"I Heard You Paint Houses": Frank "The Irishman" Sheeran & Closing the Case on Jimmy Hoffa (26 page)

Authors: Charles Brandt

Tags: #Organized Crime, #Hoffa; James R, #Mafia, #Social Science, #Teamsters, #Gangsters, #True Crime, #Mafia - United States, #Sheeran; Frank, #General, #United States, #Criminals & Outlaws, #Labor, #Gangsters - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Teamsters - United States, #Fiction, #Business & Economics, #Criminology

The Test Fleet charges involved putting a car hauling company in the names of the wives of Jimmy Hoffa and the late Owen Bert Brennan. It involved activity that had ended five years earlier. It involved activity that had been thoroughly investigated by the McClellan Committee and the Justice Department. In his opening statement to the jury, prosecutor Charlie Shaffer said that Test Fleet was set up as part of “a long-range plan, whereby Hoffa would be continuously paid off by the employer.” The government’s theory hinged on the fact that the Test Fleet enterprise was created following a strike that Hoffa had settled favorably for the employer with whom Test Fleet was to then do business.

Hoffa’s defense was that his lawyers had advised Brennan, Hoffa, and their wives that it was legal for their wives to own the company, and that once the McClellan Committee challenged its legality, his wife and Brennan’s wife withdrew from Test Fleet. Jimmy Hoffa’s lawyers were ready to testify on his behalf and confirm his version of their legal advice originally given in 1948.

The setting up of Test Fleet occurred ten days after the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act, and the lawyers were interpreting a law that had no case precedents on which to base a legal opinion. Furthermore, Hoffa was prepared to prove that the strike he had settled was an illegal strike by rebels and that he had settled it with the employer to avoid what Hoffa called a “very serious lawsuit” against the Teamsters by the employer.

To Hoffa, this case was the product of Bobby Kennedy’s vendetta against him, and the staleness of the information proved how desperate Kennedy’s Get Hoffa Squad was. The Get Hoffa Squad had already failed to get an indictment against him in any of the other thirteen grand juries that had been convened around the country for that purpose.

Jimmy Hoffa assembled the best legal talent he could find. His lead counsel would be Nashville’s best, Tommy Osborn, a young lawyer who had successfully argued the landmark and very complex reapportionment case before the U.S. Supreme Court that resulted in the “one-man one-vote” rule. Among other lawyers assisting in Nashville were the Teamsters’ attorney, Bill Bufalino, and Santo Trafficante and Carlos Marcello’s attorney, Frank Ragano.

The trial judge, William E. Miller, was a man well respected for his fairness and not likely to favor either side.

Jimmy Hoffa set up base at the plush Andrew Jackson Hotel, down the street from the federal courthouse. He had lawyers in court and lawyers back at the hotel as part of a legal brain trust. The lawyers in the wings acted as advisers and as researchers. In addition he had a multitude of union allies and other friends in court and at the hotel to serve the cause, including a man known as Hoffa’s “foster son,” Chuckie O’Brien, and Hoffa’s man on the pension fund, the ex-Marine Allen Dorfman. A number of the nonlegal entourage was from Nashville itself and would provide intelligence about, and insight into, the jurors during the selection process. These were the days before professional jury advisers.

Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that many of Hoffa’s supporters were there at the Andrew Jackson in Nashville to serve the causes, rather than just the singular cause.

There would be two dramas unfolding in the courtroom at the same time over the next two months. The first would be the trial itself: the calling of witnesses, the cross-examination of witnesses, the lawyer’s arguments, the objections, the motions, the trial rulings, the recesses, the side bars, and the oaths administered. But the trial, it turns out, was the B-picture. The other drama was the A-picture. It was the blatant jury tampering done all the while that a mole named Edward Grady Partin gave the Get Hoffa Squad all the details as they were unfolding. It was this jury tampering that ultimately would send Jimmy Hoffa to jail.

With a decent defense, with his defense well prepared, with his trial staff led by the respected and talented Tommy Osborn and fortified by Bill Bufalino, Frank Ragano, and yet more legal talent in court and on call, and with a fair judge, why did Jimmy Hoffa resort to cheating? Why did he turn a misdemeanor into a felony?

“

It was Jimmy’s ego. Other than assaults and that kind of thing, Jimmy didn’t have any convictions on his record for doing anything really wrong, and he didn’t even want a misdemeanor. He wanted a clean record. He didn’t want Bobby Kennedy causing him to have a record that involved a real crime.

You see, you’ve got to keep in mind that when Bobby Kennedy came in as attorney general, the FBI was still basically ignoring so-called organized crime. Don’t forget, when I first got involved with the people downtown before the Apalachin meeting I didn’t even know the extent of what I was getting involved in. For years and years since Prohibition ended, the only thing that the so-called mobsters had to contend with was the local cops, and a lot of them were on the pad. We never gave a thought to the FBI when I hung around Skinny Razor’s.

Then came Apalachin and the McClellan hearings, and the federal government started getting on people’s backs. Then Bobby Kennedy gets in and a bad dream turns into everybody’s worst nightmare. All of a sudden everybody that’s going along minding their own store starts getting indicted. People are actually going to jail. People are getting deported. It was tense.

Now in that Nashville trial on the Test Fleet case at the end of 1962, Jimmy’s taking a stand against Bobby, in what was shaping up like a major war ever since Bobby got in as attorney general.

”

On February 22, 1961, two days after being sworn in as attorney general, Bobby Kennedy had convinced all twenty-seven agencies of the federal government, including the IRS, to begin pooling all their information on the nation’s gangsters and organized crime.

During the months preceding the Test Fleet trial the commissioner of the IRS wrote: “The Attorney General has requested the Service to give top priority to the investigation of the tax affairs of major racketeers.” These racketeers were named and they would receive a “saturation-type investigation.” The commissioner made it clear that the gloves were off: “Full use will be made of available electronic equipment and other technical aids.”

Johnny Roselli was one of the IRS’s first targets. He lived the glamorous life in Hollywood and Las Vegas, yet he had no job nor any visible means of support. Under prior attorneys general it had never occurred to him that he was vulnerable to the government. Roselli told the brother of the former mayor of Los Angeles: “They are looking into me all the time—and threatening people and looking for enemies and looking for friends.” What made Roselli even angrier was that he suspected that Bobby Kennedy knew that Roselli was allied with the CIA in its operations against Castro. Roselli was later quoted as saying, “Here I am helping the government, helping the country, and that little son of a bitch is breaking my balls.”

Around the same time, the IRS assessed Carlos Marcello $835,000 in back taxes and penalties. At that time Marcello was still fighting deportation and was under indictment for perjury and for falsifying his birth certificate. Russell Bufalino was also fighting deportation.

Prior to the Nashville trial Bobby Kennedy had been traveling around the country personally, like a general going to his troops, urging his department to focus on organized crime. He made a list of organized crime targets for the FBI and Justice Department to concentrate on. He expanded that list continually. He went to Congress and got laws passed to make it easier for the FBI to bug these targets and to use wiretaps in court. He got laws passed allowing him to more freely give immunity to cooperating witnesses.

Jury selection began in Test Fleet on the second day of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Bobby Kennedy was not in Nashville; he was needed at his brother’s side as Jack Kennedy faced down Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and ordered that all offensive nuclear weapons that were on their way in Soviet ships to Cuba be rerouted back to the Soviet Union or the U.S. Navy would open fire. The world was at the brink of nuclear war.

As Walter Sheridan wrote, “I went to sleep in the early morning hours thinking about the very real threat of nuclear war and the possibility that Jimmy Hoffa and I would end up very dead together in Nashville.”

Instead, Walter Sheridan awoke the next day to his first instance of jury tampering. An insurance broker in the panel reported to Judge Miller that a neighbor of his had met with him over the weekend and offered him $10,000 in hundred-dollar bills to vote for acquittal should he be accepted on the jury. Hoffa’s selection of the insurance broker made sense, because insurance men—being in a business that is ultra-suspicious about being ripped off and victimized by criminal fraud—are ordinarily considered death to criminal defense attorneys. They are normally struck before they get a chance to warm the seat. Surely, the government wouldn’t strike the insurance man from the jury if he were selected from the panel.

The prospective juror was excused by Judge Miller after the judge forced the insurance broker to reveal his neighbor’s name.

It was then revealed by a number of the prospective jurors that a man who identified himself as a reporter for the

Nashville Banner

named Allen had called them to find out their views on Jimmy Hoffa. There was no reporter on the

Nashville Banner

named Allen. Someone was illegally prying into some of the jurors’ minds in search of jurors who might favor their side of the case. All of those tainted prospective jurors were dismissed.

After the jury had been selected and the trial had begun, Edward Grady Partin reported to Walter Sheridan that an attempt was going to be made by the president of a Nashville Teamsters local to bribe the wife of a Tennessee State Highway Patrol trooper. The wife was seated on the jury. Sheridan checked the data on the jurors and found among them the wife of a trooper. Agents followed the Teamsters official to a deserted road where the state trooper was waiting in his patrol car. The agents watched the two men sit in the trooper’s patrol car and talk.

With this information in hand, but without revealing the source of the tip, the government prosecutors asked the judge to remove the trooper’s wife from the jury, and Judge Miller held a hearing on the prosecution’s request. The government called the agents who had followed the Nashville Teamsters president to his rendezvous with the trooper. The agents were questioned by the judge. The government then called the Teamsters official, and the man was brought in from a side room. According to Walter Sheridan, Jimmy Hoffa flashed the man the five-finger sign, and the official took the Fifth Amendment. Next, the State Highway Patrol trooper was brought into the courtroom. After first denying everything, the trooper admitted, under questioning by Judge Miller, that the Teamsters official had offered him a deal of promotion and advancement with the State Highway Patrol in exchange for an undisclosed favor. The trooper claimed that the Teamsters official never explained to him what that future favor might be.

Judge Miller excused the wife of the trooper and replaced her with an alternate. At her home that night the tearful woman told reporters she had no idea why she had been excused.

Speaking for Tommy Osborn and Frank Ragano and the rest of the team, Attorney Bill Bufalino said, “There was no fix. And if there was, it came directly out of Bobby Kennedy’s office.”

Young attorney Tommy Osborn was in a different sort of case than the one in which he argued about reapportionment before the U.S. Supreme Court. That case had already put him in line to be the next president of the Nashville Bar Association and had helped him land the Hoffa case. The Hoffa case could best establish a national career if he got Jimmy off, and at the same time it was the case that could wreck his career if he became a part of the culture to which he was being exposed.

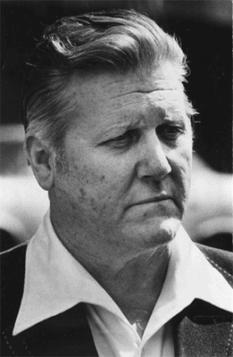

Photo Insert

Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran, circa 1970.

Courtesy of Frank Sheeran