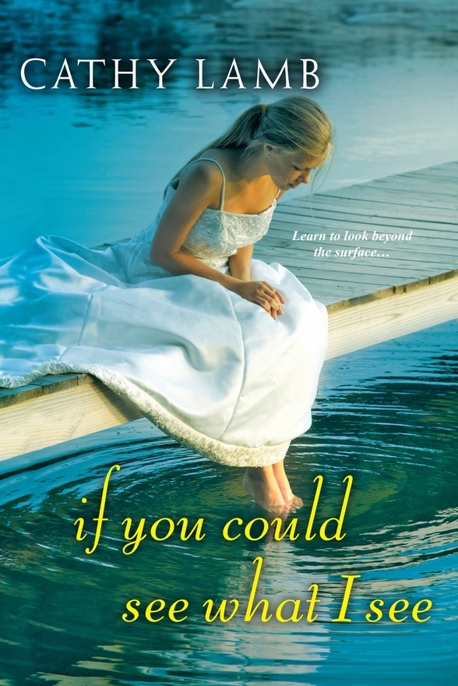

If You Could See What I See

Books by Cathy Lamb

JULIA’S CHOCOLATES

THE LAST TIME I WAS ME

HENRY’S SISTERS

SUCH A PRETTY FACE

THE FIRST DAY OF THE REST OF MY LIFE

A DIFFERENT KIND OF NORMAL

IF YOU COULD SEE WHAT I SEE

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

if you could see what

I

see

I

see

CATHY LAMB

KENSINGTON BOOKS

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

For Dr. Karen Straight, Matt Farwell,

Dave Lamb, Trevor Lockwood,

Jimmy, Wendi, and Noah Straight,

and for Marcus and Nancy Sassaman,

with love

Dave Lamb, Trevor Lockwood,

Jimmy, Wendi, and Noah Straight,

and for Marcus and Nancy Sassaman,

with love

1

B

lack.

lack.

That’s what he was wearing when it happened.

I never wear black anymore.

He ended up wearing red, too.

That’s what killed my soul.

The red.

He haunts me. He stalks me.

For over a year I have tried to outrun him.

It hasn’t worked.

My name is Meggie.

I live in a tree house.

He ended up wearing red, too.

That’s what killed my soul.

The red.

He haunts me. He stalks me.

For over a year I have tried to outrun him.

It hasn’t worked.

My name is Meggie.

I live in a tree house.

2

M

y family sells lingerie.

y family sells lingerie.

Negligees, bras, panties, thongs, bustiers, pajamas, nightgowns, and robes.

My grandma, who is in her eighties, started Lace, Satin, and Baubles when she was sixteen. She said she arrived from Ireland after sliding off the curve of a rainbow with a dancing leprechaun and flew to America on the back of an owl.

I thought that was a magical story when I was younger. When I was older I found out that she had crisscross scars from repeated whippings on her back, so the rainbow, dancing leprechaun, and flying owl part definitely dimmed.

Grandma refuses to talk about the whippings, her childhood, or her family in Ireland. “It’s over. No use whining over it. Who likes a whiner? Not me. Everyone has the crap knocked out of them in life, why blab about it? Blah blah blah. Get me a cigar, will you? No, not that one. Get one from Cuba. Red box.”

What I do know is that by the time Regan O’Rourke was sixteen she was out on her own. It was summer and she picked strawberries for money here in Oregon and unofficially started her company. The woman who owned the farm had an obsession with collecting fabrics but never sewed. In exchange for two nightgowns, she gave Grandma stacks of fabric, lace, satin, and huge jam bottles full of buttons. Grandma worked at night in her room in a weathered boarding house until the early hours and sold her nightgowns door to door so she would have money for rent and food.

Lace, Satin, and Baubles was born. Our symbol is the strawberry.

My grandma still works at the company. So do my sisters, Lacey and Tory. I am back at home in Portland after years away working as a documentary filmmaker and more than a year of wandering. You could ask me where I wandered. I would tell you, “I took a skip and a dance into hell.” It would be appropriate to say I spent the time metaphorically screaming.

My car broke down on the way back home, which pissed me off. I had bought it in Seattle, the city I flew into from the Ukraine. It was an old clunker, but still. It couldn’t go a hundred more miles? I put it in neutral and shoved it over a cliff.

I had to hitchhike. I know that hitchhiking is dangerous. What bothered me was that the dangerous part didn’t bother me at all. I was not worried about being picked up and murdered. That’s the state I’m in right now, unfortunately.

I rode with a trucker. At one point she took off her shirt and drove half-naked. She said it was a tribute to her late husband, who used to drive trucks with her. She would take off her shirt to keep him awake. I took my shirt off, too. I don’t know why. She put in a CD and we sang Elton John’s “Crocodile Rock” together six times. It was her husband’s favorite song. We cried.

When I arrived at Lace, Satin, and Baubles, my sisters each grabbed one of my elbows and hauled me upstairs to the light pink conference room. There’s a long antique table in the middle of it, a sparkling chandelier, an antique armoire, a pink fainting couch, a rolltop desk, a photo of a strawberry field, and a view of the city of Portland. Inside that room we run a company. It isn’t always pretty.

My sisters did not have pretty news for me.

Tory raised a perfectly arched black eyebrow at me, swung her leopard print designer heel, and said, “You look awful, Meggie. Ghostly, somewhat corpselike. You’re not wearing makeup, are you? You need it.”

“You don’t look

awful,

Meggie. You look like you need . . . a . . . a . . . nap.” Lacey was wearing one of our best-selling black lace negligees as a shirt. “Welcome home. I’m glad you’re here.”

awful,

Meggie. You look like you need . . . a . . . a . . . nap.” Lacey was wearing one of our best-selling black lace negligees as a shirt. “Welcome home. I’m glad you’re here.”

“Yes, welcome home, Meggie,” Tory said, her tone snappish. “Please don’t go out in those clothes. It’s bad for the company’s image. Homeless is not a style, you do know that, right?”

I was not offended. I didn’t care. I leaned back in an antique chair, stared at the ceiling, and linked my hands behind my blond, too long, frizzy curls. I needed a beer.

“ ’Bout time you got here, though.” Lacey put her leather knee-high boots flat on the ground and leaned on her elbows, her red curls tumbling forward. She has dark brown eyes, like coffee, like mine. “We’re in serious trouble and we’re going to need you to fix this immediately.”

“Yep,” Tory said, tossing her thick black hair back. “We’re almost broke.”

“What?”

I said, shocked, my chair slamming back down. “Are you kidding?”

I said, shocked, my chair slamming back down. “Are you kidding?”

“No,” Lacey said. “We are months from being out of business.”

I looked from one sister to the other, back again, then uttered aloud the only thing that made sense at that moment: “Now I really need a beer.”

I drummed my fingers against the table as my sisters launched themselves into a fiery and spear-throwing argument about why we were almost broke, which was their typical mode of communication. Verbal grenades were tossed. I interrupted the grenade tossing. “Why didn’t you tell me that the company was in so much trouble?”

“Because Grandma told us to wait until you were back in the doors here,” Lacey said. She is married with three teenagers. She says they are sucking the life out of her “through a straw and a strainer.”

“She wanted you to enjoy your strange and bizarre year away tramping around the world like a lost space alien,” Tory said, “without the full knowledge of our impending disaster.”

“She should have told me.” Fear started tingling my back. This was not good.

“It isn’t my fault the company’s taken a dive, Meggie,” Tory said. “It’s the economy. The numbers aren’t being crunched right.” She glared at Lacey, who was the chief financial officer. “The designers are evilly moody, defiant, hormonally imbalanced, won’t take direction, and won’t be creative on their own. It’s like working with temperamental one-eyed Cyclopses.”

“You’re the chief designer, Tory,” Lacey snapped.

Tory humphed, examined her nails. They were painted purple. “I

manage

the designers.”

manage

the designers.”

“You hired them,” Lacey said.

Tory rolled her eyes. Her eyes are golden, no kidding. They’re stunning. Her full name is Victoria Martinez Stefanos O’Rourke. Hispanic-Greek-Irish. My mother adopted her when she was five. Her mother was Mexican American, her father Greek American. They were killed in a car accident on the way to the beach. Tory was in the car at the time but to this day doesn’t remember anything. Her mother, Rosie, who was my mother’s best friend, was the company’s accountant.

When we were younger, before Tory’s parents were killed, Tory, Lacey, and I called each other “cousin.” I called Rosie and Dimitri Aunt Rosie and Uncle Dimitri. Tory called my mother Aunt Brianna. When she came to live with us, my mother told us we were now all sisters. I know Tory has struggled with feeling like a sister. Lacey and I have always been close, “like an Oreo cookie,” Tory says, and it made her feel “like rotten milk.”

Agewise, Tory is almost exactly in the middle of Lacey and me, with me being the youngest. She wears tight, high-end suits, dresses, skirts, and heels every day. We use her, and her style and flair for lingerie, for the media. She is currently separated from her husband, Scotty, and she is as miserable as a lost puppy.

“Working with the designers is like trying to lasso cats.” Tory mimed lassoing cats.

I tamped down my anger. “You’ve fired three designers in the last year, right?”

“I had to. It was my given duty.”

“Your

given

duty? Because?”

given

duty? Because?”

Tory glared at me. “One was a slut—”

“Why would we care if she’s a slut?” I threw my hands in the air. “It’s not our place to make judgments about our employees’ sex lives, and if she’s not boinking anyone’s husband or boyfriend here at the company, or her boss—that would be you, Tory—or her subordinates, what’s it to us?”

“She always told me about her boyfriends.”

Lacey screeched a bit between clenched teeth. “You were jealous of her.”

“If you told her she was fired for being a slut, the lawsuit against us will stretch to the North Pole,” I said.

“I didn’t

tell her

she’s a slut.”

tell her

she’s a slut.”

“In a meeting,” Lacey said, “Lorinda said you were the most monstrously difficult and snotty totty person she had ever met. I liked the words

snotty totty,

frankly. Monstrously difficult was well chosen, too.”

snotty totty,

frankly. Monstrously difficult was well chosen, too.”

“And what happened to the other designers?” I asked.

“Rebecca,” Tory snorted. “She smelled like a chicken slaughterhouse and she did not respect me or my position here—”

“She’s a designer,” I said. “She’s an artist of clothes. Designers tell you what they think. Sometimes they say it nice, sometimes they don’t.”

“Rebecca had new ideas—” Lacey said, her face flushed.

“She wanted to add all sorts of bold colors and blurred designs, like paintings, and murals.” Tory waved a hand dismissively in the air. “Who are we, Van Gogh? Ridiculous. Maybe I’ll cut off my ear and send it to her.”

“You brag so much about knowing designs, but you stifle and scare your employees,” Lacey yelled, snapping a pencil in her hands.

“I don’t stifle or scare anyone unless they’re boomeranging idiots,” Tory yelled back. “We sell tons of lingerie that I design—”

“Stop!” I shouted, slamming my hands on the table. “Stop fighting. I came home, I’m here, and I’m trying to figure out this mess. Back to the designers. Why did the third designer get fired?”

“I fired Chiara because she had a drinking problem,” Tory said, tilting her chin up, her jaw tight.

“Chiara didn’t have a drinking problem until about six months ago,” Lacey ranted, hands up in the air, her silver bracelets clinking. “She said she started shooting back vodka to be able to handle you, Tory.”

“Not true,” Tory said. “She started drinking because . . .”

“Because?” I prodded.

“Because.” Tory sat straight up. “She’s a Gemini.”

I fell back in my chair. Would I get a migraine from today? “Geminis drink more?”

“Where does it say that?” Lacey said, pushing her red curls back with both hands. “Have the stars formed a sign that says, ‘Geminis are lushes’?”

“You lack the innate spirituality needed to understand star signs,” Tory said.

“I don’t

believe

in star signs,” I said. “I believe in numbers, and what I understand is that this company is almost out of business and it has nothing to do with Geminis slamming vodka down.”

believe

in star signs,” I said. “I believe in numbers, and what I understand is that this company is almost out of business and it has nothing to do with Geminis slamming vodka down.”

“This financial screwup is no thanks to you, Queen Mommy,” Tory railed at Lacey. “Who keeps leaving me here to run carpools for cheerleading and to go to football games?”

Lacey, her face flaming said, “Don’t bring my kids into this. You never even come over to see them. You’re a lousy aunt.”

I saw Tory’s face crumble, then she put her mask back on. “As chief financial officer, Lacey, why didn’t you do something to fix this?”

“Ladies, can we refocus here?” I said, but it lacked gusto. All was lost with the “lousy aunt” comment.

“I can’t get the numbers up unless you put together products that people with brains want.” Lacey turned and grabbed a mannequin that was wearing a light blue bra and light blue panties. She charged Tory with the mannequin, as if it were a person starting a fight.

I put my hand to my forehead. Yep. Migraine.

“Look at this! Your design! The stuff you’re turning out is boring. It means nothing. It’s plain. It’s normal. We might as well call it ‘Stuff your bladder-challenged grandma will like!’ ” She took the bra off the mannequin and hurled it in Tory’s direction.

Not to be outdone, Tory, her face rigid with outrage, grabbed another mannequin, dressed in a burgundy negligee with black lace and a snap crotch, and charged back at Lacey. “Some of our stuff is plain because that’s what some of our customers want. This design, my design, is a work of lingerie art!”

I don’t think she meant to, but Tory slammed the mannequin down so hard an arm broke off.

We had two mannequins facing off in battle, wobbling back and forth. I sighed.

“Why don’t you go Botox your butt?” Lacey picked up the downed arm of Tory’s mannequin and threw it against the wall. The arm shattered, and the bang echoed through the room. “I am sick of you blaming me.”

“I’m sick of you, Lacey!” Tory detached the arm of Lacey’s mannequin in revenge, and it went flying and hit the other wall. Another shatter and bang. “Say good-bye to your arm!”

The door opened and my assistant, Abigail Chen, who moved from Vietnam when she was a little girl, changed her first name, and “became American,” said, “Ah, another fight. No blood then yet?”

I shook my head.

“Okay. Let me know. Blood stains, you know.”

“Yes, I realize that,” I said.

“But the dental plan will cover broken teeth.” Abigail raised her voice above the ruckus, the insults, and a few swear words as Lacey and Tory roared, each ripping the other arm off the opposing mannequin. “It’s good to have you home. I think the family needs you, Meggie.” She is good at sarcasm.

“I think they need me to break up the fights. Remember, it’s all fun and games until someone gets bashed in the head.” As if on cue I ducked as the head of a mannequin was knocked off and went flying across the room, missing me by inches.

Abigail raised her eyebrows at me. “Welcome home, Meggie.”

“Thank you, Abigail. Glad you haven’t quit working at the animal house.” I blocked a flying mannequin leg with my arm. “It can be dangerous here.”

She called and left a message on my cell phone. She was calling the police. She would have me arrested. I would go to jail forever. I shivered, a graphic image paralyzing my mind, then deleted it.

I’m renting a tree house. It’s circular in shape, five years old, and was built on a private acre lot off a quiet street up in the hills of Portland. There’s a long, curving driveway, and it has a city view.

It’s owned by a friend of my mother’s. Zoe wants to sell it to me. She moved to Mexico because “The men are hotter.”

Other books

Tapestry of Fear by Margaret Pemberton

Golden Boys by Sonya Hartnett

The False Martyr by H. Nathan Wilcox

Dreaming of the Billionaire by Bright, Alice

Taken by Vixen, Laura

Promised by Caragh M. O'Brien

I’m Losing You by Bruce Wagner

Passion to Protect by Colleen Thompson

Lemons 02 A Touch of Danger by Grant Fieldgrove

The House on Hancock Hill by Indra Vaughn