Incognito (27 page)

Authors: David Eagleman

What accounts for the shift from blame to biology? Perhaps the largest driving force is the effectiveness of the pharmaceutical treatments. No amount of beating will chase away depression, but a little pill called

fluoxetine often does the trick. Schizophrenic symptoms cannot be overcome by exorcism, but can be controlled by

risperidone. Mania responds not to talking or to ostracism, but to

lithium. These successes, most of them introduced in the past sixty years, have underscored the idea that it does not make sense to call some disorders brain problems while consigning others to the ineffable realm of the psychic. Instead, mental problems have begun to be approached in the same way we might approach a broken leg. The neuroscientist

Robert Sapolsky invites us to consider this conceptual shift with a series of questions:

Is a loved one, sunk in a depression so severe that she cannot function, a case of a disease whose biochemical basis is as “real” as is the biochemistry of, say, diabetes, or is she merely indulging herself? Is a child doing poorly at school because he is unmotivated and slow, or because there is a neurobiologically based learning disability? Is a friend, edging towards a serious problem with substance abuse, displaying a simple lack of discipline, or suffering from problems with the neurochemistry of reward?

20

The more we discover about the circuitry of the brain, the more the answers tip away from accusations of indulgence, lack of motivation, and poor discipline—and move toward the details of the biology. The shift from blame to science reflects our modern understanding that our perceptions and behaviors are controlled by inaccessible subroutines that can be easily perturbed, as seen with the split-brain patients, the frontotemporal dementia victims, and the Parkinsonian gamblers. But there’s a critical point hidden in here. Just because we’ve shifted away from blame does not mean we have a full understanding of the biology.

Although we know that there is a strong relationship between brain and behavior,

neuroimaging remains a crude technology, unable to meaningfully weigh in on assessments of guilt or innocence, especially on an individual basis.

Imaging methods make use of highly processed blood-flow signals, which cover tens of cubic millimeters of brain tissue. In a single cubic millimeter of brain tissue, there are some one hundred million synaptic connections between neurons. So modern neuroimaging is like asking an astronaut in the space shuttle to look out the window and judge how America is doing. He can spot giant forest fires, or a plume of volcanic activity billowing from Mount Rainier, or the consequences of broken New Orleans levies—but from his vantage point he is unable to detect whether a crash of the stock market has led to widespread depression and suicide, whether racial tensions have sparked rioting, or whether the population has been stricken with influenza. The astronaut doesn’t have the resolution to discern those details, and neither does the

modern neuroscientist have the resolution to make detailed statements about the health of the brain. He can say nothing about the minutiae of the microcircuitry, nor the algorithms that run on the vast seas of millisecond-scale electrical and chemical signaling.

For example, a study by psychologists

Angela Scarpa and

Adrian Raine found that there are measurable differences in the brain activity of convicted murderers and control subjects, but these differences are subtle and reveal themselves only in group measurement. Therefore, they have essentially no diagnostic power for an individual. The same goes for neuroimaging studies with psychopaths: measurable differences in brain anatomy apply on a population level but are currently useless for individual diagnosis.

21

And this puts us in a strange situation.

Consider a common scenario that plays out in courtrooms around the world: A man commits a criminal act; his legal team detects no obvious neurological problem; the man is jailed or sentenced to death. But

something

is different about the man’s neurobiology. The underlying cause could be a genetic mutation, a bit of brain damage cause by an undetectably small stroke or tumor, an imbalance in neurotransmitter levels, a hormonal imbalance—or any combination. Any or all of these problems may be undetectable with our current technologies. But they can cause differences in brain function that lead to abnormal behavior.

Again, an approach from the biological view point does not mean that the criminal will be exculpated; it merely underscores the idea that his actions are not divorced from the machinery of his brain, just as we saw with

Charles Whitman and

Kenneth Parks. We don’t blame the sudden pedophile for his tumor, just as we don’t blame the frontotemporal shoplifter for the degeneration of his

frontal cortex.

22

In other words, if there is a measurable brain problem, that buys leniency for the defendant. He’s not really to blame.

But we

do

blame someone if we lack the technology to detect a biological problem. And this gets us to the heart of our argument:

that blameworthiness is the wrong question to ask

.

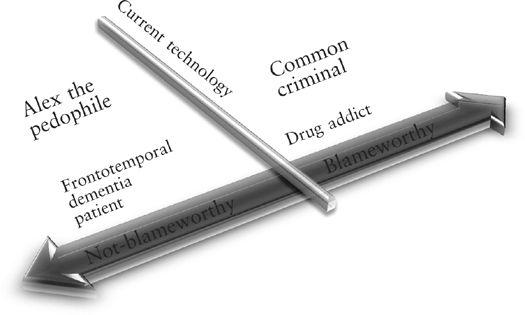

Imagine a spectrum of culpability. On one end, you have people like Alex the pedophile, or a patient with frontotemporal dementia who exposes himself to schoolchildren. In the eyes of the judge and jury, these are people who suffered brain damage at the hands of fate and did not choose their neural situation.

On the blameworthy side of the fault line is the common criminal, whose brain receives little study, and about whom our current technology might be able to say very little anyway. The overwhelming majority of criminals are on this side of the line, because they don’t have any obvious biological problems. They are simply thought of as freely choosing actors.

Somewhere in the middle of the spectrum you might find someone like Chris Benoit, a professional wrestler whose doctor conspired with him to provide massive amounts of testosterone under the guise

of hormone replacement therapy. In late June 2007, in a fit of anger known as

steroid rage, Benoit came home, murdered his son and wife, and then committed suicide by hanging himself with the pulley cord of one of his weight machines. He has the biological mitigator of the hormones controlling his emotional state, but he seems more blameworthy because he chose to ingest them in the first place.

Drug addicts in general are typically viewed near the middle of the spectrum: while there is some understanding that addiction is a biological issue and that drugs rewire the brain, it is also the case that addicts are often interpreted as responsible for taking the first hit.

This spectrum captures the common intuition that juries seem to have about blameworthiness. But there is a deep problem with this. Technology will continue to improve, and as we grow better at measuring problems in the brain, the fault line will drift toward the right. Problems that are now opaque will open up to examination by new techniques, and we may someday find that certain types of bad behavior will have a meaningful biological explanation—as has happened with schizophrenia, epilepsy, depression, and mania. Currently we can detect only large brain tumors, but in one hundred years we will be able to detect patterns at unimaginably small levels of the microcircuitry that correlate with behavioral problems. Neuroscience will be better able to say why people are predisposed to act the way they do. As we become more skilled at specifying how behavior results from the microscopic details of the brain, more defense lawyers will appeal to biological mitigators, and more juries will place defendants on the not-blameworthy side of the line.

It cannot make sense for culpability to be determined by the limits of current technology. A legal system that declares a person culpable at the beginning of a decade and not culpable at the end is not one in which culpability carries a clear meaning.

The heart of the problem is that it no longer makes sense to ask, “To what extent was it his

biology

and to what extent was it

him

?” The question no longer makes sense because we now understand those to be the same thing. There is no meaningful distinction between his biology and his decision making. They are inseparable.

As the neuroscientist

Wolf Singer recently suggested: even when we cannot measure what is wrong with a criminal’s brain, we can fairly safely assume that

something

is wrong.

23

His actions are

sufficient evidence

of a brain abnormality, even if we don’t know (and maybe will never know) the details.

24

As Singer puts it: “As long as we can’t identify all the causes, which we cannot and will probably never be able to do, we should grant that for everybody there is a neurobiological reason for being abnormal.” Note that most of the time we cannot measure an abnormality in criminals. Take

Eric Harris and

Dylan Klebold, the shooters at Columbine High School in Colorado, or

Seung-Hui Cho, the shooter at Virginia Tech. Was something wrong with their brains? We’ll never know, because they—like most school shooters—were killed at the scene. But we can safely assume there was

something

abnormal in their brains. It’s a rare behavior; most students don’t do that.

The bottom line of the argument is that criminals should always be treated as incapable of having acted otherwise. The criminal activity itself should be taken as evidence of brain abnormality, regardless whether currently measurable problems can be pinpointed. This means that the burden on neuroscientific expert witnesses should be left out of the loop: their testimony reflects only whether we currently have names and measurements for problems, not whether the problem exists.

So culpability appears to be the

wrong question to ask

.

Here’s the right question: What do we do,

moving forward

, with an accused criminal?

The history of a brain in front of the judge’s bench can be very complex—all we ultimately want to know is how a person is likely to behave in the future.

BRAIN-COMPATIBLE LEGAL SYSTEM

While our current style of punishment rests on a bedrock of personal volition and blame, the present line of argument suggests an alternative. Although societies possess deeply ingrained impulses for punishment, a forward-looking legal system would be more concerned with how to best serve the society from this day forward. Those who break the social contracts need to be warehoused, but in this case the future is of more importance than the past.

25

Prison terms do not have to be based on a desire for bloodlust, but instead can be calibrated to the risk of reoffending. Deeper biological insight into behavior will allow a better understanding of

recidivism—that is, who will go out and commit more crimes. And this offers a basis for rational and

evidence-based sentencing: some people need to be taken off the streets for a longer time, because their likelihood of reoffense is high; others, due to a variety of extenuating circumstances, are less likely to recidivate.

But how can we tell who presents a high risk of recidivism? After all, the details of a court trial do not always give a clear indication of the underlying troubles. A better strategy incorporates a more scientific approach.

Consider the important changes that have happened in the sentencing of sex offenders. Several years ago, researchers began to ask psychiatrists and parole board members how likely it was that individual sex offenders would relapse when let out of prison. Both the psychiatrists and the parole board members had experience with the criminals in question, as well as with hundreds before them—so predicting who was going to go straight and who would be coming back was not difficult.

Or wasn’t it? The surprise outcome was that their guesses showed almost no correlation with the actual outcomes. The psychiatrists and parole board members had the predictive accuracy of coin-flipping. This result astounded the research community, especially

given the expectation of well-refined intuitions among those who work directly with the offenders.

So researchers, in desperation, tried a more actuarial approach. They set about measuring dozens of factors from 22,500 sex offenders who were about to be released: whether the offender had ever been in a relationship for more than one year, had been sexually abused as a child, was addicted to drugs, showed remorse, had deviant sexual interests, and so on. The researchers then tracked the offenders for five years after release to see who ended up back in prison. At the end of the study, they computed which factors best explained the reoffense rates, and from these data they were able to build actuarial tables to be used in sentencing. Some offenders, according to the statistics, appear to be a recipe for disaster—and they are taken away from society for a longer time. Others are less likely to present a future danger to society, and they receive shorter sentences. When you compare the predictive power of the actuarial approach to that of the parole boards and psychiatrists, there is no contest: numbers win over intuitions. These

actuarial tests are now used to determine the length of sentencing in courtrooms across the nation.