Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy (5 page)

Read Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy Online

Authors: David O. Stewart

Tags: #Government, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Executive Branch, #General, #United States, #Political Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Southern whites blanched at “the degradation of being guarded by these runaway slaves of theirs. To be conquered by the Yankees was humiliating, but to have their own negroes armed and set over them they felt to be cruel and wanton insult.” Forty years later, a Southerner remembered with horror the experience of having “an alien race, an ignorant race, half-human, half-savage, above them.” Freedom for the slaves, she concluded, “was inversion, revolution.”

The man in the White House shared those feelings. In September 1865, President Johnson sent a telegram to the army commander in East Tennessee, his home region. The president insisted that Negro troops be withdrawn from the area, which the Negro soldiers had “converted into a sink of pollution.” His own house in Greeneville, Johnson protested, was being used as a “rendezvous for male and female negroes who have been congregated there, in fact making it a common negro brothel.” The commander replied that he had no alternative to Negro troops. He added, without elaboration, that the president’s son-in-law had lodged a white family in the president’s home.

The duties of occupation were far different from those of combat. As one general wrote, “you have not only to be a soldier, but must play the politician,” a part which many soldiers found “not only difficult but disagreeable.” General William Tecumseh Sherman complained that the Army was “left in the breach to catch all the kicks and cuffs of a war of races, without the privilege of advising or being consulted beforehand.” A third general, detailed to the Freedmen’s Bureau, stressed how difficult it was to keep peace with white Southerners who say “they are overpowered, not conquered,” and who “regard their treason as a virtue, and loyalty as dishonorable.”

The assignment was a minefield, the conflicts unceasing. Black soldiers felt resentment toward the region that had practiced slavery so long, while many Southerners nursed hatreds from the war. As Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase wrote during a Southern tour in May 1865, “As yet the rebels are disarmed only, not reconciled, hardly acquiescent.” Southern whites brought lawsuits against army officers for false arrest, damage to property, murder, and assault. Local officials arrested federal soldiers for small infractions of local ordinances. Far more alarming were the outright murders of soldiers. In South Carolina in 1865, three soldiers from Maine were “shot from behind,…killed because they were Yankees.” Five more were killed in the western part of the state. Two Freedmen’s Bureau agents were murdered in Mississippi, another in Texas. Texas grand juries refused to indict those accused of shooting down Union soldiers. State militias and “home guards” posed an armed threat to federal troops and complicated many situations.

The Army’s task would grow more difficult after political warfare broke out between Congress and the president over how reconstruction should proceed. From month to month, the Army’s mandate, and precise instructions, would change dramatically as Congress enacted a new statute, or Johnson’s attorney general issued a new interpretation of the last one, or the president replaced a regional military commander to soften the occupation, which he did repeatedly.

In the coming conflict between Johnson and the Congress, control of the Army would become the great prize. Countervailing pressures drew its senior officers—particularly Grant and his second, William T. Sherman—into highly political situations. During a critical point in the contest for control of the Army, Sherman wrote to Grant, “We ought not to be involved in politics, but for the sake of the army we are justified in trying at least to cut this Gordian knot, which they do not appear to have any practicable plan to do.”

There would never be enough troops and Bureau agents to pacify the angry South. At its peak, the Freedmen’s Bureau had only 900 agents, some of whom sympathized with Southern whites, not with the freedmen. To patrol the Rio Grande border with Mexico and to occupy all of Texas, the Army had only 5,000 men.

The situation between 1865 and 1867 satisfied no one. The president had returned the state governments to the control of former Confederates, which infuriated Stevens and many Northerners. Southern black codes stoked their rage higher, as did the president’s amnesty program, while the freed slaves remained at the mercy of their former masters, enjoying only fitful protection from the Army and the Freedmen’s Bureau. In November of 1865, as the new Southern senators and congressmen began to arrive in Washington City, the fear spread among Republicans that Johnson was allowing the South to control the national government it had spurned only four years before. Effective reconstruction required a political strategy, not a military one, and that would require agreement between Congress and the president. Instead, the two branches of the government were spoiling for a showdown.

DECEMBER 1865

Contemning all applause, defying all censure, incapable of meekness,…this man [Thaddeus Stevens] has no ambition…. [N]o position in the gift of his State or of the United States could give him the power which he now holds in the House of Representatives…. [He is the] greatest…of the politicians.

G

ALAXY

M

AGAZINE

, J

ULY

1866

I

N LATE NOVEMBER,

a few days before Congress was to begin its new session, Thaddeus Stevens invited a group of Republican chieftains to his modest home near the Capitol. From his post as chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, Stevens aimed to mobilize the new Congress. His message was urgent: Congress must save the nation from the policies of Andrew Johnson. Stevens had a plan to do that.

The Republicans at the meeting enjoyed large majorities in Congress, but were a fractious lot. Across the spectrum, from the Radicals through the moderates to the conservatives, strong personalities kindled sharp clashes. Indeed, uniting Republicans was often beyond the powers of even Old Thad. For the next two years, Republican unity would be produced largely by the infuriating actions of the man in the White House.

After Stevens, the best-known Radical was Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, a strapping dandy at six feet four who started in life as an academic lawyer lecturing at Harvard. Never adept in extemporaneous exchanges, Sumner disdained Senate debate. He preferred to rise up to his full height and deliver powerful written addresses that sparkled with classical allusions. When the Massachusetts senator prepared a major speech, his landlord could hear his “magnificent voice rehearsing…[before a mirror] studying the effect of his gestures by the light of lamps placed at each side of the mirror.” Sumner costumed himself for his orations, favoring bright colors, particularly “a brown coat and light waistcoat, lavender-colored or checked trousers, and shoes with English gaiters.”

After delivering a harsh anti-South speech in 1856, Sumner was at his Senate desk when a South Carolina congressman began beating him with a cane. With his legs trapped under the desk and no one coming to his aid, Sumner absorbed the blows until he fell unconscious. He did not recover for more than two years. Though Sumner’s credentials as an abolitionist were impeccable, a contemporary insisted that his “love for the negroes [is] in the abstract,” and that the New Englander was “unwilling to fellowship with them.”

Much about Sumner was in the abstract. For all his oratorical prowess, he was not an effective legislator. A Radical colleague observed that in twenty-three years as a senator, Sumner sponsored a single bill that became law; it barred the naturalization of Mongolians as U.S. citizens.

The obstacle was the vast Sumner ego. When an old friend expressed unhappiness that the senator had not called on her, Sumner explained that because of his involvement in great public questions, he had “quite lost interest in individuals.” Even the taciturn Ulysses Grant could score off the New Englander’s gigantic self-regard. Told that Sumner did not believe in the Bible, Grant replied, “No, he didn’t write it.”

Where Sumner was a product of Boston drawing rooms, Bluff Ben Wade of Ohio was a man of the frontier. Thin and wiry, dressed unfailingly in a black suit with a black stovepipe hat, his voice was shrill, his words plain and often profane. Days after Sumner’s brutal beating in 1856, Wade proclaimed on the Senate floor that if anyone else wished to throttle free discussion, “let us come armed for the combat; and although you are four to one, I am here to meet you.” As he waited for Southerners to challenge him, Wade boasted to friends that his choice of dueling weapons would be squirrel rifles at thirty paces. He also conspicuously placed two pistols on his Senate desk when he took his seat. No Southerner challenged him or tried to beat him to a bloody pulp. One Northerner exulted in the Ohioan’s “manliness, courage, vehemence, and a certain bulldog obduracy truly masterful.”

The best tale of Wade’s pugnacity came from a congressman who rode with him to view the First Battle of Bull Run in the summer of 1861. When Union troops stampeded from the battlefield in a frenzy, desperate to get to safety, some encountered an unexpected barrier. Brandishing his squirrel rifle, the sixty-year-old Wade had upended two carriages to block the road. He manned the barricade with two other legislators and the Senate’s sergeant-at-arms. With “hat well back, his gun in position, his party in line,” the senator called out, “‘Boys, we’ll stop this damned runaway.’” Facing “the onflowing torrent,” the legislators held back the tide for “a fourth of an hour,” then yielded the position to a senior army officer.

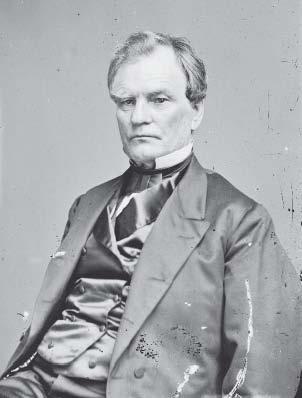

Senator Ben Wade of Ohio, Radical Republican and President Pro Tem of the Senate in 1867–68.

Because Wade would be elected president pro tem of the Senate in 1867, and thus become next in line for the presidency under the laws of the day, his penchant for controversy would be a major influence on whether Congress would expel Andrew Johnson from office. Wade’s strong views and frontier idiom, with liberal Anglo-Saxonisms, alienated less radical Republicans. According to future President James A. Garfield, conservatives found Wade to be “a man of violent passions, extreme opinions, and narrow views.”

A westerner by the geography of the 1860s, Wade believed in cheap money and high tariffs, positions that alarmed the sound-money men of the Republican Party. An advocate for human rights, he supported the eight-hour workday and the ability of women to own property. Wade explained his support for female suffrage in homely terms: “If I had not thought my wife to be as intelligent as I, or as capable of voting understandingly, I would not have married her.” In 1864, Wade’s frustration with President Lincoln’s lenient ways with Southerners led the Ohioan to join a fiery manifesto that denounced Lincoln (his fellow Republican) in the midst of the presidential campaign. In short, Wade terrified Republican conservatives and moderates (the terms were sometimes used interchangeably).

The leading moderate Republican in the Senate, William Pitt Fessenden of Maine, could not abide either Wade or Sumner. Some regarded the lean, reserved Fessenden to be the Senate’s finest legislator, though one observer thought he might easily be overlooked in a crowd. The man from Maine could employ an acid sarcasm. Confronting the claim that Nevada needed only “a little more water, and a little better society” to become a state, Fessenden snapped, “That’s all that hell wants.”

Fessenden’s talents won for him important assignments in the Senate, and he served for key months in 1864 as Lincoln’s treasury secretary. Yet Fessenden, “a martyr to dyspepsia,” could be ill tempered. He once referred to Charles Sumner as the “meanest and most cowardly dog in the parish.” Sumner fired back in a newspaper interview, claiming that Fessenden entered Senate debate “as the Missouri enters the Mississippi and discolors it with temper, filled and surcharged with sediment.”

With his “cold, dry, severe manner,” Fessenden never got along with Ben Wade. In 1867, he would oppose Wade in the contest to be president pro tem of the Senate. Wade’s handy victory would cement Fessenden’s resentment toward Wade and the Radicals who voted for Wade. The resentment was reciprocal. Radicals knew that the senator from Maine tried to maintain friendly relations with President Johnson, even as he despaired of the president’s policies. After almost a year of pitched battle between Congress and Johnson, Fessenden could still write to a friend, “Say what they will, Andy is a good hearted fellow.” Fessenden’s estrangement from the Radicals—and his contempt for Ben Wade—would figure significantly in the impeachment struggle.

John Bingham of Ohio led the moderate and conservative Republicans in the House of Representatives. With long fair hair and sharp blue eyes, the slender Bingham had a nervous, intense quality and was memorably described as “the best-natured and crossest-looking man in the House.”

Sporting credentials as a superior lawyer, Bingham had been the lead “House manager” (prosecutor) in the 1862 impeachment trial of a Tennessee judge who accepted an office in the Confederate government. Bingham also prosecuted the Booth conspirators, convicting all of them before a military commission. One of Johnson’s Cabinet members considered Bingham “a shrewd, sinuous, tricky lawyer.” His lasting legacy is the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment, which requires that the states provide “due process of law” and “equal protection of the laws” because Bingham insisted that they must. Yet Bingham quarreled frequently with the Radicals, even with the ferocious Stevens. One observer thought the Ohioan achieved eloquence only in the face of “provocation, contradiction, and interruption,” as the “more frequently he was interfered with and baited in the discussion, the more vigorous was his logic.”

For this cantankerous group of Republicans to pull together, they would have to face a common foe of distressing proportions. In only seven months, Andrew Johnson had transformed himself into just such a figure. The Republicans also would need the leadership of someone with the political skills to pry Johnson’s hands from the rudder of the government and then steer the nation in an entirely different direction. Only Thaddeus Stevens could perform that role.

Historical depictions of Stevens usually emphasize his iron will, portraying him as a single-minded zealot never deterred from his path. The Pennsylvanian surely was fierce in pursuit of the goals he cared deeply about, but this traditional portrait neglects the vision, tactical sense, and charm that a legislative leader must have in order to command the loyalty of self-interested politicians. Even though he was a harsh adversary on the floor of the House, Stevens maintained cordial relations with many foes. As one put it, “politically we differed,…personally we were the best of friends.” Another remembered him as “above the vulgar habit of allowing differences of political opinion to disturb social relations.” One colleague fondly recalled that Stevens “made more fun for me to laugh at than any other man in Congress.” Despite the passion of his convictions, Stevens was practiced in the art of compromise. Even Andrew Johnson agreed that Stevens would accept the best deal he could get under the circumstances. “I always liked him for it,” the president said in late 1866. “A practical man.”

To defeat the policies of the president and substitute his own, Stevens would need all of the weapons in his possession.

Stevens’s guests traveled to his house through a largely unimpressive city. From the very first, when John Adams moved into the White House in 1800, Washington City tended to disappoint Americans. The capital seemed small and muddy, not a proper setting for titanic national dramas. When the Civil War came in 1861, only Pennsylvania Avenue was paved, yet even there the mud could stop an entire mule team. Other streets alternated between mud and dust, depending on the weather. Plain homes were widely spaced. Without sewers, a longtime resident wrote, “The Capital of the Republic had more mal-odors than the poet Coleridge ascribed to ancient Cologne.”

The war transformed Washington from a sleepy Southern town of 60,000 to a military camp of 250,000, crowned by the mighty Capitol dome, which was completed in time for the inauguration in March 1865. For four years, the city was overrun by armies of soldiers, by the men and women who supported them and collected wartime taxes, and by former slaves in flight from their owners.

When the armies left, the city shrank to 100,000 souls. Government buildings still dominated, but more ambitious private residences began to rise. The federal bureaucracy retracted a bit, but not to its prewar dimensions. To accommodate those clerks and other workers—and the congressmen and lobbyists who descended on a seasonal basis—the city spawned a forest of boardinghouses. Due to the limited hygienic resources at most boardinghouses, the Capitol basement included a row of hot-water baths so congressmen could clean up before striding out onto the national stage.

In those days before congressional office buildings, public business often was conducted in hotel lobbies, barrooms, and private homes. A restaurant notice poked fun at the uprooted congressmen who frequented it: “Members of Congress will go to the table first, and then the gentlemen. Rowdies and blackguards must not mix with the Congressmen, as it is hard to tell one from the other.”

For those with the resources, Washington City could offer better than the basic boardinghouse. Willard’s Hotel, the National Hotel, and the Metropolitan lined Pennsylvania Avenue between the White House and the Capitol. Finer homes clustered toward the White House end of the nation’s main street. Near the Capitol, most dwellings were simple, the streets unpaved and mostly unlighted.

Having prospered as a lawyer and iron manufacturer, Stevens could afford better than a boardinghouse. In an area just west of the Capitol, which is now part of the National Mall, he set up housekeeping with Mrs. Smith at 213 South B St., a two-story structure. The neighborhood was quiet, its streets mostly empty. A newspaper correspondent described the dwelling as “a small dilapidated brick house.” The location was convenient to several faro houses where the congressman liked to gamble in the evenings, particularly Pemberton’s on Pennsylvania Avenue. Some of these establishments aped the luxuries of a London men’s club, but Stevens concentrated on gambling, not amenities. He also bet heavily on elections, risking $100,000 on one governor’s race in Pennsylvania. There is no record that he ever lost more than he could afford.