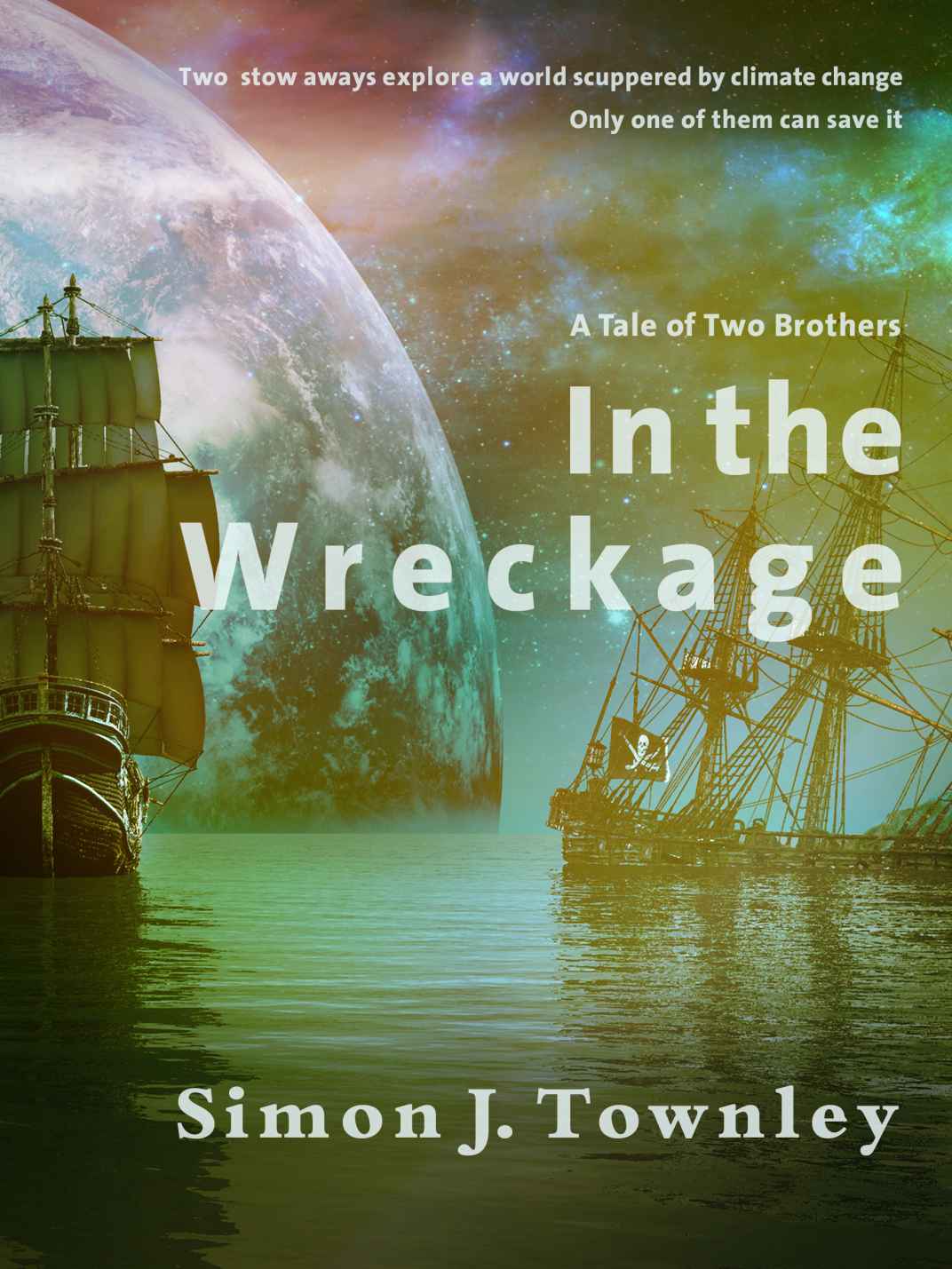

In The Wreckage: A Tale of Two Brothers

Read In The Wreckage: A Tale of Two Brothers Online

Authors: Simon J. Townley

Tags: #fiction, #Climate Change, #adventure, #Science Fiction, #sea, #Dystopian, #Young Adult, #Middle Grade, #novel

Other books by Simon J. Townley

Chapter Eleven - Thieves in the Night

Chapter Thirteen - Storms at Sea

Chapter Twenty - A Cold Shoulder

Chapter Twenty-Two - The Old Timer

Chapter Twenty-Three - Insurrection

Chapter Twenty-Four - Uprising

Chapter Twenty-Five - Ghostlight

Chapter Twenty-Seven - Buried Deep

Author's and publisher's notes

In The Wreckage

(A Tale of Two Brothers)

by

S

IMON

J. T

OWNLEY

Copyright © 2014 Simon Townley. All rights reserved.

Sign up for

new releases newsletter

Published By Beardale Books

http://beardale.com

This text uses British English spelling.

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or to actual events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Other novels by Simon J. Townley

Outlivers

Doguar and the Baboons of War

Lost In Thought

Ball Machine

The Dry Lands (book one of ‘A Tribal Song – Tales of the Koriba’)

In the Rattle of the Shaman’s Bones (book two of ‘A Tribal Song – Tales of the Koriba’)

Soon to be published

Monster Hunters of the Undermire

Wild, Hugo Wilde

Sign up to the

email list here

to receive information on new releases.

C

ASTAWAYS

A sultry wind from the south-west tussled his hair, blowing through his thin cotton shirt. Conall Hawkins lowered his binoculars and wiped sweat from his forehead. Mid-morning and the heat was building, every year hotter than the last: hotter, drier and more desperate.

He crouched on the ground next to his brother. Faro sat with his back to a rock reading a book, battered and torn, about machines and engines, ships, planes and rockets. Impossible stories of flying to the moon.

Conall took the cloth from the case and wiped the lenses of his binoculars. “You seen Rufus?”

“Down a rabbit hole.” Faro pointed to a patch of scraggy grass pitted with burrows.

Conall stood up and tracked with the glasses until he spotted the terrier. The rabbits had gone to ground and the dog sprawled in long grass waiting for his prey to make a false move. Conall scanned across farmland and the Bressay Sound and refocused on the shimmering horizon to the north, a blur of blue and grey.

“Sit down.” Faro didn’t look up from his book. “There’s nothing to see, never is.”

Conall turned in a circle surveying empty ocean flecked with white spray. Faro had it right. There was nothing to see, never had been, not in the five long years since the last ship called at Lerwick and that had sailed by, afraid of slavers or disease. The stream of refugees had withered and dried leaving Shetland becalmed.

He scanned the ocean one last time, then stopped, refocused the glasses, his hands trembling, breath an iron lump in his lungs. On the horizon a speck, nothing more but a speck that grew.

It came this way. He looked away then back again: still there, a sail, dazzling white. He clutched the glasses tighter. At last, a sail, but a ship from the south, the wrong direction. It couldn’t be them.

He lowered his binoculars, handed them to his brother. “Coming straight for us. No fishing boat, she’s huge.”

Faro had the same scruffy black hair as Conall, the piercing blue eyes, the high forehead and penetrating stare. But at twenty, he was five years older, taller and stronger. Faro grunted, as if he thought Conall was imagining things, but he stood up, put the glasses to his eyes and stared to the south.

Conall sat on the ground in the cool of his brother’s shadow, surveying the horizon.

“A white hull,” Faro said at last, “three masts. A monster.” Excitement simmered in his voice. “A steel hull, I swear.”

Conall squinted at the ship, a smudge of white against sea and sky.

“She’s got an engine below decks, I’ll bet,” Faro said. “Oil or coal. I know ships.”

From books, old and yellowed, nothing more, but Conall said nothing. He stood up, reached out to take his binoculars. “Let me see.”

Faro kept the glasses fixed to his eyes. “We should head into town, tell people she’s coming. We saw her first.”

Conall took hold of his binoculars, tugged them from his brother’s hands.

“I wonder what she’s carrying,” Faro said, “she’s heading for Norway, she’ll stop here, for sure, they could be slavers though. Come on, let’s get a closer look.” Faro set off, without waiting for Conall, charging down the hillside, running towards Lerwick, the only place on Shetland where the white ship might make port.

≈≈≈≈

Conall ran through the cobbled streets of the town towards the harbour, following Faro as he shouted to shopkeepers and tradesmen, to fishermen sitting in doorways mending nets and women in the alleyways, hanging up their washing

“It’s a sailing ship,” Faro yelled, intent on being first with the news. “Coming from the south, a sailing ship, you’ll see.” But the townsfolk watched grim-faced, not willing to stir themselves on the word of Faro Hawkins.

The brothers ran to the new harbour and stared across the Bressay Sound, waiting for the sails to appear. The town of Lerwick had retreated uphill as sea levels rose, and the old jetties were drowned. The townsfolk had scavenged stones from half-submerged houses to build a new harbour, large enough for their fishing boats but too small for trading ships. The approaches remained treacherous and shallow, full of half-fallen walls, and crumbling rooftops poking through the waves. The ship must anchor offshore, and the crews come to land by row-boat, if they came at all.

Conall was first to spot the sails poking above the rocky coastline. He pointed to the south, calling on the fishermen to look up from their nets. Still the townsfolk ignored the boys. Only when the ship rounded the headland, her white hull dazzling in the morning sunshine, did the news spread. Now it was wildfire, excitement flowing across the town, voices raised, the sound of feet running from every direction.

“A steel hull, didn’t I say?” Faro stood tall, sticking out his chest, explaining how she was a three masted barque, you could tell by the rig.

The crew were busy taking in the sails. Conall counted more than twenty bustling on deck and in the rigging.

“They’re putting down a boat,” Faro shouted. “The crew are coming ashore.”

Faro grabbed Conall’s arm and dragged him forward, as if the boys should form the welcoming committee, but the town leaders had already gathered by the steps to the new harbour and the boys were pushed back.

Conall could see nothing for the press of bodies in front of him. “Let’s get up the hill, see what’s happening.”

Faro ignored him and barged past a group of women, “I want to hear what they’re saying,” he yelled over his shoulder.

Conall held Rufus tight to his chest and fought his way back through the crush of people, seeking clear air and room to move. The sailors wouldn’t talk, not here on the dockside with this crowd and the barrage of noise. The council leaders would take the captain to the town hall to get news and discuss trade. But what of the crew? Across the Sound two row-boats headed from the ship, carrying more than a dozen men between them.

As a boy Conall had devoured the novels in the library of Lerwick, a communal reading room by the docks. He’d read enough stories of treasure hunts and pirate ships to know what happened next. These were sailors, coming ashore for food and drink, for women and entertainment.

They’d make for an inn. The Old Broch was the closest, the one the fishermen used after days at sea. Conall had worked at the inn, cleaning tables and washing up when they were busy. The landlord might need him now, if these people arrived, unexpected, demanding food and drink in the middle of the day.

He looked for Faro but his brother was lost in the throng by the harbour steps. Conall ran towards the inn, Rufus at his heels. The landlord, a burly man by the name of Ben Harwood, stood in the doorway with his wife and daughter, watching the harbour. Conall rushed up to him.“You’ll be needing help, if you’re short-handed.”

“Maybe,” Ben said, his arms crossed, legs astride, standing in his doorway, king of his own world.

The man’s wife, Mary, whispered something to their daughter, who gave a complaining moan but disappeared inside. “I don’t want her serving. No telling who these people are. Might be slavers for all we know,” Mary said. “Put the boy on the tables, keep the girl out of sight.”

“They’ll take an able-bodied lad soon enough, if they’re slavers,” Ben said.

“But he’s not my son and I’d sooner risk him, if it’s all the same to you,” she said.

Ben looked at Conall and gave a shrug, one man to another, admitting he had little say, and the boy could take the risks if he saw fit. “I’ll pay you in food, guess that’s what you need most. Where’s your brother got to?”

“By the harbour.”

“Trying to run the place as usual? Make the tables ready. I’m for the kitchen. Let’s see what these sailors bring to trade.”

Conall told Rufus to stay outside and busied himself in the main bar, glancing out the windows whenever he could. Across the bay, the ship rocked at anchor. Crewmen cleaned the decks, climbed masts to inspect rigging, and sat in the shade out of the midday heat. The town leaders led their guests towards the hall, but sure enough a group of sailors broke away and headed for The Old Broch.

They wore trousers cut off and frayed below the knee, cotton shirts blustering in the breeze, and an assortment of hats of cotton and wool, black, blue, green and red, that made them look like a gang of pirates in the old books.

Conall shouted to Ben Harwood to tell him the sailors were coming. The landlord rushed from the kitchen and stood stout and determined in his doorway. He waved the sailors forward, standing aside to guide them safely in, but he blocked the entrance to his own townsfolk. “It’s not the pageant,” Ben shouted to the crowd. “No one’s coming in unless they’re eating, drinking and paying on the spot. No credit. No hanging around.”

Conall stood by the bar as the sailors stomped inside, led by a bear of a man with a gnarled and craggy face, carrying a walking stick, though he didn’t seem to need it. A straggle of beard, six inches long, dangled from his chin, braided with red and blue beads. His eyes were dark and deep-set, his forehead wrinkled and scarred. He lifted a broad brimmed hat in mock welcome to Conall, bowed low, and tapped his stick on a table by the window. “Bring us beer,” he said. “Unless you’ve got something stronger?” His canines glinted as he grinned, his eyes shining with mischief.

“Finest whisky in Shetland,” Ben Harwood said as he followed the group of sailors across the bar, ten of them, including the man with the cane, rough-looking and tired, as if they’d spent weeks at sea. “You’ll be wanting to eat I expect, beer’s best with a meal.”

“Bring it all, whisky and beer and the best food,” the man with the stick bellowed, as if competing with a North Sea gale.

“You’ll be having gold or silver, or looking to trade I’d say.” Ben almost whispered the words, as if apologising for having to raise so sensitive a matter.

“Don’t worry, we’ve plenty to pay with,” said the man with the cane. “Good as our word, men of the sea, we never cheat a man who brings good ale.”