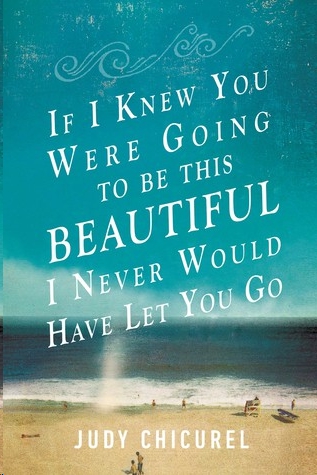

If I Knew You Were Going to Be This Beautiful, I Never Would Have Let You Go

Read If I Knew You Were Going to Be This Beautiful, I Never Would Have Let You Go Online

Authors: Judy Chicurel

G. P. Putnam’s Sons

Publishers Since 1838

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA • Canada • UK • Ireland • Australia • New Zealand • India • South Africa • China

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2014 by Judy Chicurel

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chicurel, Judy.

If I Knew You Were Going to Be This Beautiful, I Never Would Have Let You Go / Judy Chicurel.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-698-13864-3

I. Title.

PS3603.H5454I37 2014 2013051041

813'.6—dc23

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

For David.

And for my father, Michael (1919–2005), who always believed.

THREE • sex and drugs and rock ’n’ roll

FOUR • adventures in zombie land

FIVE • my country right or wrong

SIX • the fourth feeney sister

TEN • for catholic girls who have considered going to hell when the guilt was not enough

THIRTEEN • the feeney sisters forever

FOURTEEN • those girls from the dunes

FIFTEEN • conversations with my father

SIXTEEN • death to the working class

EIGHTEEN • if i knew you were going to be this beautiful, i never would have let you go

summer wind

S

o she says to me, ‘Young man, you got maniacs hanging around your store,’ and I tell her, ‘You’re right, lady, you’re a hundred percent right. I got maniacs outside my store, I got them inside my store, I got maniacs on the roof,’ I tell her.”

Desi flicked a length of ash into the ashtray we were sharing. The end of his cigar was slick with saliva. He shifted it to the side of his mouth and continued. “What am I gonna do, argue with her? Kill her? I mean, please, some of these people should maybe look in their own backyards before they come around here making comments. There’s an old Italian saying, ‘Don’t spit up in the air, because it’s liable to come back down and hit you in the face.’”

“I have no idea what that means,” I said.

“It means what it means, man,” Mitch called from the other end of the counter. “Everybody’s everything. Can you dig it?” He had a six-pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon under the arm with the rainbow tattoo and was taking a Camel non-filter from a freshly opened pack he’d just purchased. He tapped his cane twice against the counter and then winked at me before hobbling out the door. Mitch lived at the opposite end of Comanche Street, in one of the rooms at The Starlight Hotel that looked

out over the ocean and smelled of mildew and seaweed. This was the third six-pack of the day he’d bought at Eddy’s; he had to make separate trips because he could only carry one at a time. It was close to the end of the month, when his disability check ran out, which was why he was buying six-packs instead of sitting on the corner barstool by the jukebox in the hotel lounge.

Desi shook his head, mopping up a puddle of liquid on the counter. “Yeah, yeah, just ask Peg Leg Pete over there,” he muttered as the door closed behind Mitch.

“Don’t call him that, man,” I said. “I thought you liked him. I thought you were friends.” I felt a vague panic that this might not be so.

“Hey, hey, did I say I didn’t like the guy? I love the guy,” Desi said, wringing out the rag, running it under the faucet behind the counter. “But he’s not the only one sacrificed for his country. A lost leg is not an excuse for a lost life. And besides, he only lost half a leg.”

“Desi, Jesus—”

“Don’t ‘Jesus’ me, what are we, in church? And what are you, his mother? Half a leg, no leg, whatever, he don’t need you to defend him. He can take care of himself.” He shook his head. “You kids, you think you know everything.”

“I don’t think I know everything,” I said wearily. Most of the time, I didn’t think I knew anything.

“Yeah, well, you,” Desi said, moving down the counter to the cash register to ring up Mr. Meaney’s

Daily News.

“You’re different from the other kids around here. You want my advice? Get out of Dodge. Now. Pronto.” My stomach winced. I was glad no one else was around to hear him; Mr. Meaney didn’t count. I’d been hanging around Comanche Street for three years and there were still times when it felt like I was watching a movie starring everyone I knew in the world, except me. The feeling would come up on me even when I was surrounded by a million people: in school, on the beach, sitting at the counter in Eddy’s.

Desi owned Eddy’s, the candy store on the corner of Comanche Street and Lighthouse Avenue in the Trunk end of Elephant Beach. The original Eddy had long since retired and moved to Florida, but Desi wouldn’t change the name. “Believe me, it’s not worth the trouble,” he said. “Guy was here, what, twenty-five years? I pay for the sign, I change the lettering on the window, and then what? People are still gonna call it Eddy’s.” He was right. They did.

Sometimes in February, I’d be sitting in Earth Science class or World History, and outside the windows, frozen snow would be bordering the sidewalk and the sky would be gunmetal gray and I’d start thinking about having a chocolate egg cream at Eddy’s, and suddenly summer didn’t feel so far away. If I thought hard enough, I could taste the edge of the chocolate syrup at the back of my throat and it would make me homesick for sitting at the counter, drinking an egg cream and smoking a cigarette underneath the creaky ceiling fan that never did much except push the stillborn air back and forth, while everyone was hanging out by the magazine racks if the cops were patrolling Comanche Street, or sitting on the garbage cans on the side of the store where, when it was hot enough, you could smell the pavement melting. Sometimes Desi’s wife, Angie, would open the side door and start sweeping people away, saying, “Look at youse, loafing, what would your mother say, she saw you sitting on a trash can in the middle of the day?” And Billy Mackey or someone would say, “She’d say, ‘Where do you think you are, Eddy’s?’” Then everyone would laugh and Angie would chase whoever said it with the broom, sometimes down to the end of the block, right up to the edge of the ocean.

Eddy’s was open only in summer, from Memorial Day to Labor Day, sometimes until the end of September if the weather stayed warm. Desi and Angie and their kids, Gina and Vinny, moved down from Queens to Elephant Beach and lived in the rooms over the store, where they had a faint view of the ocean. On Sundays, when Vinny or Angie worked the counter, Desi would walk down to Comanche Street beach and put up a

red, white and green umbrella (“the Italian flag”) and stretch out on a lounge chair, wearing huge black sunglasses, a white cotton sun hat, polka-dot bathing trunks that looked like underwear, and white tennis shoes because once he’d cut his toe on a broken shell and needed stitches. He’d lie out on that lounge chair like a king, smoking a cigar, turning up his portable radio every time a Sinatra song came on. If any of us tried talking to him, even to say hello, he’d say, “Beat it. Today I’m incognito.”

“I’ll tell you what the trouble is with you kids,” Desi said now, walking back to where I was sitting. He took my empty glass and started mixing me another egg cream. He squirted seltzer and chocolate sauce into the glass and stirred it to a frenzy. He slid it back across the counter and I tasted it and it was perfect.

“The trouble with all a youse is you don’t know how to shut up. I mean, who am I, Helen Keller? I can’t see or hear what goes on the other side of the counter? It’s sex and drugs and rock ’n’ roll all day long and mostly sex, and now it’s not just the guys talking.” His voice dropped a shocked octave lower. “It’s the girls. The

girls

. ‘So-and-so got so-and-so pregnant,’ ‘So-and-so had an abortion,’ I mean, please, what do I need to hear this for? Look at that little girl, what’s her name, the one got knocked up didn’t even finish high school, waddling in here like a pregnant duck. Nothing’s sacred,

nothing

. And then you wonder why.” Desi shook his head. “Believe me, there was just as much sex around when your mother and I were young. Thing is, we weren’t talking about it. We were doing it.”

We both looked up as the door banged open and then just as quickly banged shut. Desi shrugged.

“False alarm,” he said.

He opened the ice-cream freezer and the cold heat from the freezer melted into the air. He began scooping ice cream into a glass sundae dish, vanilla, coffee, mint chocolate chip, and then covered the ice cream with a layer of chocolate sauce, then a layer of marshmallow topping, and finally a few healthy squirts of Reddi-wip. He picked up a

spoon and casually began digging in. Angie hated that Desi could eat like that and never gain an ounce. She said that all she had to do was look at food and she gained ten pounds. Desi said she did a lot more than look, but only when Angie wasn’t around.

I glanced up at the Coca-Cola clock behind the counter, wondering where everyone was. I’d left the A&P, where I worked, at three o’clock and figured I’d hang out at Comanche Street until it was time to go home for dinner. It was one of those dirty, overcast days in early summer and no one was at any of the usual places. They were probably at somebody’s house, in Billy’s basement, or maybe at Nanny’s. I thought about calling but the taste of the egg cream, the whoosh of the overhead fan, Desi’s familiar gluttony were all reassuring. Part of me was afraid I might be missing something, but I was always afraid of missing something. We all were. That’s why we raced through family dinners, snuck out of bedroom windows, took dogs out for walks that lasted three hours, said we had school projects and had to hang out at the library until it closed at nine o’clock at night.

The way I felt now, though, unless Luke was involved, there wasn’t that much for me to miss. Part of me was hoping he’d come into Eddy’s to buy cigarettes or the latest surfing magazine. Something. I’d only seen him once since he got back from Vietnam last Sunday, right here in Eddy’s. I hadn’t been prepared, though; I hadn’t washed my hair or gotten my tan yet, and I hid in one of the phone booths in back until he left. Since the summer before tenth grade, I’d been watching Luke McCallister, from street corners, car windows, in movie theaters, where some girl would have her arm draped around his back and I’d watch that arm instead of the movie, wanting to cut it off. I’d comfort myself that she was hanging all over him, that if he’d really been into her, it would have been the other way around. Luke was three years older, his world wider than Comanche Street and the lounge at The Starlight Hotel, all the places we hung out. But I was eighteen now, almost finished with school and ready for real life. It was summer, and anything was possible.

“Mystery,” Desi said, and I jumped a little, thinking he could read my mind. That’s exactly what I was thinking about Luke, that he was more of a mystery now than before he’d left for the jungle two years ago. I looked at Desi, who was scraping the last little bits of marshmallow sauce from the sundae dish. He pointed the stem of his spoon toward me.

“You gotta have mystery, otherwise you got nothing.”

I slurped the remains of my egg cream through the straw, making it last. Then I lit a cigarette. “I still have no idea what you’re talking about,” I said. “Speaking of mysteries.”

Desi sighed. He carried the sundae dish over to the sink and rinsed it, then set it in the drain on the side. He came over to where I was sitting and put his palms flat down on the counter and stared at me, hard. “Here’s what I’m talking about,” he said. “A girl comes in here, she’s got on a nice blouse, maybe see-through, maybe she’s not wearing a bra, I don’t know. I look, I’m excited, I start imagining possibilities. But a girl comes in here topless, her jugs bouncing all over the counter? That’s it for me. I’m immediately turned off. Why? Because now I got nothing. There’s nothing left to my imagination. There’s no mystery, you see what I’m saying here?”

I rolled my eyes. “Yeah, right. Like some girl would come in here topless and sit down at the counter and you’d have no interest.” But I could see that Desi wasn’t listening. He was just standing there, leaning against the counter with this dreamy little smile on his face.

“What?” I asked finally.

“Nothing,” he said after a moment. “I was just—” He picked up his cigar from the ashtray and relit the stub. “There was this girl, see. Back in Howard Beach. Before I started going with Angie. She used to wear this sky-blue sweater when she came around the corner.” He took a long pull from the cigar. “Little teeny-tiny pearl buttons, all the way up to her neck.” Embers spilled from the cigar stub and showered the counter.

“All those buttons,” Desi said, gazing through the smoke, as if he

was watching someone walking toward him. He put the cigar back in the ashtray and sighed again. He picked up the rag and began wiping the dead embers off the counter.

“Ah, you kids,” he said. “You think you invented it. All of it! Everything. You think you invented

life

.”