In Amazonia (34 page)

Authors: Hugh Raffles

Açaà is both seasonal and perishable. In Igarapé Guariba and along the Amapá floodplain, the harvest lasts from January to June. At other times, the Macapá retailers are supplied from Belém. Despite this, there is still a between-harvest period when demand is high and supply low. In these few weeks at either end of the season, dockside prices in Macapá can reach extravagant heights.

33

This is the moment when rural suppliers like the Macedos stand to make a significant profit. But they

have to weigh this temptation against the potential losses in the middle of the season when atravessadores can beat them down as far as they like, and prices drop so low that boat owners throw sacks of fruit overboard rather than waste fuel carrying it back to the rivers. The existing solution to this dilemma is for the rural supplier to contract with the fornecedoresâan arrangement, like that between contractor and retailer, that draws on and may create enduring social networks and cultural ties.

To guarantee delivery to his urban retailers, Jacaré sets quotas with the Macedo brothers and his other rural suppliers through a rolling-over, two-month, fixed-price contract. José Macedo and the other boat owners accept that the price at the beginning of the harvest, when fruit is in short supply and dockside prices are high, will be lower than if they sell independently to the atravessadores. But they also know that later on, when the market is glutted, they will have a guaranteed buyer at a subsidized price.

Such contracts discipline the rural suppliers at the same time as they squeeze the atravessadores who normally operate without contracts, taking from the boats on consignment, and selling on the quayside to independent retailers. At either end of the harvest, when supplies are low and prices high, and in an echo of Old Man Viega's attempt to establish monopsony on the river, Jacaré works to intimidate a rural supplier like José from dealing with the atravessadores. José is always under pressure from his own fregueses back in Igarapé Guariba to achieve the highest dockside prices available. But he knows that if he shortchanges Jacaré at this time of year by selling outside the contract and only providing a portion of the promised sacks, the supplier will quickly find outâand that he's liable to respond by refusing to renew the contract for the following season. In the mid-season glut, however, when the boats are laden and the quayside atravessadores are aggressively beating down the price until the rural collectors are close to despair, Jacaré, in a move characteristic of the Amazonian patrão will at times buy the worthless excess fruit from his contractees and absorb the loss.

The post-harvest quietus marks a period of considerable uncertainty for José and the other boat owners of Igarapé Guariba. This is when they search for the contracts that will protect them from the free market at the dockside for another season. A deal with Jacaré on its own will neither keep them in business nor satisfy their fregueses, and they

scramble to compete for other arrangements. Not counting the Colonel's vessel, there are three motorized boats in Guariba: two, the

Star of Guariba

and the

United We Conquer

belong to José and his brothers. The other is Sônia's

Immaculate Conception

.

S

OCIAL

W

ORK

José Macedo and his brothers fret unceasingly about their ability to lead the community. Their work is development and modernization, the work of place-making. And here, right now, açaà is kingâeven though it brings to the fore some painful contradictions.

During the açaà season, each boat makes at least two trips a week to Macapá. They leave with the tide to save fuel, but they start off by making a tour of the river to collect fruit. The Macedo brothers pick up sacks according to a controversial quota they allocate at the start of the season. The quota fixed in Igarapé Guariba is directly derived from that set by Jacaré. Indeed, the brothers calculate it from their contractsâthe winning of which is the mark of their commitment to community progress and the justification of their leadership. It is, they make clear to me, a terrible responsibility.

José and his brothers allocate quotas by family size: the larger the family the more sacks they allow per voyage. But it is a system with ample room for arbitrariness and patronage, and the quota is a constant source of friction. A persistent theme of conversation in Guariba is how much better things could be if the Macedo brothers would “liberate the quota.” Instead of the two, or sometimes three, sacks allowed, collectors say they could harvest eight or even ten. This may be true, but it is also just talk.

34

Everybody here understands the political economy of açaà and the rationale of the contract. Everyone knows how the market crashes in the middle of the season and that the quota is only part of the problem.

For one thing, there are strategies for circumventing it. Some people who live near the mouth of the river strike deals with traders who cast anchor out in the rio-mar toward the end of the season. They load their canoes with sacks and paddle out into the Amazon to complete the sale. Others use kin networks to pass fruit to boat-owning relatives on neighboring rivers. Such tactics are keenly reminiscent of the old-time traders who used to travel the river at night to escape Old Man Viega's policing.

For the Macedo brothersâeven as they were for Viegaâsuch activities are destructive of community cohesion. After all, it is through the distributed profits of the açaà trade that modernity is arriving in Igarapé Guariba. But many of their fregûes-comrades dismiss such rhetoric. The real issue for them is not how much the Macedos can sell, but how much and at what price they buy. Implicit is a critique of the contradiction between the egalitarian discourse of community and the conspicuous improvements in the material life of the Macedos themselves since the boom began and they started accumulating gas-fired fridges, oil-powered chainsaws, and the big, soft couches from which to watch their new battery-operated TV sets.

It was a long time before I found out that no matter what Jacaré or the atravessadores are paying in Macapá, the Macedo brothers buy açaà in Igarapé Guariba for 40 percent less. When I first heard this, wrapped up as I was in the heroics of the exodus from the other bank and the expulsion of the old regime, I was stunned. But I confirmed it straightaway with José. If Jacaré is giving them R $20 a sack, they pay the fregûes R $12. If Jacaré is offering R $16, they buy for R $9.

35

But what about this unified community I heard so much about, marching forward together, out from the dark days of Old Man Viega's slavery?

José is a sincere man, someone who fought long and hard in church organizations and rural workers' unions for the rights and dignities of rural Amazonians, not only for the removal of the one Old Man from this river. He doesn't need me to point out the contradictions. Any defensiveness he might feel talking about these prices soon dissipates in the enumeration of the responsibilities and expenses of running a boat and in the conviction that boats are the indispensable vehicles of community progress, that a riverine community

must

support the boats that hold it in the world and the boat owners who take this charge upon themselves. The stresses of cultivating and maintaining the social networks that enable the contracts and create other future possibilities are near-overwhelming. There's no time to stand still. And he continues by pointing to the daily solidarities of his regime: we rarely refuse to carry people upstream on expeditions to hunt, fish, farm, and harvest açaÃ. Nor do we charge freight when we take their produce into Macapá and bring their shopping home. And neitherâlike Gordão in Carapanatuba and all those guys in Bailiqueâare we making people pay R $5 or R $10 for the trip into town, even though sometimes the boat is so

overloaded you think it will never make it (and who knows how much gasoline is being wasted).

But somehow this logic doesn't mend the fractures through which Sônia sails. She has another system and offers another vision of life on the river. She works to demand, avoiding the symbolic contamination of the hated quota. In her discursive ordering of the trade, she is transporting fruit without constraint at the behest of the collectors. On the day before her voyage, she tours her clients' houses and drops off sacks, stopping just long enough to negotiate quantity. How much can they give her? She'll take all they've got. Then, at the hour of sailing, she might make more visits just in case someone has a little extra to sell. She sets her price by marginally but significantly trumping the Macedos. If they give R $12, she pays R $14. If they pay R $9, she gives R $11. Like them, she too discounts açaà against orders for household goods she fills on credit with her patrões in the stores that line the dock in Macapá. But whereas they scrupulously charge their clients the same retail price they pay in town, back in Igarapé Guariba, Sônia sells this merchandise at large mark-ups directly across the counter in her store in the tile-roofed house at the river's mouth, reclaiming the profit she has lost in attracting custom, reviving the ghost of her husband's grandfather.

What really infuriates the Macedos and invigorates politics in Igarapé Guariba as a soap-opera feud between two powerful families is the way Sônia and Miguelinho trade açaà for shots of cane liquor at their bar the whole day long, until the cash-poor caboclo is too drunk to buy any more and has to be carried down to his canoe and floated off back to his family. For José Macedo, such corrupting practices and public humiliation exemplify the continuity between past escravidão and contemporary disunity, a holdover personified by these last of the parasitic Viegas.

There are other disappointments and betrayals. For José, it is ingratitude and lack of vision that drive his neighbors to sell açaà marked for him to Sônia. Sometimes he arrives as scheduled at the house of an Association member to be told that the man did not harvest açaà that day. Yet later, in dismay, he learns that Sônia is traveling the same night with a full shipment that includes açaà from that very house. Arriving in Macapá half-empty, José shares the sacks out evenly among his disgruntled buyers, excusing the shortfall, promising it is not going to happen again, feeling the next year's contracts sliding through his fingers.

On the days before they head into Macapá, the Macedo brothers organize trips to an upstream area of forest that was divided into large family-owned lots following Viega's departure. Small groups of invited men, the occasional woman, and a smattering of teenage boys arrive at Seu Benedito's house with the first tide and tie their canoes to the back of the boat. They sit on the porch in the dark, smoking and talking softly, pouring coffee from Seu Benedito's thermos, slapping at mosquitoes and long-legged

muriçocas

.

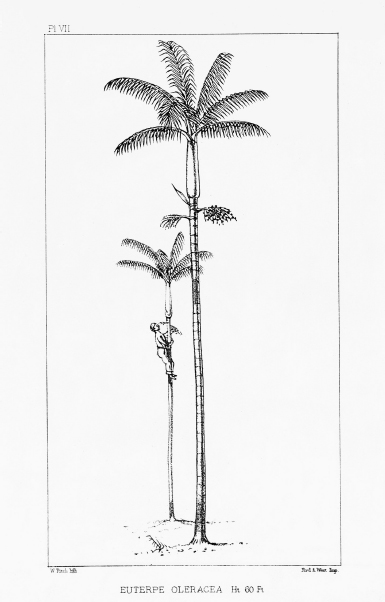

It takes an hour to get upstream. When the boat moors, everyone separates into twos or threes and paddles out to an area of their own land where they expect to find ripe açaÃ. Collecting takes most of the day. Someone spots a tree laden with dark fruit. They climb the smooth trunk, feet gripping a twisted sack or palm-frond for purchase, cut the heavy bunch with their machete, and bring it carefully down, trying not to lose too much on the way. Back on the ground, one or two people strip the fruit from its woody stalks and fill sacks provided by the boat owners. It is rough, dangerous work, hard on hands and feet, made worse by the relentless insects.

The emphasis is on speed and volume. On a good dayâif it does not rain, if no one gets injured, if there are big bunches and short treesâtwo people might collect four sacks, each holding the fruit from seven or eight bunches. But to do that, collectors have to cut corners, boosting quantity by throwing in unripe, green fruit, tipping in the dust from the flattened sack on which the berries were stripped, ignoring stalk and leaves that find their way into the sack, not worrying if the seeds are wet.

Back on the boat, the sacks are in the hold. While everyone else sits on the roof in the late afternoon sunshine, talking and finishing their work, José and one of his brothers spend the return trip below, emptying and refilling each sack, carefully checking the contents and sifting out a portion of the debris and impurities. Arriving that night at the crowded dock in Macapá, José delivers his cargo to Jacaré's agent, who caps the transaction by emptying the sacks and transferring the fruit to new ones, again checking the contents for debris and impurities, continuing the ongoing, recursive performance of public surveillance.

Sônia will leave Miguelinho for good one day. At least that is what Miguelinho's sister Eliana tells me at four in the morning as we sit bundled up together on the waterline at the back of a battered launch,

watching the foamy wake ripple out into the forest darkness. We are heading to Macapá loaded down with açaÃ, and Eliana is going back to start her day as a maid in the city.

Sônia is “uma grande mulher,” a great women, says Eliana, and one day she'll take the

Immaculate Conception

and the kids and start up on her own as a

regatão

, a trader sailing between the islands off Macapá. She might as well. She couldn't work any harder: “She's left many times even though she's scared of him,” Eliana whispers hoarsely above the wake. “But, you know, the man wants to die. That's why he drinks like that. He knows it's killing him.” When I'm talking to Sônia, though, it is so much more confused: “Even beasts feel love,” she says, with an assertive mix of pride and despair.