If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (30 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

In due course, though, industry and retail, with their higher wages and increased social stimulation, became increasingly attractive to the kind of young men or girls who would once have thought to become servants. Mary Hunter, who started work at Cragside House in Northumberland in 1920, had an intimate insight into the dramatic decline in household service. When she joined the household as a fourteen-year-old underparlour-maid, there were twenty-four servants. When she left it, seven years later, she was one of only three staff remaining.

By modern times servants were no longer treated with the respect they’d received when they were often young members of minor branches of the master’s own family. The Victorian

cook Hannah Cullwick bitterly resented having to ask for ‘every little thing’ she needed out of the family’s locked larder: ‘it’s inconvenient – besides I think it shows so little trust & treating the servant like a child’. Mrs Beeton, on the other hand, made it quite clear that mistresses

ought

to treat servants as inferior beings: ‘a lady should never allow herself to forget the important duty of watching over the moral and physical welfare of those beneath her roof’.

So, in the living rooms of a house, orders were given and received. The morning room, however, was the place particularly used for chastisement or praise. Here servants were interviewed for a position, and givings-of-notice and sackings took place. It’s a room that witnessed many tears as futures were made and broken. And this was often women’s work. In her marriage, the woman was clearly supposed to be subordinate. As William Cobbett put it in 1829, a husband ‘under command’ of his wife was ‘the most contemptible of God’s creatures’ – in fact, he might as well kill himself. A wife, though, had the duty to command the household’s servants. Even the put-upon fifteen-year-old addressed in

Le Ménagier de Paris

had this responsibility: ‘you must be mistress of the house, giver of orders, inspector, ruler, and sovereign administrator over the servants … teach, reprove and punish the staff’. As Mrs Beeton put it, more than 350 years later, ‘As with the COMMANDER OF AN ARMY, or the leader of any enterprise, so it is with the mistress of the house.’

At one time the heads of the departments of a great medieval household had been men of status and dignity. The few women employed were in very lowly positions indeed. A fourteenth-century reference to a ‘servant-woman’ recommends that she be ‘kept low under the yoke of thraldom’, and be given only ‘gross meat’ to eat. Yet as household sizes declined, women took over their management. In one sense eighteenth-century housekeeping was slowly losing status and becoming quite separate from the all-important sphere of public life. ‘Female Virtues are of a

Domestic turn. The Family is the proper Province for Private Women to Shine in,’ insisted a writer in

The Spectator

. At the same time, though, to remember that women were the managers of domestic enterprises is to accord them more power and respect than many would recognise from a cursory glance at life in the Georgian age. Women had the power to hire and fire. ‘People acquire and get rid of servants just as they do Horses,’ runs one account of household management written in 1850. Women made purchasing decisions and commissioned contractors to provide cleaning or fumigation services (such as that offered by Mr Tiffin, ‘bug-destroyer to Her Majesty’). A slapdash housewife might be duped into significant loss of cash or face by duplicitous servants: ‘merits greatly exaggerated – defects studiously concealed – ages falsified by the Servants themselves’.

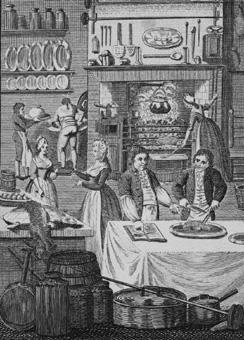

Munificent mentor or terrible tyrant? The mistress of a household might perform either role. Here a lady presents her maid with a cook book, and another servant receives instruction in the art of carving

Part of the modern misperception of housewives as tame, useless creatures stems from the idea that women were supposed to disguise their managerial status and powers. US First Lady Letitia Christian Tyler ran the president’s household almost invisibly in the 1840s: she ‘attends to and regulates all the household affairs’, but most commendably, ‘all so quietly that you can’t tell when she does it’. And despite their low profile, Letitia and her contemporaries actually had considerable authority over the behaviour of their families and dependants. ‘A clean, fresh, and well-ordered house exercises over its inmates a moral, no less than a physical influence,’ wrote one Victorian parson, ‘and has a direct tendency to make the members of the family sober, peaceable, and considerate of the feelings.’

By the nineteenth century the woman was perfectly well established as this hard-working but unruffled ‘angel in the house’, beneficent, caring, all-controlling. Her cares were to be kept to herself rather than shared with her busy, important, money-earning husband. In her drawing room, the Victorian wife was advised to talk to her husband about what she’d read in the newspaper rather than bother him with problems with the servants or the sickness of their children.

In that sense the living room was a place of repressed feelings. And so it remains today, as families struggle to answer the contentious question of who should do the housework.

29 – So Who Vacuums Your Living Room?

You will find, my young friends, that great care is necessary to clean furniture, and make it look well.

Thomas Cosnett,

The Footman’s Directory

(London, 1825)

The house-proud but depressed heroine of

The Women’s Room

(1978) has conflicting feelings about housework, enjoying it and hating it simultaneously. In her kitchen, ‘clean china pieces … gleam and reflect. The beauty was her doing.’ But she worked endlessly to achieve it: ‘cleanliness and order were her life, they had cost her everything’. She eventually presented her husband with a bill for all the services she had rendered him, and ran off to study literature at Harvard instead.

The rise of the working professional woman in the late twentieth century has brought the mistress–servant relationship back into existence in many middle-class homes after a hundred years. Both parties in the relationship are usually female now. In the Tudor royal household, though, before the fall in the status of such work, it was male scullions who swept the courtyards twice a day, removing ‘corruption and all uncleanness out of the King’s house’ because it was ‘very noisome and displeasant unto all the noblemen’. The ‘sweeping of houses and chambers ought not to be done as long as any honest man is within the precincts of the house’, advised the Tudor doctor,

Andrew Boorde, ‘for the dust doth putrify the air’.

Keeping your house clean was essential for health, but also part of presenting the right image to the world. ‘The entrance to your home … must be swept early in the morning and kept clean,’ wrote the author of the fourteenth-century

Ménagier de Paris

. The difficulty of cleaning up after a huge household was one of the things that kept great medieval noblemen on the move, trekking from residence to residence every few weeks. During the reign of Mary I, the court became trapped at Hampton Court Palace because the queen was suffering a phantom pregnancy and could not travel. While Mary endured the ‘swelling of the paps and emission of milk’, the courtiers gathered for the expected birth. The squalor grew; the garderobes overflowed into the moat. The conditions grew so foul that tension between the English courtiers and the Spanish supporters of Mary’s husband Philip reached boiling point. Philip had to threaten that the first Spaniard to draw his sword would have his right hand cut off. Cleaning could therefore be a fraught, important issue, whereas today it consumes so much less of a household’s time and energy that we tend to give it little thought.

Of course, the economics of the labour market meant that right up into the twentieth century it was simply cheaper to employ humans to do many household jobs. The Royal Society was presented with the idea of a washing machine (for ‘rinsing fine linen in a whip cord bag, fastened at one end and strained by a wheel cylinder at the other’) by Sir John Hoskins as early as 1677, but the first patents for such machines were not filed until more than a hundred years later. So those who could afford it sent their clothes out to an industrial laundry.

It was a woman, Melusina Fay Peirce, who first proposed the concept of co-operative housing in 1869, and her motivation was to abolish the burden of individual cooking, washing and sewing. Living communally should minimise ‘all the waste of ignorant and unprincipled servants and sewing women, all the

dust, steam and smell from the kitchen, and all the fatigue and worry of mind caused by the thousand details of our modern housekeeping’. Unfortunately, though, the experimental communal laundry she set up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, collapsed for want of efficiency.

When it did take off, co-operative living was inspired by convenience, not by high-minded ideas like Peirce’s. The Ansonia on Broadway became America’s most advanced ‘apartment hotel’, expensive but ultra-convenient. As well as enjoying their own flats, residents could use the swimming pool, Turkish baths, storage facilities, car-repair shop, grocery store, barber, manicure studio, safe-deposit boxes and cold-storage room for furs in the basement. They could eat in their shared dining room on the seventeenth floor, and the whole building was linked by a remarkable system of pneumatic tubes.

But living in a hotel to eliminate the housework didn’t really catch on outside the biggest and richest cities. In fact, the ‘big bold twentieth-century boarding house’ of Jazz Age New York was criticised by the

Architectural Record

as being inimical to proper family life, ‘the consummate flower of domestic irresponsibility’. If a woman wasn’t going to clean her own house, the

Record

argued, what on earth was she going to do instead? The apartment hotel was ‘the most dangerous enemy American domesticity has had to encounter’.

Few people would make such a claim today, so there must be some other reason for the inescapable fact that throughout Western society households have been shrinking, not growing, in recent centuries. Households in the West have declined from an average of 5.8 members in 1790 to the current 2.6 in America today. It’s partly because labour-saving devices have made economies of scale in cooking, washing and cleaning less and less attractive. But there’s something else to consider as well.

The Harvard legal scholar Robert C. Ellickson points to ‘transaction cost’ as an alternative explanation for these relatively

small-scale units. This is the notional cost incurred every time an extra body is added to the household, as newcomers need to invest time and effort in acquiring the knowledge that allows the organisation to run at its financial and emotional optimum. In larger groups decision-making becomes more costly and complicated. Only in times of upheaval and danger does an extended household present an advantage, hence the enormous resident entourages of medieval warlords or the kibbutzim in Israel’s early years. (The kibbutz still exists, yet, significantly for Ellickson’s argument, its members now demand less communal dining and more private space.)

And so each small household today sees to its own vacuuming or laundry or rat-catching, and men and women argue constantly about whose gender bears the heaviest burden. Maybe, as the world becomes a more hostile place with shortages of water and oil, we will return to the larger units of living favoured in dangerous medieval times. And perhaps then the basic activities of cleaning and preparing food will rise in status once again.