IGMS Issue 22 (9 page)

Authors: IGMS

Uncle Hervé never came back home.

After a few days, Aunt Albane came to our flat, tall and unbending -- but somehow walking even more slowly, even more painfully than usual. She spoke in a low voice with my parents; and they all left. When they came back, it was with a soft-spoken man who said he was a policeman, and who asked me dozens of questions about Uncle Hervé and what he'd said. He was ill at ease during the whole interview, I could tell; and when I spoke of our home, he turned away, as if I were still a child who had to be managed.

He never came back; and neither did Uncle Hervé.

Jamila wasn't surprised. "Men will be men. Always ready to do the stupidest things."

"Uncle Hervé isn't like that," I said, horrified.

"Toufiq isn't like that either," Jamila snapped. "And yet here he is, bringing us this tosh about proper women remaining inside -- about how it's all in the Qur'an, and we've been living like heathens here." She brought her dark hands together forcefully. "Sorry, Em. That idiot boy's been driving me crazy."

"Don't worry. It doesn't matter," I said. But Toufiq wasn't Uncle Hervé, who had lived there under the sea; who knew all the ways to snatch fish from shoals, all the hiding places under the rocks, the ways to forage, away from the cargo ships and super tankers that had claimed the sea's surface. Surely he wouldn't go back, just to die.

But then, if he hadn't died, what was I still doing here?

The first hint we had that something was wrong with Father was when he fainted in the kitchen. He'd never been quite himself since Uncle Hervé's departure, but I'd thought it was grief, or anger, or a mixture of both. We tiptoed around him, sister-in-law and mother and daughter; but when he swayed, and fell in the midst of a conversation with Mother on a bright Sunday afternoon, we knew it wasn't grief.

The SAMU ambulance was quick to arrive, and Mother and I rode the metro to the hospital. She was silent by my side, her head bent, her long, tapered fingers joined together in what seemed to be a prayer. She smelled of sour fear, of water imprisoned in some lake or pond, stale and unmoving. I'd have prayed, too, if I'd know which gods were mine anymore.

At the hospital, they took Mother aside to give her the diagnosis. I only caught snatches of their conversation, with words like "tumour" and "operation" wafting up to me, freezing my heart in my chest; but when Mother came to sit by my side she was as much as she'd always been, her eyes remote, the same pearly-white as dead things.

"He isn't well," she said.

"How unwell?"

"I -- I don't know. There --" She inhaled; the gills on her neck distended, sharply. "You know your father was in the sea, when he was very young."

"When he saved you."

Mother grimaced, but nodded her head in a jumble of iridescence, and went on. "He caught something then. It lay low all those years, like a slowly-festering wound. It . . . it's spread."

"Can they do anything?" I asked.

"They'll open him up and cut it out," Mother said. "But there's so much of it --" Her voice drifted away -- focused again, and her eyes shifted from dead-white to grey. "He'll be fine. You'll see." She didn't sound like she believed any of it.

It was the Dark King again, reaching out, spreading his shadow over our family, even from the past. "In the sea --"

She raised a hand. "Don't. I know what your aunt and uncle have been telling you, the wild tales they've filled your head with. It's past time for those."

"Then what time is it?" I asked, almost screaming. "You've never told me anything, anything at all!"

"Émilie." Her voice was firm. "The time for being a child is past. Now, will you be a good girl and fetch me some things from home?"

Alone at home, I crept into my parents' room, expecting at any moment that someone -- Father, Mother, Uncle Hervé -- would stop me, grab me by the shoulders and turn me around and ask me what in the name of the Abyss I thought I was doing.

But there was only silence; and the sound of my breath, stretching the gills in my neck. Carefully, I wedged myself under the bed and pulled out Father's box.

It had no lock and opened easily, as if eager to disgorge its secrets. Inside were all the papers Father had pulled out, with diagrams and crosshatched maps, and formulas that swam under my eyes. There was a diagram of the instrument, too, and meticulous explanations on its making and mass production -- talk of pheromones and mating season, and other words that made no sense.

I read a few more of the papers: the language was equally archaic, like that of old romances, and speaking of things like the spread of pollutants and the growing rate of mutations and the number of years left before the seas became unviable for plankton, for fish -- for mermen.

Aunt Albane had called them clever; but all I saw, in those words and sentences I could barely understand, were yet more explanations from a foreigner's eye, from someone who hadn't understood a thing about the sea or the blessed Abyss; of what it meant to be a merman. From someone who had married a merwoman and done his best to turn her human -- and done the same to her child in turn, telling her nothing of the past or the lost country.

At the bottom of the chest were two things: Father's armour, a green-and-grey suit cut for a much thinner man than the one he'd become over the years. It clung to my skin when I unfolded it; and the hood had a small mask inside, which released oxygen when I pressed it against my skin.

And the sword.

It sang when I lifted it -- a sound without sound that vibrated in my bones like the sea's embrace, as if I had become the instrument's resonance box myself. Slowly, carefully, I ran my fingers over the handle, seeing reflections form under my fingertips, memories of mother-of-pearl and fish-scales -- and all the while the sound grew, until it seemed to fill me from end to end.

With this, Father and his companions had sung the mermen out of the sea, and tied Mother to the shore. With this, our exile had started; and I was nothing but the product of it -- someone who would never be at ease on dry land, in choking air. I could live out the rest of my life like Mother, dwindling further and further away from the sea and what she had been, or . . .

Or, like Uncle Hervé, I could have faith in the blessed Abyss, and follow the way home.

In my mind I heard Mother's words:

the time for being a child is past.

And she was right. I had been sheltered; I had been frightened; I had been lost.

But no longer.

I thought to call Jamila, but it was past the point when she'd have understood any of it.

Instead, I dialled Aunt Albane's number -- it seemed to ring for hours while she dragged herself to the living room to pick it up. "Em?" she finally asked.

I didn't leave her time to think. "You know where he went."

"I don't approve," Aunt Albane said.

"Please."

When she didn't answer, I said, "He went home, didn't he? Back to Brittany."

There was silence on the other end of the line, and it told me all I needed to know. "You know home is here," Aunt Albane said.

"I know I should have a choice. No one gave me any."

She made a sound in her throat, like the whistle of a fish, but by then I was already hanging up.

Home. He'd gone home -- to wind and surf, to brine and fish -- to the familiar currents and the never-ending pull of the tides.

I would find him, and everything would be right again with the world.

I gathered Father's maps, my heart hammering against my chest -- and went to look up the train timetable to Brittany.

I left the small duffel bag with Father's armour and sword in a locker at the Montparnasse train station, and made my way back to the hospital with the things Mother had asked of me.

They'd moved Father into a large room where other people lay sedated, moaning quietly in their sleep. Partitions of cloth were all that gave the illusion of privacy.

I found them by the smell, which I could find even through the sour ones of sickness and rotting bodies -- a hint of sea-salt, of brine-laden wind, like a caress; like a promise, once broken, now made whole again.

Mother sat in a plastic chair, half-turned away from me. I walked noiselessly and she didn't turn when I arrived. I slid the bag down to the floor in silence, groping for words I could say -- for excuses, but there was nothing left.

She was watching Father's still form, her whole body taut with a terrible intensity. In that moment she looked like a princess from the depths, wild and terrible and elemental, with the fury of the sea in her grey gaze -- and then the moment was gone, and she was only a frail old woman in a hospital room, waiting for death's visit.

I turned, without a word, and left -- running towards my train, and the waiting sea.

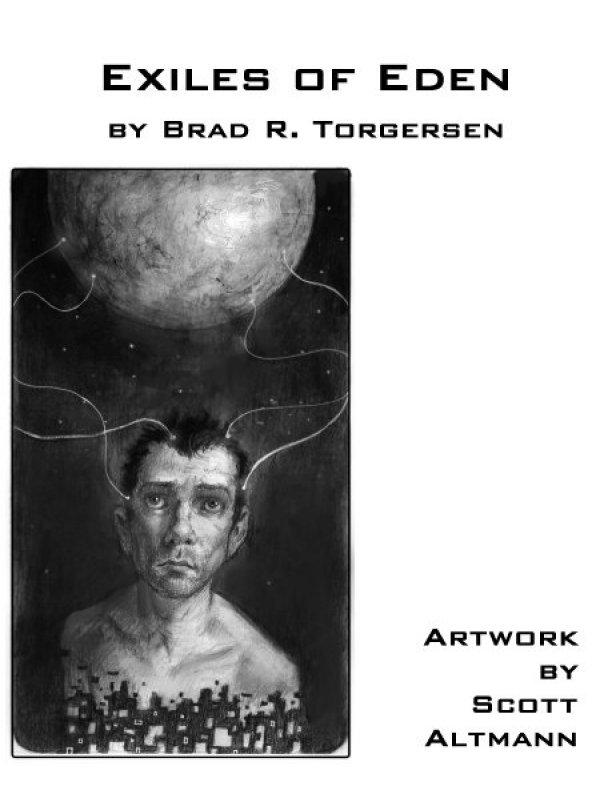

by Brad R. Torgersen

Artwork by Scott Altmann

She was gorgeous, and didn't look a day over twenty-five. Her honey-blonde hair fanned about her head as she lay beside me on the limestone sand of the beach. Two suns -- one white and the other orange -- baked our bellies. Occasionally a bubbling wave of warm seltzer water rushed in from the lifeless sea, coating us pleasantly. Her deep blue eyes blinked as I adjusted my position and gazed at her.