I am a Genius of Unspeakable Evil and I Want to be Your Class (2 page)

Read I am a Genius of Unspeakable Evil and I Want to be Your Class Online

Authors: Josh Lieb

BOOK: I am a Genius of Unspeakable Evil and I Want to be Your Class

8.92Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

And poor Mr. Moorhead thinks I’m the dumbest boy in his English class.

The bell rings. Moorhead gives me one last pitying glance, then strolls back to the board. “Read the next chapter for tomorrow, people. And remember—nominations for student council have to be submitted at your next homeroom.” He smiles at Jack Chapman, who lowers his handsome head modestly and runs a bashful hand through his soft and kinky hair. Jack exits with the throng, enduring much backslap ping and people yelling, “You got my vote, Jack.” I pretend to fumble with my books so I can see what happens next.

It’s lunchtime. As always, Moorhead reaches into his shirt pocket for his pack of cigarettes and shakes one out. He does this right after class, even though he can’t smoke in the classroom, even though he can’t smoke in the school. He must walk a legally mandated ten yards off school property before he can smoke his death stick. But he always pulls it out right after class.

He looks at the cigarette with longing . . . then with surprise. He holds it close to his weak, middle-aged eyes. There’s a message typed neatly on the little tube:

YOUR DIET ISN’T WORKING

.

YOUR DIET ISN’T WORKING

.

Moorhead stares at the cigarette a moment, then looks up with suspicion and fury. But the only people he sees are me and Pammy, who is also dawdling, but for very different reasons.

4

4

Pammy gives him a simpering smile, which he ignores. I, near-retard that I am, am singing a song to myself as I look for my pencil under the desk. The only words to the song are “

Three, please. Can I see threeeee pretty pictures. . . .

” Moorhead gives me a scornful glance before hurrying out of the room.

Three, please. Can I see threeeee pretty pictures. . . .

” Moorhead gives me a scornful glance before hurrying out of the room.

But the look of terror on his face in that single, unguarded moment of surprise is truly a beautiful, beautiful thing.

There will be three full-color photographs of that moment waiting for me by the time I get to my locker.

Chapter 2:

CHILDREN ARE VERMIN

Let me explain children to you.

First off, I call them “children,” not “kids.” I am a child, and I am not ashamed to be one; time will cure this unfortunate condition. “Kid” is the cutesy name adults call children because they think “child” sounds too scientific and clinical. I refuse to call myself by their idiotic pet name. Your grandmother might call you “Snugglepants Lovebottom,” but that’s not how you introduce yourself to strangers.

5

5

I also refuse to use terms like “teen,” tween,” and etc. I find them patronizing and putrid. They are fake words, used to disguise the truth—that anyone under the age of eighteen is legally (and that’s the only thing that matters) a child.

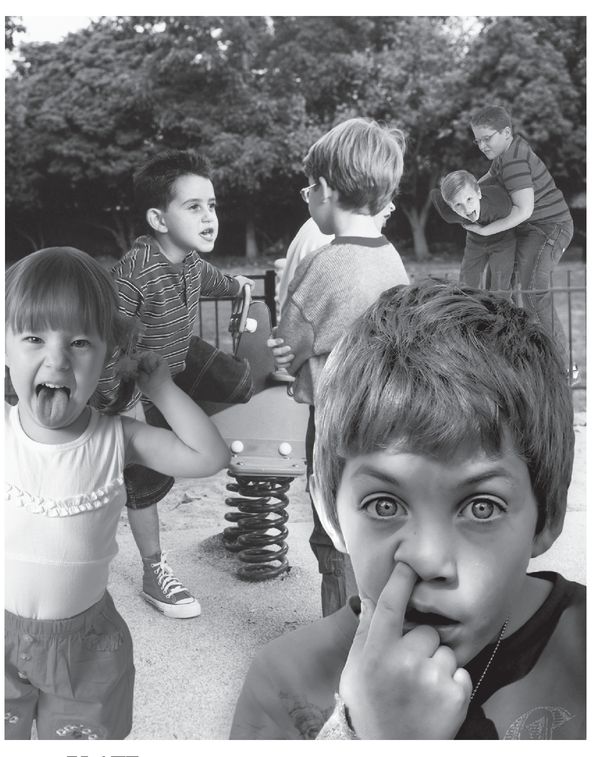

As long as a person is a child, he cannot own property, conduct business, have a real job, or do anything of actual importance. There’s a good reason for this: Children are loud, stupid, lazy, and ugly (

see plate 2

).

see plate 2

).

When they are not laughing (too loud and for no reason), they are screaming (too loud and for no reason). And when they’re not doing either of those things, they’re whining (too loud and for no reason). I would say they’re like monkeys, but monkeys are cute.

I am reminded of a winter afternoon several years ago. Setting: a shadow-filled living room, illuminated by warm lamplight and the flickering of the television set. I was sitting on the floor, playing gin rummy with my mother (and letting her win, naturally). My dog Lollipop was curled up behind me, acting as a natural backrest. My favorite movie,

The Third Man

, was on TV. The Ferris wheel scene was playing, and Orson Welles was giving his lovely speech in which he compares all the useless people on the ground to “dots”—and wonders if anyone would really care if one of those dots stopped moving.

The Third Man

, was on TV. The Ferris wheel scene was playing, and Orson Welles was giving his lovely speech in which he compares all the useless people on the ground to “dots”—and wonders if anyone would really care if one of those dots stopped moving.

All was perfect . . . except, of course, for my father. “Daddy”

6

was sitting in his armchair, impatiently rattling the magazine he was reading, crossing and uncrossing his legs, breathing heavily. This is the way weak men signal that they are unhappy. He wanted to watch a political debate or a folk-music concert or a news show—something stupid—but I shrieked when he tried to change the channel.

6

was sitting in his armchair, impatiently rattling the magazine he was reading, crossing and uncrossing his legs, breathing heavily. This is the way weak men signal that they are unhappy. He wanted to watch a political debate or a folk-music concert or a news show—something stupid—but I shrieked when he tried to change the channel.

PLATE 2: Children are loud, stupid, lazy, and ugly.

My mother said, “Little Sugarplum likes this movie.”

Daddy made a particularly ugly face: “Little Sugarplum doesn’t

understand

this movie.” I thought his tone of voice was uncalled for.

understand

this movie.” I thought his tone of voice was uncalled for.

After a while, Daddy started staring out the window. His face softened. A little smile played on his lips. “That’s really beautiful, man.”

7

7

When my mother asked him what was so beautiful (

man

), he pointed to a group of neighborhood children playing in the snow outside. They were engaged in all the traditional winter sports: shoving snow down each others’ shirts; shoving snow down each others’ pants; making each other eat snow.

man

), he pointed to a group of neighborhood children playing in the snow outside. They were engaged in all the traditional winter sports: shoving snow down each others’ shirts; shoving snow down each others’ pants; making each other eat snow.

Daddy was overcome by the charm of this scene. “They’re just so amazing at that age. So innocent. So . . . pure. As pure as the snow they play in.” He apparently hadn’t noticed the places where the snow was distinctly yellow.

Then he remembered I was in the room. He turned and gave me a searching look. “Oliver . . . don’t you want to go out and play with them? Make some new friends?”

Hmmm. Inside toasty and warm, with a pot of hot cocoa in easy reach? Or outside, wet and cold, catching diseases from a drippy-nosed scrum of screeching urchins?

“No, Daddy,” I said. “All the friends I want are right here.” And I gave his leg a great big hug. He winced.

But that was two years ago. Children are a problem that continues to plague us, even today.

We can all agree that children are ugly. Their heads are too big, their legs are too thin, their fingers too fat and grasping—they are a complete mess. But what’s most shocking about them is that their greatest ugliness is on the

inside

. I speak, of course, of their bigotry. I shouldn’t even have to mention this, because it is a natural extension of their stupidity. Stupid people are bigoted because they don’t know any better. I am amused when goody-goodies proclaim, from the safety of their armchairs, that children are naturally prejudice-free, that they only learn to “hate” from listening to bigoted adults. Nonsense. Tolerance is a learned trait, like riding a bike or playing the piano. Those of us who actually live among children, who see them in their natural environment, know the truth: Left to their own devices, children will gang up on and abuse anyone who is even slightly different from the norm.

inside

. I speak, of course, of their bigotry. I shouldn’t even have to mention this, because it is a natural extension of their stupidity. Stupid people are bigoted because they don’t know any better. I am amused when goody-goodies proclaim, from the safety of their armchairs, that children are naturally prejudice-free, that they only learn to “hate” from listening to bigoted adults. Nonsense. Tolerance is a learned trait, like riding a bike or playing the piano. Those of us who actually live among children, who see them in their natural environment, know the truth: Left to their own devices, children will gang up on and abuse anyone who is even slightly different from the norm.

I happen to be slightly different from the norm.

Which explains why at this very moment, today, at two minutes after two in the afternoon, Jordie Moscowitz is blocking my path in the hallway.

“Excuse me, please,” I say, meek as a mouse.

Jordie laughs.

8

He puts a hand on my chest. “I’d get out of your way, Chubby, but I don’t think the hallway’s wide enough for me to get past you!”

8

He puts a hand on my chest. “I’d get out of your way, Chubby, but I don’t think the hallway’s wide enough for me to get past you!”

He says this very loudly, turning his head so a group of girls by the lockers can hear him. His mane of oily black curls jiggles around his greasy face. His mouth cracks in a crooked leer, exposing braces still coated with the scrambled eggs he had for breakfast. The girls giggle.

9

9

Encouraged, Jordie opens his mouth to make another joke . . . and then stops. His face goes slack. He suddenly looks tired, puzzled. Then his puzzlement turns to horror as a greasy fart

burps

out of the back of his jeans and fills the entire hallway with a smell like burning tennis shoes.

burps

out of the back of his jeans and fills the entire hallway with a smell like burning tennis shoes.

The girls shriek with laughter

10

and run screaming down the hall. Jordie watches them go, pathetically. Then he rubs his neck and walks away.

10

and run screaming down the hall. Jordie watches them go, pathetically. Then he rubs his neck and walks away.

Jordie is new to this school—he only transferred in at the beginning of the semester. Otherwise he wouldn’t have tried to pick on me. The other boys (and some of the bigger girls) learned a long time ago not to bully me, or else they’d end up feeling tired, weak, and thirsty. Even if they don’t

know,

they know it, they know it. Experience has trained them. The little reptile brains inside their heads tell them, “Leave this one alone.” So they do.

know,

they know it, they know it. Experience has trained them. The little reptile brains inside their heads tell them, “Leave this one alone.” So they do.

Two forces make this possible:

1.

LAZOPRIL

: A chemical I invented with my first home chemistry set.

11

It completely saps the hostility from anyone exposed to it and makes them feel like doing nothing more violent than taking a nap. Side effects include sudden intense flatulence (what scientists call farts) and roughly a three-month delay in the onset of puberty. That is to say—every time you’re dosed, you put off your growth spurt by three months. I used to mix this stuff up without wearing gloves, which probably explains why my private parts are still as bare as a freshly plucked chicken.

LAZOPRIL

: A chemical I invented with my first home chemistry set.

11

It completely saps the hostility from anyone exposed to it and makes them feel like doing nothing more violent than taking a nap. Side effects include sudden intense flatulence (what scientists call farts) and roughly a three-month delay in the onset of puberty. That is to say—every time you’re dosed, you put off your growth spurt by three months. I used to mix this stuff up without wearing gloves, which probably explains why my private parts are still as bare as a freshly plucked chicken.

2.

PISTOL, BARDOLPH, AND NYM

: My bodyguards. Not their real names, of course; these are code names I picked from a Shakespeare play I used to like.

PISTOL, BARDOLPH, AND NYM

: My bodyguards. Not their real names, of course; these are code names I picked from a Shakespeare play I used to like.

It’s their job to shoot a mini-dart full of Lazopril into the neck of anyone who tries to mess with me. They do other chores for me as well—like slipping the doctored pack of cigarettes into Moorhead’s pocket, or printing up photographs from the two thousand hidden cameras I have scattered around the school

12

and putting them in my locker. I give them orders through the transmitter implanted in my lower jaw. I just

say

I want something to happen and it

happens

. It’s like magic but much more expensive.

12

and putting them in my locker. I give them orders through the transmitter implanted in my lower jaw. I just

say

I want something to happen and it

happens

. It’s like magic but much more expensive.

Obviously, there’s more than three of them. There’s a Pistol, Bardolph, and Nym who guard me when I’m at school; then there’s a Pistol, Bardolph, and Nym who guard me after school. An entirely different trio is on duty when I sleep at night.

One of my corporations does all the hiring. I don’t even know which of the people who surround me are my bodyguards; it’s safer that way. If I’m attacked, I don’t want to tip off my assailant by looking around for my bodyguards—which I would invariably do if I knew who my bodyguards were.

I do have my suspicions, however. One of my protectors is probably the heavily muscled Chinese exchange student who happens to be in all my classes. Nobody knows his name, he doesn’t seem to speak English, and he shaves twice a day. And I’m curious about the new librarian who has a Marine Corps tattoo on her ankle.

They don’t know I’m their employer. They just know that someone is paying them—and paying them very well—to protect the good-looking, slightly pudgy child at Gale Sayers Middle School and to do whatever he asks.

They’re the only reason I can walk unmolested through the school hallways, among the throngs of thimble-brains and savages who call themselves my classmates. They’re the reason no one even looks at me as I open my locker, even though—not three feet away—a gang of boys is giving Barry Huss, the shortest boy in school,

13

an atomic wedgie.

13

an atomic wedgie.

And these are the creatures my loving father, dear old Daddy, wants me to be friends with. Daddy wants me to be popular. To play team sports with these dimwits. To invite them over for sleepovers.

I’d rather have a sleepover with a flea-filled rabbit carcass.

Chapter 3:

I AM INCONVENIENCED

They say that men inherit their brains from their mothers. This is false. My mother is a shapeless, witless mass of mousy hair, belly fat, and boobs. Don’t get me wrong, I am very fond of her. (Do I love her? Am I capable of love? A question even I can’t answer.) She is very useful for making grilled-cheese sandwiches and tucking me into bed. I like to make her smile, and I try to do that a lot.

Does that detract from my evil? No. Even Vlad the Impaler had a mother. My fondness for “Mom” (she likes to be called that) serves as a nice counterpoint to the general rottenness of my character.

14

14

I’m heading home on the school bus now, which means Mom is currently in the kitchen making me a grilled cheese with pickle chips.

The hot sandwich that greets me when I get home is perhaps the highlight of my day. It’s “A Small, Good Thing.”

15

It’s also, unfortunately, very fattening, and one of the reasons that, although I am very, very handsome, I am slightly over-round.

15

It’s also, unfortunately, very fattening, and one of the reasons that, although I am very, very handsome, I am slightly over-round.

The bus ride home is a comforting prelude to that melted-cheese nirvana, with a soothing sound track that remains reliably the same every day: My fellow students shriek and gabble like baboons; Tippy, the stubble-faced bus driver grunts, “Knock it off,” every thirty seconds; the helicopter thrums rhythmically overhead.

Other books

Sea of Slaughter by Farley Mowat

Hamsikker 2 by Russ Watts

La Fleur Rouge The Red Flower by Ruthe Ogilvie

Sex and the City by Candace Bushnell

Monkey Business by Leslie Margolis

Zodiac Station by Tom Harper

Bet in the Dark by Higginson, Rachel

Snowblind by McBride, Michael

Claimed by a Scottish Lord by Melody Thomas

Some Like It Perfect (A Temporary Engagement) by Bryce, Megan