IGMS Issue 9

Authors: IGMS

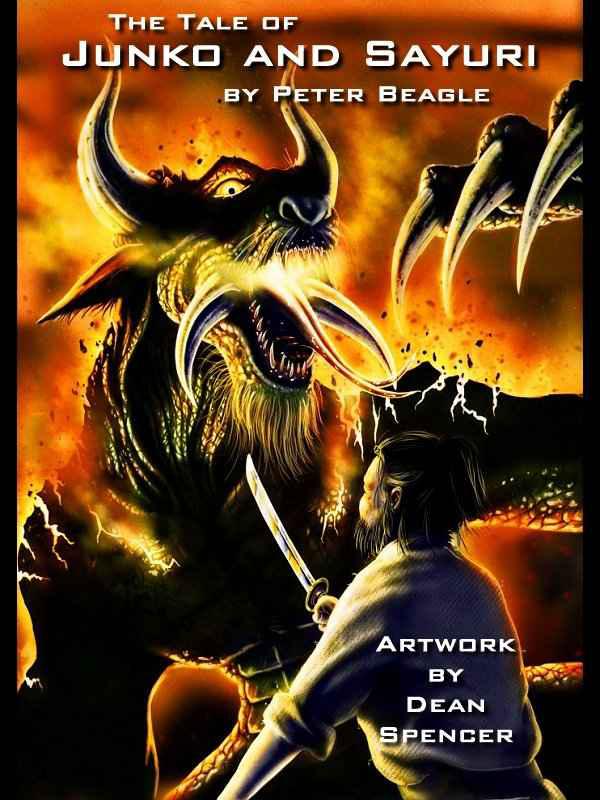

by Peter Beagle

Artwork by Dean Spencer

In Japan, very, very, long ago, when almost anybody you met on the road might turn out to be a god or a demon, there was a young man named Junko. That name can mean "genuine" in Japanese, or "pure," or "obedient," and he was all of those things then. He served the great

daimyo

Lord Kuroda, lord of much of southern Honshu, as Chief Huntsman, and was privileged to live in the lord's castle itself, rather than in any of the outer structures, the

yagura

. In addition, he was handsome and amiable, and all the ladies of the court were aware of him. But he had no notion of this, which only added to his charm. He was a very serious young man.

He was also a commoner, born of the poorest folk in a poor village, which meant that he had not the right even to a family name, nor even to be called Junko-

san

as a mark of respect. In most courts of that time, he would never have been permitted to look straight into the eyes of a samurai, let alone to live so intimately among them. But the Lord Kuroda was an unusual man, with his own sense of humor, his own ideas of what constituted a samurai, and with a doubtless lamentable tendency to treat everyone equally. This was generally blamed on his peculiar horoscope.

Now at this time, it often seemed as though half of Japan were forever at war with the other half. The mighty private armies of the

daimyos

marched and galloped up and down the land, leaving peasant villages and great fortresses alike smoldering behind them as they pleased. The

shogun

at Kyoto might well issue his edicts from time to time, but the shogunate had not then the power that it was to seize much later; so for the most part his threats went unheeded, and no peace treaty endured for long. The Lord Kuroda held himself and his own people aside from war as much as he could, believing it tedious, pointless and utterly impractical, but even he found it wise to keep an army of retainers. And the poor in other less fortunate prefectures replanted and built their houses again, and said among themselves that Buddha and the

kami --

the many gods of Shinto -- alike slept.

One cold winter, when game was particularly scarce, Junko went out hunting for his master. Friends would gladly have come with him, but everyone knew that Junko preferred to hunt alone. He was polite about it, as always, but he felt that the other courtiers made too much noise and frightened away the winter-white deer and rabbits and wild pigs that he was stalking. He himself moved as quietly -- even pulling a sledge behind him -- as any fish in a stream, or any bird in the air, and he never came home empty-handed.

On this day, as Amaterasu, the sun, was drowsing down the western sky, Junko also was starting back to the Lord Kuroda's castle. His sledge was laden with a fat stag, and a pig as well, and Junko knew that another kill would load the sledge too heavily for his strength. All the same, he could not resist loosing one last arrow at a second wild pig that had broken the ice on a frozen stream, and was greedily drinking there, ignoring everything but the water. It was too good a chance to pass up, and Junko stood very still, took a deep breath -- then let it out, just a little bit, as archers will do -- and let his arrow fly.

It may have been that his hands were cold, or that the pig moved slightly at the last moment, or even that the growing twilight deceived Junko's eye, though that seems unlikely. At all events, he missed his mark -- the arrow hissed past the pig's left ear, sending the animal off in a panicky scramble through the brush, out of sight and range in an instant -- but he hit

something.

Something at the very edge of the water gave a small, sad cry, thrashed violently in the weeds there for a moment, and then fell silent and still.

Junko frowned, annoyed with himself; he had been especially proud of the fact that he never needed more than one arrow to bring down his prey. Well, whatever little creature he had accidentally wounded, it was his duty to put it quickly out of its pain, since an honorable man should never inflict unnecessary suffering. He went forward carefully, his boots sinking into the wet earth.

He found it lying half-in, half-out of the stream: an otter, with his arrow still in his flank. It was conscious, but not trying to drag itself away -- it only looked at him out of dazed dark eyes and made no sound, not even when he knelt beside it and drew his knife to cut its throat. It looked at him -- nothing more.

"It would be such a pity to ruin such fur with blood," he thought. "Perhaps I could make a tippet out of it for my master's wife." He put the knife away slowly and lifted the otter in his arms, preparing to break its neck with one swift twist. The otter's sharp teeth could surely have taken off a finger through the heavy mittens, but it struggled not at all, though Junko could feel the captive heart beating wildly against him. When he closed his free hand on the creature's neck, the panting breath, so softly desperate, made his wrist tingle strangely.

"So beautiful," he said aloud in the darkening air. He had never had any special feeling about animals: they were good to eat or they weren't good to eat, though he did rather admire the shimmering grace of fish and the cool stare of a fox. But the otter, hurt and helpless between his hands, made him feel as though he were the one wounded, somehow. "Beautiful," he whispered again, and very carefully and slowly he began to withdraw the arrow.

When Junko arrived back at his lord's castle, it was full dark and the otter lay under his shirt, warm against his belly. He delivered his kill, to be taken off to the great kitchens, gravely accepted the thanks due him, and hurried away to the meager quarters granted him at the castle as soon as it was correct to do so. There he laid the otter on a ragged old cloak that his sister had given him when he was a boy, and knelt beside the creature to study it in lamplight. The wound was no worse than it had been, and no better, though the blood had stopped flowing. He gave the otter water in a little clay dish, but it sniffed feebly at it without drinking; when he put his hand gently on the arrow-wound, he could feel the fever already building.

"Well," he said to the otter, "all I know to do is to treat you as I did my little brother, the time he fell on the ploughshare. No biting, now." With his dagger, he trimmed the oily brown fur around the injury; with a rag dipped in hot

nihonshu,

which others call

sake,

he cleaned the area over and over; and with herbal infusions whose use he had learned from his mother's mother, he did his best to draw the infection. Through it all the otter never stirred or protested, but watched him steadily as he labored to undo the damage he had caused. He sang softly now and then, old nonsensical children's songs, hardly knowing he was doing it, and now and then the otter cocked an ear, seeming to listen.

When he was done he offered the water again, and this time the otter drank from the dish, cautiously, never taking its eyes from him, but deeply even so. Junko then lifted it in the old cloak and set all upon his own

tatami

mat, saying, "I cannot bind your wound properly, but healing in open air is best, anyway. And now you should sleep." He covered the otter with his coat, then lay down near it on the

tatami

and quickly fell asleep himself. The otter was awake longer than he, its wide eyes darker than the darkness.

In the morning the gash in the otter's flank smelled far less of fever, and the little animal was clearly hungry. Knowing that otters eat mainly fish, along with such things as frogs and turtles, Junko dressed hurriedly and went to a river that was near the castle (the better for the

daimyo

to keep an eye on the boats that went up and down between the distant cities), and there he caught and cleaned several small fish and brought them back to his quarters. The otter devoured them all, groomed its fur with great care -- spending half an hour on its exposed wound alone -- and then fell back to sleep for the rest of the day, much of which Junko spent studying it, sitting crosslegged beside his

tatami

. He was completely captivated to learn that the otter snored -- very daintily and delicately, through its diamond-shaped nose -- and that it smelled only slightly of fish, even after its meal, and much more of spring-warmed earth, as deep in winter as they were. He touched its front claws and realized that they were almost as hard as armor.