I Am China (27 page)

Authors: Xiaolu Guo

Are you a fly, or a butterfly? A fly likes rotten substances, but a butterfly prefers flowers. You say politics are rotten; you say art lives outside the rotten political sphere. Your antenna is drawn to something beyond the stench of politics. Maybe you are right in your own way. You’ll have to convince me

.

Iona finishes translating the diary entry and finds herself searching for insects on her geranium plants by the kitchen window. There is neither fly nor butterfly on her small red flowers. Instead, a sharp ringing pierces her ears. She feels a slight cramp in her head. The sounds from the street below, the all-day buzz of Chapel Market, are echoing in the chill gloom of a wet London evening.

What a peculiar thing to translate, she murmurs to herself. What’s the meaning of these strange diary fragments? Are those lonely words supposed to be Jian’s expressions of love to Mu? Or is it just me over-interpreting?

Would they still think of themselves as lovers? Where are they now? Do they still deny their love? Or have they become the tragic spirit of the Butterfly Lovers of the ancient Chinese legend? Jian and Mu have now transformed into Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai, the two star-crossed lovers of the 2,000-year-old myth.

Then Iona remembers her time in Beijing, and the Chinese boy she met in the foreign students’ club, who had desired her and sent her a poorly written English love letter, quoting lengthy lines from traditional Beijing operas, lines like “you are the falling blossoms obscuring the moon.” To a Western woman, his passion appeared naive. But at the same time he was so constrained and shy in the daylight, like a bat shrinking from the light. A young man totally of the head, not of the body. A young man very different from the Western ones she had met before. When she left China and returned to college in London, she still didn’t understand that Chinese boy’s protestations of love and, not knowing quite how to respond, she never replied to the letter.

But Jian isn’t like that, in Iona’s head at least. Or

wasn’t

like that. But maybe that’s because she has been allowed inside, into this private place, his journal. Jian is an angry monk. A hungry beggar with a knife, maybe holding it to his own chest. Ready to strike, with a single cut, and split everything in two. Maybe that’s how he played the guitar, or gave out one of these cries—a bit theatrical, but haunted at the same time.

The street lamp gleams in her room. Iona sees herself drawn to the light like a moth. Like she is drawn to those men-boys that she has known, picked up in pubs or on the Internet, and then used. What would she have done with Jian, if she were Mu? She writes his name with a ballpoint pen: .

.

Under the acid-green light, the characters seem to shimmer and move. They are etched and yet alive-seeming. Maybe it’s just her stiff, unpractised Chinese writing. She tries to imitate his writing style. His

hand, there, on top of her paper. Her mind mingles with his image and seems to touch him, maybe, with these signs, half-pictures, half-words. Did he carry this image inside his head while he lived outside of China, like an inner stamp?

inside his head while he lived outside of China, like an inner stamp?

And now she writes Mu’s name: .

.

It looks more stable to her. The strokes are like arms reaching down, wanting to embrace someone.

It’s all too much, Iona thinks. Her own life has been totally consumed. Still, there is something ungraspable about her anti-heroes, especially Jian, that inspires in her such a rampant curiosity and longing to know more. Iona almost feels that she needs to find Jian, to talk to him. She needs her Jian. She needs to think of his skin, his habits, his way of walking, his way of talking, laughing, singing and sleeping.

8

PARIS, JUNE 2012

Standing in front of a Turkish grocery. Suddenly lost the sense of where I was. I felt like I was Comrade Krymov in

Life and Fate

being put in a solitary cell and losing all sense of my humanity. He was no longer Krymov and his soul was no longer corresponding with his body. “I need a piss, open the door!” I heard myself shouting, “Open the door! And I will remain pure to my belief!” Then the door opened, I ran out, and some rude impatient shoulders pushed and cursed me in French, and suddenly I realised I was in a queue in front of the grocery. Everyone stared at me in disgust. In embarrassment I bought two apples. Two polished waxy shiny green globes: immaculate as plastic. “One-fifty, please.” The shopkeeper flapped his eyes up like a dead fish. One euro and fifty cents for two plastic apples I didn’t even want to buy.. I bit into one of the vitamin bundles anyway, right through the plastic leather jacket. Fuck me. It was absolutely tasteless. Eating a lump of cardboard

.

Rue Saint-Denis. Jian has wasted hours on the pavement, up and down, absent-mindedly looking at the glitzy shops, the beautifully lit cafes and occasional prostitutes standing about in their fur coats. He catches sight of a Chinese woman. She is probably forty-something, not young for someone who does this kind of job. Her red cheek suggests that she might have left her field just a few months ago, taken an illegal boat, a train, a coach and got herself here. Despite her fishnet tights and her fake leather coat, she reminds Jian of his mother. His mother, with her dark brown eyes, her lips full of unspoken words. He was four when his mother died. And her image remains forever young in his blurred memory.

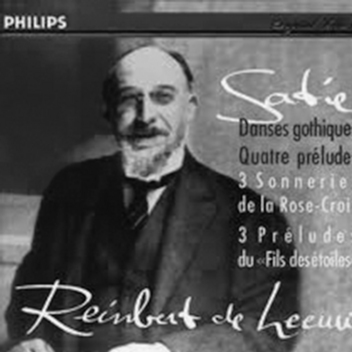

As Jian zooms up and down rue Saint-Denis, he decides to go into a record shop to find out what the CD covers of Erik Satie recordings are like in this country. In fact, he’s after a cover of the recording his mother had. Satie was the composer who indirectly killed her. He walks straight to the classical piano section and in no time finds a Satie CD. The cover design is not fashionable; he recognises the same smiley photo of the bearded man wearing the same suit he knows from a Chinese cassette, an image he remembers from his childhood.

It looks neither provocative nor decadent—how could anyone imagine that in a faraway country a mother would be classified as an enemy of the state for listening to this?

In the midst of loud pop music blaring across the shop floor, he slots the CD into a test-listening machine. Instantly a flow of melancholy piano notes seep into his ears. It’s his mother’s favourite, Gnossienne No. 4. So familiar, and deeply sad. Now Jian’s stomach begins to ache. His guts knot together each time his mind fills with heavy thoughts.

He hangs up the headphones. With the pain still in his stomach, he takes the CD to the counter.

“Do you like Satie?” the cashier asks.

“Yes,” Jian answers and pays. “But actually it’s for my mother.”

“That’s nice. Hope she enjoys it.”

A kind man, a regular nice guy, just like those innocent people who never stop to imagine that shit can fall from the sky in an instant, as they walk down the street. Jian murmurs to himself, and puts Satie in his green army bag.

9

PARIS, JUNE 2012

Marie, an old French prostitute, looks about fifty, or perhaps fifty-eight or sixty-two. She refuses to say. Whatever her age, she looks worn and drawn. One can’t help but stare at her thickly powdered face, and the eyes, like those of a silent-movie actor, heavily outlined and glimmering up from a soup of dusty make-up. What a mouth! A labouring mouth. A hard-working mouth. How many men has that mouth taken? It must have been young once, a flower, an animated jewel. Marie! As her image starts to blur in Jian’s head, he enters a Wenzhou restaurant in rue de Belleville. He is hungry, despite being unable to remove the image of that twilight creature from his mind. As he eats his pork dumpling soup, his stomach feels less miserable and those images return: Marie’s leopard-skin skirt, the intricate lace around her neck, her breasts like semi-sunken ships but surprisingly white and soft beneath her black nylon dress. This is the first European woman he has slept with. It felt more like sleeping with a mother than a girlfriend.

People come into Jian’s life the way maple leaves blow down the streets of Paris. It seems so random and futureless. He met Marie about two weeks ago, in the street where she works. The negotiation was fast. She asked for three hundred euros; he shook his head and said he couldn’t afford even half of that. They settled on eighty. They went to a nearby hotel room. The room was so small that it could only fit the single bed. When they were inside, she stripped off her clothes right away. Jian felt awkward. She wore a bodysuit, a sort of body-shaping corset with wires to lift her breasts. Jian still remembers the red mark the wire made under her chest. He didn’t ask how painful or constrained it felt in that costume. When she removed it and emerged from her

cage, her sunken bottom looked like a large deformed pear. She told Jian she had been working the area for the last two decades. And before that she was in Marseilles—she used to hang out with the sailors. She said she would carry on working until the day she couldn’t get up or didn’t have the strength to open her legs any more. “

C’est vrai

, Jian, sometimes my legs are too sore to open,” she said. “And my muscles around my crotch are aching. I need to take a hot bath three times a day!” She then laughed loudly; exactly like the big woman in that Italian film,

Mama Roma

, which Jian had watched in college. Laughing so that every part of her body shook, even her red curly hair, shaking as if electrocuted. Her laugh was coarse and threatening. It made Jian lose confidence. But he didn’t dislike her. An old female lion, he thought to himself. But after that afternoon, strangely, each time Jian walked up and down the street where he had met her, she wasn’t to be found.