938, the thirty-two-year-old reveled in being called a "bloodhound."

Reading about Eichmann's activities had only started the process of demonizing him for Malkin. His fear of failure when it came to grabbing Eichmann also played a part. But the greatest factor was confronting his own family's loss in the Holocaust. Before Malkin left Israel, he visited his mother and, for the first time, asked her what had happened to his sister Fruma. He learned that she had attempted to get out of Poland with her family but that her husband had not been convinced that they needed to leave. Malkin spent most of that night staring at his sister's photograph and reading the letters she had sent their mother before being shot in a camp outside Lublin. In each one, Fruma had asked if he was all right, while all along she and her family were running out of time because the killing machine that Eichmann had helped build was coming for them.

Now, his hands numb from the cold and rain, Malkin held the binoculars up to his face, and a thousand thoughts about Eichmann, his sister, and the operation coursed through his brain. He saw a bus approach down Route 202. It stopped at the kiosk, and a man in a trench coat and hat descended onto the street. In the darkness, Malkin was unable to see his face, but there was something about the man's deliberate, leaning stride that matched his vision of Eichmann.

"That's him," Shalom whispered.

Malkin stared down from the embankment. The sight of the lone figure walking through the driving rain burned in his mind: this was the man he had come to capture. Malkin was already calculating the type of takedown he would use and where on this stretch of road he would make his move.

What neither Malkin nor Eitan knew was that Zvi Aharoni had traveled for part of the way with Eichmann that night. In an attempt to track where their target boarded bus 203, Aharoni had gone to the station in Carupa, eight stops from San Fernando, dressed in overalls like many workers in the area. As he boarded the old green and yellow bus, he caught sight of Eichmann seated in a row halfway down the aisle, among the throng of factory workers and secretaries. Aharoni made sure to look away, so as not to be caught staring, and handed the driver the 4 pesos for the ticket. If the driver asked him a question in Spanish, he would surely draw attention to himself. Fortunately, he did not.

As Aharoni walked down the aisle, he noticed that the only empty seat was directly behind Eichmann, who was oblivious to Aharoni as he passed. He slid into the seat, barely noticing the steel springs that jutted through the worn leather seats. Aharoni was close enough to be able to reach out and put his hands around the Nazi's neck. As the bus shuddered to a start, he felt a rush of emotion that left him physically weak. Severely distressed, he could not wait to get off the bus at the San Fernando station. If there was ever any doubt in his mind that they were after more than just a man, this brief encounter dispelled that notion. They were closing in on evil itself.

The identifying photo of

Eichmann, found by his

pursuers in the late 1940s

Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz /

Art Resource

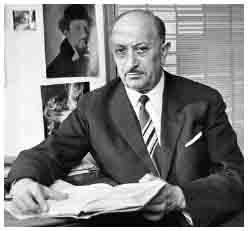

Simon Wiesenthal, Nazi hunter

©

UPPA / Topham / The Image Works

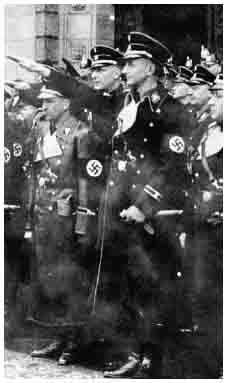

Eichmann during the war

©

Roger-Viollet / The Image Works