Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation (15 page)

Read Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation Online

Authors: Elizabeth Pisani

The children asked me where I was going next and I pointed to the tiny island of Savu, which interrupts the expanse of sea to the east between Sumba and Timor. Then I swept my hand vaguely across a string of microscopic specks representing the islands which run in an arc from the edge of Timor, along the top of Australia, and all the way up to the tip of Indonesian Papua. I named one or two of the specks, then dried up. I had never been to these places, and had never met anyone else who had been to them, either. The kids snatched the map, squinted at the specks, and began to test me. ‘All right clever clogs, what island comes next to Kisar?’

We agreed to have a geography competition when I was next in Sumba, and that evening I walked around Waikabubak looking for a map to give them so that they could study. I could buy maps of the district of West Sumba, and even of NTT,

*

the province in which Sumba sits. But in all of Waikabubak there was not a map of the nation to be had. I asked the stony-faced Chinese traders in the general stores, expecting hands to be inserted into the dusty mountains of goods and a map to emerge, but no. Nothing in the bookshop, or in the town’s many stationery stores.

In Sumba, the nation didn’t exist.

*

The government classifies postings according to their location:

biasa, terpencil

and

sangat terpencil

, ordinary, remote and extremely remote. Salaries in extremely remote areas are nearly four times higher than in ordinary posts.

*

See Henrich et al., ‘In Cross-Cultural Perspective: Behavioral Experiments in 15 Small-Scale Societies’,

Behavioral and Brain Sciences

28, no. 6 (2005): 795–815.

*

Pronounced ‘En-tay-TAY’, short for

Nusa Tenggara Timur

, East Nusa Tenggara. Islanders joke bitterly that it stands for

Nusa Tertinggal Terus

: the Perpetually Neglected Islands.

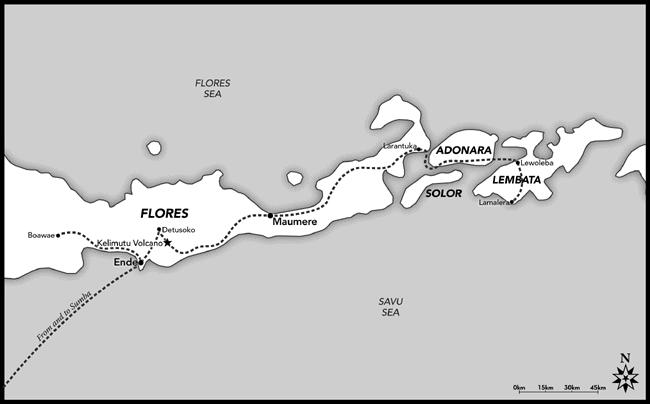

Map B: E

ASTERN

F

LORES AND

S

URROUNDING

I

SLANDS,

East Nusa Tenggara Province (NTT)

In the smaller islands of eastern Indonesia, people have a very intimate relationship with boats. Kerosene, eggs, rice, sugar: all come in on big cargo boats, whose frequency determines how much things will cost in the market. Ferries provide an escape route to the wider world. There are slow, uncomfortable, flat-bottomed car ferries for inter-island hops of twenty-four hours or less. Large passenger ferries run by the state firm Pelni chug from end to end of the archipelago on routes first laid down by the Dutch ‘steam-packets’. Islanders know each of these boats by name; in port towns, their timetables are engraved on the collective memory.

I planned to take the monthly Pelni ferry from Sumba’s eastern port of Waingapu across to tiny Savu. As far away as Waikabubak, a four-hour drive across Sumba on a road first built by Japanese troops during the occupation, people knew when the ferry was due. My West Sumba friends booked me into a share-taxi, making sure I would get to the boat on time.

But when we arrived at the port, there was no sign of the ship. ‘

Lagi doking, Bu

,’ the guard said amiably – it’s in dry dock for its annual repairs. ‘But it will be back in service next month.’ Further down the pier, a snort of Sumba ponies were being herded onto a car ferry, headed for Flores to the north-east of Sumba. I joined them, squeezing myself between the wheels of two trucks of sour-smelling seaweed. Besides the ponies, my fellow passengers included a cluster of gamblers and a single Brahmin cow with sad eyes, tethered near a big pile of grass. It was of accidents like this that my itinerary was made.

Animist Flores began turning Catholic when Portuguese missionaries settled here in the seventeenth century. Its coastal areas are dry compared with steamy Sumatra and lush Java, but the island’s vertebrae – a dozen active volcanoes – keep the uplands fertile enough. Together with the long, lacy borders of white sand on the island’s north-east coast, they provide some breathtaking scenery. In evenings the hills are shrouded with mist and life takes on a mystical air. On one such evening, walking into a valley near the tiny town of Detusoko, I stumbled on a group of women sitting in the river. A mother was holding her sarong over her chest for modesty’s sake, while her daughter scrubbed Mum’s back with a lathered stone. The women waved me over: ‘Come and bathe!’ ‘I don’t want to get cold,’ I yelled back, and one of the teenagers laughed and splashed me. The river water was hot. I had not had a hot shower since the start of the trip. I waded into the river fully clothed, and let the warmth bubble up around me, one of earth’s small luxuries.

I hadn’t guessed that the river might be hot because there was no sign of its having been turned into an

obyek wisata

, a ‘tourism object’. Though it sounds odd in English, ‘tourism objects’ lie at the core of Indonesian officialdom’s concept of the travel industry. Spectacularly beautiful waterfalls are turned into obyek wisata with the construction of cement tables and stools fashioned to look like cut pine trees. Pristine beaches are walled off behind pink concrete, broken only by a welcoming archway that proclaims ‘Welcome to Sunset Beach Tourism Object’! Hot springs get funnelled into slimy tiled baths hidden in rickety wooden sheds. Pathways through spectacular gorges are lined with vendors and littered with discarded drink cartons.

Central Flores seems miraculously to have escaped these horrors. About thirty kilometres from Detusoko is the Kelimutu volcano, one of Indonesia’s better-known natural wonders. I remembered it from an earlier visit in 1989; three lakes, one white, one green and one blood-red, nestled in a single giant crater. ‘The lakes have swapped colours now,’ said a nun at the convent I stayed at in Detusolo. This I had to see.

As I waited on the main road to flag down a bus, a young man sitting at a coffee stall offered to take me by

ojek

. An ojek is a motorcycle taxi, usually a smallish Honda or Yamaha scooter and often, in the poorer provinces of Indonesia, somewhat decrepit. Fine for getting around town, but for a journey of thirty kilometres on mountain roads to a volcano? No thanks. ‘Well, let me buy you a coffee then,’ the lad suggested. So I did. I was still drinking it as the bus rumbled past. I took the ojek.

The road snaked along the top of a deep valley. Rice terraces, bathed now in the kindly light of early morning, tumbled down to the river below. As he negotiated the bends in the road, Anton, the ojek driver, told me that his real interest was animal husbandry. He was almost ashamed to be offering lifts for money. ‘It’s not that I’m stupid, Miss, or lazy. I graduated from high school. But look around. I can’t afford to go to college, and what is there to do here except grow rice? It’s not like over there, in Java . . .’

Java, that mythical Other Country whose values Suharto had tried to etch across the nation. I asked Anton if he had ever been there. ‘What, to Java? Oh no . . .’ His tone was of awed disbelief, as if I’d asked if he had ever been to St Peter’s in Rome. Later, though, he mentioned that two of his brothers were working in Java. Couldn’t he go and live with them, go to college, pay his way by driving an ojek over there, just like he’s doing now? ‘But things are different there, Miss. It’s not like here.’ He swerved to avoid a huge bite-mark taken out of the road by a landslide, then laughed. ‘You see, you’d never have something like that in Java!’ Anton was worried, too, that he wouldn’t get into college ‘over there’, that he was too much of a hick. I gave him the standard ‘you’ll never know until you try / the worst that can happen is that you come back to doing what you are doing now’ pep talk.

For several months, Anton continued to send me the occasional ‘what’s up’ message, and I’d always reply. Then, nearly a year later, I got a surprise: ‘Hello Miss, where are you now? I’m in Surabaya.’ As it happened, the text came in as I was waiting for a flight to Surabaya, Java’s second largest city. We met for a coffee the following evening. Anton was in college, studying to become a vet. ‘I thought about what you said, and thought yes, she’s right. I can’t succeed unless I give it a go.’ Java turned out not to be as impossibly alien as he had feared. He still felt like a bit of a country bumpkin, he said, but there were other students from Flores who were showing him the ropes. ‘It’s better than sitting waiting for passengers in Detusoko.’

When Anton dropped me at Kelimutu – even the name sings – it was one of those heart-bursting days of glittering morning air and infinite vistas. The birds serenaded, the butterflies flirted, and I was all alone in one of the most beautiful places on earth. Two of Kelimutu’s lakes are divided by a single wall of jagged rock. One lake I remembered as being emerald green, the other a great pool of milk, The third, off at a distance, was sticky, oxidized blood. This time, though, the sibling lakes seemed to have bled into one another; they are now turquoise twins. As the clouds puffed in, smoky shadows flitted over their surface. I walked on up the dust-muffled path to the third lake, passing a solitary groundsman who was attacking the acres of scrub grass with a scythe the size of a Swiss Army knife. The blood lake, the one where locals believe old souls find their rest, had thickened almost to black. I wondered what had become of the souls of virgins and innocents now that the white lake where they used to seek refuge had morphed to blue. Geologists say these colour changes are the work of minerals burped up into the lakes from vents under the water. Though according to Kelimutu National Park’s official website, locals believe they are the spirits’ reaction to the election of a military candidate as president of Indonesia.

I sat for a while in a silence punctuated by birdsong and the occasional buzzing insect. It was mid-November, not high tourist season, but still, it seemed amazing that I could have this whole majestic scene entirely to myself. No busloads of rich kids from private schools in Java exploring the wonders of their nation. No groups of camera-clicking Japanese tourists with a niche interest in vulcanology. Not even any gap-year backpackers storing up exotic tales for fresher’s week at university in Manchester, San Francisco or Berlin. I was thrilled by the solitude, of course. But I felt almost offended on behalf of Indonesia.

There’s no doubt that Indonesia punches below its weight on the world stage. Just twenty-two athletes went from Indonesia to the Olympic Games in London in 2012 – not even one per ten million Indonesians. Though Indonesian soldiers were once popular as UN peacekeepers, very few Indonesians have made it to the top echelons of international organizations and none has ever headed one. No Indonesian has ever won a Nobel Prize.

*

The country had a higher profile when Sukarno (who spoke nine languages) roamed the world denouncing imperialism and wagged his finger at interfering neighbours. But Suharto, ever the yin to Sukarno’s yang, spoke little English and was uncomfortable in the international arena. He came out of his shell with his immediate neighbours; he was the driving force behind the establishment of ASEAN, the Association of South East Asian Nations, a sort of mutual support group for the not-very-democratic leaders of the region. But for three decades Suharto kept a low profile internationally, and Indonesians themselves did nothing to raise it.

Remarkably few Indonesians have chosen to settle in other countries. They do travel as contract labourers: in 2012, four million Indonesians trekked overseas to clean other people’s loos, weed their plantations and build their hotels, mostly in Saudi Arabia and Malaysia. But almost all of these people are on ‘package deal’ schemes; they are sent out in batches by government-approved agents and will be brought home when their contracts are up. This is not the sort of migration of which a diaspora is made, and it is a diaspora that spreads a country’s influence overseas.

I was mulling over the missing diaspora one night some years ago when I was out with my friend Luwi. Luwi is a well-educated upper-middle-class designer with a French grandfather, an international circle of friends and a well-stamped passport, exactly the sort of person who, if he were from Korea or Colombia, might have chosen to live in New York or Paris. It was four in the morning, and we were driving aimlessly around Jakarta in his blue Volkswagen beetle. I was rattling on about national identity. He looked over at me: ‘Are you hungry?’ As it happened, I was. ‘Me too.’ Within seconds we had pulled over at a pop-up street stall; a few minutes later we were sitting on a smooth palm-weave mat on the pavement with a freshly-made omelette and a glass of sweet ginger tea. I went back to my nationalist navel-gazing: why do so few Indonesians live overseas? One reason is that having studied or worked abroad carries great kudos in Indonesia; the social status and earning power it brings act as a magnet, pulling people home. But there’s another reason too, suggested by Luwi as he dolloped shrimp chilli on his omelette and gave a contented wave at our impromptu midnight feast: ‘How could you live without all this?’