In Arabian Nights

Authors: Tahir Shah

- Title

- By the Same Author

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Epigraphs

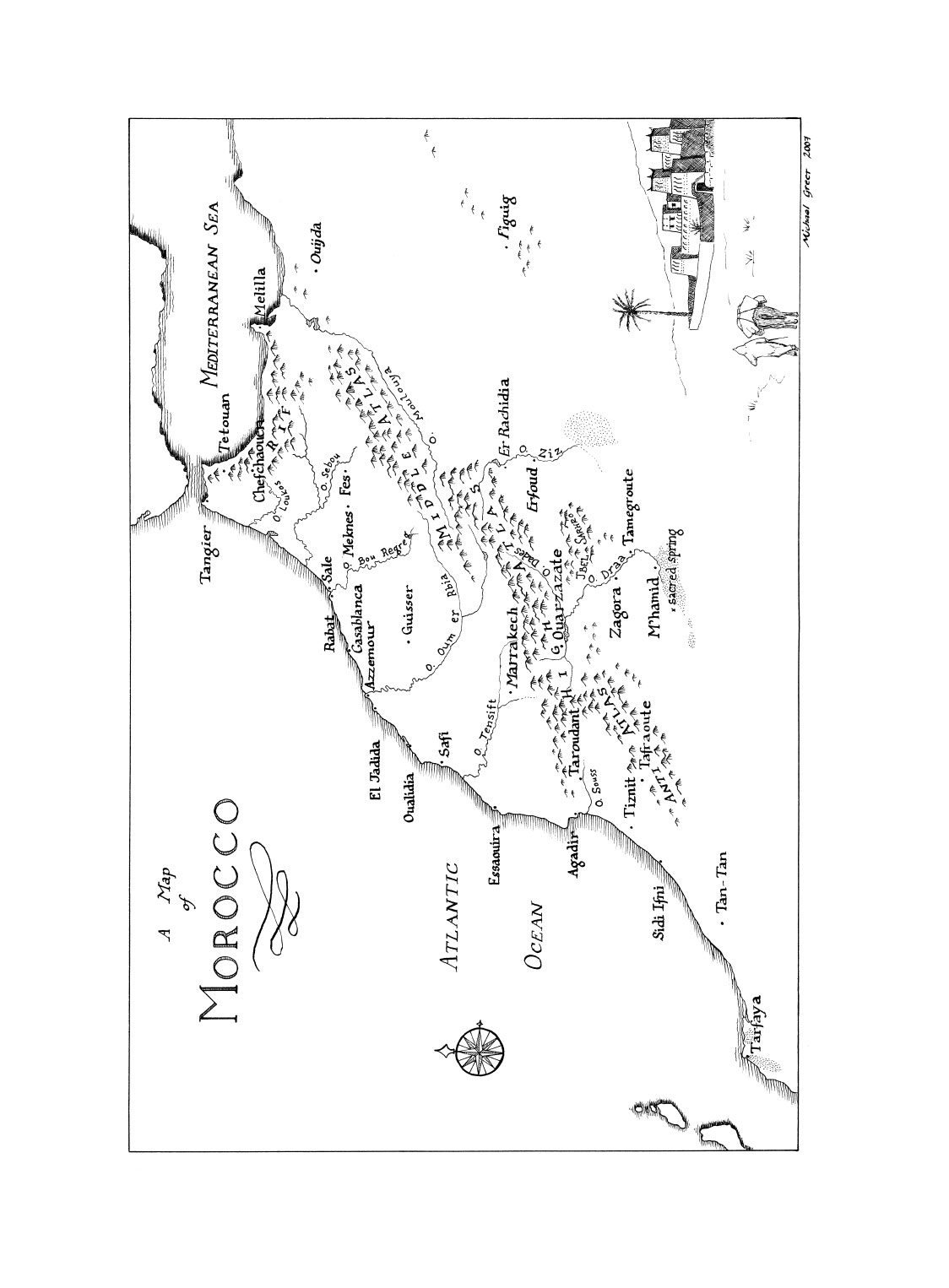

- Map of Morocco

- Chapter ONE

- Chapter TWO

- Chapter THREE

- Chapter FOUR

- Chapter FIVE

- Chapter SIX

- Chapter SEVEN

- Chapter EIGHT

- Chapter NINE

- Chapter TEN

- Chapter ELEVEN

- Chapter TWELVE

- Chapter THIRTEEN

- Chapter FOURTEEN

- Chapter FIFTEEN

- Chapter SIXTEEN

- Chapter SEVENTEEN

- Chapter EIGHTEEN

- Chapter NINETEEN

- Chapter TWENTY

- Chapter TWENTY-ONE

- Chapter TWENTY-TWO

- Chapter TWENTY-THREE

- Chapter TWENTY-FOUR

- Chapter TWENTY-FIVE

- GLOSSARY

- RECOMMENDED READING

IN ARABIAN NIGHTS

Also by Tahir Shah

BEYOND THE DEVIL'S TEETH

SORCERER'S APPRENTICE

TRAIL OF FEATHERS

IN SEARCH OF KING SOLOMON'S MINES

HOUSE OF THE TIGER KING

THE CALIPH'S HOUSE

For more information on Tahir Shah and his books,

see his website at

www.tahirshah.com

NIGHTS

In search of Morocco,

through its stories and storytellers

TAHIR SHAH

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781407040523

Version 1.0

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

61–63 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

A Random House Group Company

www.rbooks.co.uk

First published in Great Britain

in 2008 by Doubleday

an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © Tahir Shah 2008

Illustrations by Laetitia Bermejo

Map by Michael Greer

Tahir Shah has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781407040523

Version 1.0

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

Addresses for Random House Group Ltd companies outside the UK

can be found at:

www.randomhouse.co.uk

The Random House Group Ltd Reg. No. 954009

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This book is for my aunt Amina Shah,

Queen of the Storytellers.

Here we are, all of us: in a dream-caravan.

A caravan, but a dream – a dream, but a caravan.

And we know which are the dreams.

Therein lies the hope.

Sheikh Bahaudin

Nasrudin was sent by the king to find the most foolish man in

the land and bring him to the palace as court jester. The mulla

travelled to each town and village in turn, but could not find a

man stupid enough for the job. Finally, he returned alone.

'Have you located the greatest idiot in our kingdom?' asked

the monarch.

'Yes,' replied Nasrudin, 'but he is too busy looking for fools

to take the job.'

The World of Nasrudin

by Idries Shah

Be in the world, but not of the world.

Arab proverb

THE TORTURE ROOM WAS READY FOR USE. THERE WERE

harnesses for hanging the prisoners upside-down, rows of sharp-edged

batons, and smelling salts, used syringes filled with dark

liquids and worn leather straps, tourniquets, clamps, pliers, and

equipment for smashing the feet. On the floor there was a central

drain, and on the walls and every surface, dried blood – plenty of

it. I was manacled, hands pushed high up my back, stripped almost

naked, with a military-issue blindfold tight over my face. I had

been in the torture chamber every night for a week, interrogated

hour after hour on why I had come to Pakistan.

All I could do was tell the truth: that I was travelling through

en route from India to Afghanistan, where I was planning to

make a documentary about the lost treasure of the Mughals. My

film crew and I had been arrested on a residential street and

taken to the secret torture installation known by the jailers as

'The Farm'.

I tried to explain to the military interrogator that we were

innocent of any crime. But for the military police of Pakistan's

North West Frontier Province, a British citizen with a Muslim

name, coming overland from an enemy state – India – set off all

the alarms.

Through nights of blindfolded interrogation, with the

screams of other prisoners forming an ever-present backdrop to

life in limbo, I answered the same questions again and again:

What was the real purpose of your journey? What do you know

of Al-Qaeda bases across the border in Afghanistan? And, even:

Why are you married to an Indian? It was only after the first

week that the blindfolds were removed and, as my eyes adjusted

to the blaring interrogation lamps, I caught my first burnt-out

glimpse of the torture room.

The interrogations took place only at night, although day and

night were much the same at The Farm. The strip-light high on

the ceiling of my cell was never turned off. I would crouch there,

waiting for the sound of keys and for the thud of feet pacing over

stone. That meant they were coming for me again. I would brace

myself, say a prayer and try to clear my mind. A clear mind is a

calm one.

The keys would jingle once more and the bars to my cell

would swing open just enough for a hand to reach through and

grab me.

First the blindfold and then the manacles.

Shut out the light, and your other senses compensate. I could

hear the muffled screeches of a prisoner being tortured in the

parallel block and taste on my tongue the dust out in the fields.

Most of the time, I squatted in my cell, learning to be alone.

Get locked up in solitary in a foreign land, with the threat of

immediate execution hanging over you, a blade dangling from a

thread, and you try to pass the time by forgetting where you

are.

First I read the graffiti on the walls. Then I read it again, and

again, until I was half-mad. Pens and paper were forbidden, but

previous inmates had used their ingenuity. They had scrawled

slogans in their own blood and excrement. I found myself

desperate to make sense of others' madness. Then I knelt on the

cement floor and slowed my breathing, even though I was so

scared words could not describe the fear.

Real terror is a crippling experience. You sweat so much that

your skin goes all wrinkly like when you've been in the bath all

afternoon. And then the scent of your sweat changes. It smells

like cat pee, no doubt from the adrenalin. However hard you

wash, it won't come off. It smothers you, as your muscles become

frozen with acid and your mind paralysed by despair.

The only hope of staying sane was to think of my life, the life

that had become separated from me, and to imagine that I was

stepping into it again . . . into the dream that, until so recently,

had been my reality.

The white walls of my cell were a kind of silver screen on

which I projected the Paradise I longed to return to. The love for

that home and all within washed out the white walls, the blood-graffiti

and the stink of fear. And the more I feared, the more I

forced myself to think of my adopted Moroccan home, Dar

Khalifa, the Caliph's House.

There were courtyards brimming with fountains and birdsong,

and gardens in which Timur and Ariane, my little son and

daughter, played with their tortoises and their kites. There was

bright summer sunlight, and fruit trees, and the voice of my

wife, Rachana, calling the children in to lunch. And there were

lemon-coloured butterflies, scarlet red hibiscus flowers, blazing

bougainvillea and the hum of bumblebees dancing through the

honeysuckle.

Hour after hour I would watch my memories screened across

the blank walls. I would be blinded by the colours, and glimpse

in sharp detail the lives we had created for ourselves on the edge

of Casablanca. With my future now in the balance, all I could do

was pray. Pray that I might be reunited with that life, a melodious

routine of innocence, interleaved with gentle calamity.

As the days and nights in solitary passed, I moved through the

labyrinth of my memories. I set myself the task of finding every

memory, every fragment of recollection.

They began with my childhood, and with the first moment I

ever set foot on Moroccan soil.

The ferry had taken us from southern Spain, across the Strait

of Gibraltar. It was the early seventies. Tucked up in the northwest

corner of Africa, Tangier was a

mélange

of life like none

other. There were beatniks and tie-dyed hippies, drug dealers

and draft dodgers, writers, poets, fugitives and philosophers.

They were all united in a swirling stew of humanity. I was only

five years old, but I can remember it crystal clear, a world I could

never hope to understand. It was scented with orange blossom,

illuminated by sunshine so bright that I had to squint.

My father, who was from Afghanistan, had been unable to take

my sisters and me to his homeland. It was too dangerous. So he

brought us on frequent journeys to Morocco instead. I suppose it

was a kind of Oriental logic. The two countries are remarkably

similar, he would say: dramatic landscapes, mountain and desert, a

tribal society steeped in history, rigid values and a code of honour,

all arranged on a canvas of vibrant cultural colour.

The animated memories of those early travels were relived on

the whitewashed walls of solitary, mile by mile. As I watched

them, I found myself thinking about the stories my father told as

the wheels beneath us turned through the dust, and how they

bridged the abyss between fact and fantasy.

The interrogations in the torture room came and went, as did

the jangle of keys, the plates of thin soupy

daal

slipped under the

bars, and the nightmares. Through it all, I watched the walls, my

concentration fixed on the matinees and the late

-

night shows

that slipped across them. With time, I found I could navigate

through weeks and years I had almost forgotten took place, and

could remember details that my eyes had never quite revealed. I

revisited my first day at prep school, my first tumble from a tree-climbing

childhood, and the day I almost burned down my

parents' house.

But most of all, I remembered the tales my father told.

I pictured him rubbing a hand over his dark moustache and down

over his chin, and the words that were the bridge into another world: 'Once

upon a time . . .'

Sometimes the fear would descend over me like a veil. I would

feel myself slipping into a kind of trance, numbed by the frantic

debauched screams of the prisoner being worked over in the

torture room. In the same way that a bird in the jaws of a

predator readies itself for the end, I would push the memories

out, struggle to find silence. It only came when the uncertainty

and the fear reached its height. And with it came a voice. It

would ease me, calm me, weep with me, and speak from inside

me, not from my head, but from my heart.

In a whisper the voice guided me to my bedroom at the

Caliph's House. The windows were open, the curtains swaying,

and the room filled with the swish of the wind in the eucalyptus

trees outside.

There is something magical about that sound, as if it spans an

emptiness between restraint and the furthest reaches of the

mind. I listened hard, concentrating to the hum of distant waves

and to the rustle of crisp eucalyptus leaves, and walked down

through the house and out on to the terrace. Standing there, the

ocean breeze cool on my face, I sensed the tingle of something I

could not understand, and saw a fine geometric carpet laid over

the lawn. I strolled down over the terrace and on to the grass,

and stepped aboard it, the silk knots pressing against my bare

feet. Before I knew it, we were away, floating up into the air.

We moved over the Atlantic without a sound, icy waters

surging, cresting, breaking. Gradually, we gathered speed and

height until I could see the curve of the earth below. We crossed

deserts and mountains, oceans and endless seas. The carpet

folded back its edge, protecting me from the wind.

After hours of flight, I glimpsed the outline of a city ahead. It

was ink-black and sleeping, its minarets soaring up to the

heavens, its domed roofs hinting at treasures within. The carpet

banked to the left and descended until we were hovering over a

grand central square. It was teeming with people and life,

illuminated by ten thousand blazing torches, their flames licking

the night.

A legion of soldiers in gilded armour was standing guard.

Across from them were stallions garlanded in fine brocades,

caparisoned elephants fitted with howdahs, a pen of prowling

tigers and, beside it, a jewel-encrusted carousel. There were oxen

roasting on enormous spits, tureens of mutton stewed in milk,

platters of braised camel meat, and great silver salvers heaped

with rice and with fish.

A sea of people were feasting, entertained by jugglers and

acrobats, serenaded by the sound of a thousand flutes. Near by,

on a dais crafted from solid gold, overlaid with rare carpets from

Samarkand, sat the king. His bulky form was adorned in creamcoloured

silk, his head crowned by a voluminous turban,

complete with a peacock feather pinned to the front.

At the feet of the monarch sat a delicate girl, her skin the

colour of ripe peaches, her eyes emerald green. Her face was

partly hidden by a veil. Somehow I sensed her sadness. A platter

of pilau had been put before her, but she had not touched it. Her

head was low, her eyes reflecting a sorrow beyond all depth.

The magic carpet paused long enough for me to take in the

scene. Then it banked up and to the right, flew back across the

world over mountains and deserts, oceans and seas, and came to

a gentle rest on our own lawn.

In my heart I could hear the hum of Atlantic surf, and the

wind rippling through the eucalyptus trees. And in my head I

could hear the sound of keys jangling, and steel-toed boots

moving down the corridor, pacing over stone.