Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation (22 page)

Read Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation Online

Authors: Elizabeth Pisani

The small building that declared itself to be the office of the department of transport was deserted. There was no one else around. I texted the harbour master in Kupang. ‘

Sabar, Bu

’, came the reply: ‘Be patient’. So I sat under a tree and read a book. After about an hour, a young man rocked up. He obviously wasn’t from Wini, so I asked if he was waiting for the boat. ‘There’s a boat? I haven’t seen anything at this dock in the two weeks I’ve been here.’

He was an engineer from Surabaya, sent to oversee the extension of that very dock. Why extend it if it’s never used? I asked. ‘

Proyek, kan

?’ ‘It’s a “project”, isn’t it?’

Noon came and went, then one o’clock, then two. I was beginning to think about Plan B when I saw a puff on the horizon. The puff turned into cloud and within just over an hour a huge, flat barge covered in green and blue tarpaulin was sitting alongside the pier. No one got off and I was the only new passenger to clamber up the ridged plank that was thrown from deck to dock.

I looked around at my fellow passengers. I had expected a dozen hardy souls, but the deck was packed; there must have been close to 300 people on board. Every square inch of deck space was taken up. People were hunkered down in fortresses built of boxes of electronics, rice sacks, stacks of eggs in square cardboard trays. There was no eye contact; the whole scene bristled with hostility. I made for a mouse-hole of about two foot by three foot behind a sack of garlic, but was warned off by a growling neighbour. The only empty space seemed to be on top of a warm, humming freezer. There, I unrolled my sleeping mat. Immediately, a terrier of a woman bore down, menacing me with a giant wooden spoon. One of the crew directed me back to the mouse-hole, to the fury of the growling neighbour.

Saumlaki, where I was headed, was five days away.

To my horror, I found that the territorial wars were reignited almost every time the ship stopped. As the harbour master had said, Perintis ships are cargo ships, and cargo is carried under decks. That meant that in most ports we pulled in at, in the blazing sunshine of midday or the dead of night, the tarpaulin that covered us was rolled back, the box-fortresses were deconstructed and sleeping mats rolled up, the passengers clambered down a plank onto the pier, and the whole deck of the ship was lifted up so that it could disgorge its contents.

The unloading stops ranged in length from a couple of hours to a whole day. But the instant the first section of deck went back down, the battle for territory began. Passengers old and new swarmed on board to occupy prize spots, oblivious to the sections of deck still swinging from ropes at neck height. There was much shouting. The crew shouted at passengers who were in danger of decapitation. The people who had already been on the ship for two days shouted at newcomers to establish prior possession. The newcomers shouted back to signal firmness of purpose. Families shouted instructions at one another as they created pincer movements, one brigade unfurling mats while the other built box-castles.

Over time, I got better at choosing a homeland and establishing sovereignty. I wanted to be far away from the twenty-four-hour karaoke at one end, but not too near the smelly loo at the other. A spot close to a ‘door’ – a gap in the side tarpaulin – provided breeze and a view, which is nice, but also lashings of rain, which is not. Tears in the tarpaulin overhead could turn a cosy spot into a puddle, too, so I had to keep an eye on the roof. Large families generally made bad neighbours – Indonesian kids are poorly disciplined and given to screaming. But I definitely didn’t want to be near the louts with the jerrycans of sopi palm wine, the boom boxes and the guitars.

A space along the side would allow me to move around relatively easily, but also meant that other people would be constantly trampling over my face. On day two I settled on a relatively quiet corner spot at the loo end, just next to the abyss leading to the cargo hold. It was in a dead end, so I was protected on two sides. I managed to hold on to it by making allies of an immobile old lady and her daughter.

They had come aboard at Liran island, where there was not even a pier. A long, skinny fishing boat had pulled up alongside our cargo ship, bobbing about while the daughter had hiked the older woman up from below. A boat boy grabbed from the deck above and after a bit of heave-ho, the old lady flopped on board. Her daughter scrambled up after her and I pulled them both into my buffer zone. After that, I did my best to shame the vulturing passengers into showing some respect for the elderly. It worked well enough.

Life on the boat settled into a rhythm of sorts. The prow of the ship, up by the anchor, was open to the heavens, a pleasant place for dawn musings. By nine in the morning the pitiless sun forced everyone back into the fetid air under the tarpaulin, the fug barely stirred by the slow flapping of improvised cardboard fans. In the late afternoon the sun sank behind us. This was the nicest time of day.

The evening light touched the water with flame and the dolphins came out to play. Every day they appeared, arching out of the water beside us, leaping and plunging, sometimes shooting vertically up and doing little pirouettes high in the air, just for the hell of it. Even the toughest of the sopi-drinking louts was carried away by the magic of the spectacle, pointing out the mother and child pairs, laughing with delight when a dolphin materialized within arm’s length of us. Then the light faded and the proper technicolor sunsets began, wispy pink surrounding soft greys in the clouds above, a cauldron of fire floating on the horizon below, the sea rippling glassy-dark to our bows. Inside, neon lights strung carelessly from the tarp-poles glared to life and the karaoke whined on, but here on the prow it was a calming time.

Five days is a long time to sit around on a boat, without even the lure of the beautiful actress from Mandarin, Miss Beautiful Lingling Zhou for distraction. I had planned to write dozens of letters, to read many worthy development reports, to Be Productive. But I found myself lulled into nothingness, a shameful amount of just staring into space, watching the light on the water, wondering idly whether to buy a plate of rice from the wooden-spoon-wielding terrier on board or wait for the next stop, at somewhere that may or may not be big enough to have a coffee stall.

The frequent stops gave me a chance to explore. In a seaside hamlet a retired soldier invited me in for strong coffee and a thick slab of home-made cake; he told me that things were getting better at the bottom of the armed forces but worse at the top. ‘We used to have smart generals and stupid soldiers,’ he said. ‘Now it’s the other way around; most of the troops have a decent education, but the cleverest graduates don’t want to go into the army any more.’

Sometimes these tiny islands yield the most unexpected things. In Kisar, where we stopped for a whole day, a fellow passenger, Harry, offered to show me the sights. On his motorbike, we buzzed down to the end of the island and looked across at East Timor, now a nation in its own right. We slowed down as instructed in front of the military barracks. (‘Nothing but trouble, those boys,’ said Harry, contradicting what I had heard from the retired soldier.) We stopped to look at the airstrip. And we went to visit Pak Hermanus, an ancient, hook-nosed gentleman who speaks only Oirata, a minority language even on the island of Kisar, and is said to belong to one of the Lost Tribes of Israel. A busybody Christian from Jakarta had whisked Hermanus off to the Holy Land the year before in the hope of hastening the Second Coming of Christ. Outside his palm-leaf house, ten rocks now sit dolloped together with cement like a giant turd: a monument to the Ten Lost Tribes. It was one of those little Ionesco moments that make travelling in Indonesia such a delight. Better yet: the acting Bupati of Southwest Maluku district recently said he wanted to turn Kisar into a destination for spiritual tourism because the island, all 10x10 kilometres of it, reminded him of Israel. Both countries are dry and mountainous, the Bupati pointed out, and there are sheep and goats in both places.

Several times, people in the towns we stopped in called me in off the streets and offered me the use of their bathroom so that I could scrub away the grime of the voyage. When I thanked people for the gifts of cake, companionship, cleanliness, they would wave me away. ‘Nonsense, nonsense. You’d do exactly the same for me over there!’ I knew it wasn’t true, and it made me all the more grateful. I swam in a deserted cove and sat in the cool of an old stone church. I bought an octopus off a fisherman and had it grilled in the island’s single dockside restaurant. Five days on a cargo boat wasn’t all bad.

There was a lot of chatting on the boat, of course; at each stop there were new people with new questions, many of which were answered for me by fellow passengers who had already mastered my back story. I, for my part, learned why people were making this long journey.

A lot of people were on their way to or from Kisar, the temporary seat of the Maluku Barat Daya (MBD) district government, to hand in a project proposal. One man I met, the brother of a sub-district head, had just collected payment for an illuminated Christmas tree he had built out of used water bottles outside the bupati’s office. Now he was submitting a proposal for Easter decorations.

Susun proposal

, to ‘put together a proposal’, was a phrase I had heard more frequently on this trip than in the previous two decades put together. I heard it from NGOs, of course, but also from priests, students, farmers, teachers, village women’s groups, policemen and dozens more. These days, everybody in Indonesia seems to be proposing to squeeze small (and sometimes not so small) amounts of money out of the newly flush local governments.

The immobile old lady in my buffer zone was not putting together a proposal. She was going to hospital; her legs had swollen up and she couldn’t walk properly. There was no hospital in Liran, nor should there be; the island has one village with a population of around 800 people. It does have a primary and a middle school, and a satellite health post staffed by a local lady with some training as a midwife, ‘but all she has to offer are pills you can buy at the kiosk’. There was no hospital anywhere else in Southwest Maluku either, though the newly designated district capital was allocated a knock-down field hospital six months later.

In terms of transport time, the nearest hospital was in Kupang, the capital of NTT, a day and a half away. But this frail old lady couldn’t go there, because Liran is in Maluku province, so her health card, which gives her cheaper treatment, wasn’t valid in Kupang. So she sat stoically for three days and three nights to get to hospital in Saumlaki. Even there, she would have to pay a bribe to be seen. Now that Southwest Maluku has gone its own way as a district, the hospital in Saumlaki was no longer supposed to accept health cards from Liran.

If she were to do things by the book, this sick seventy-something-year-old would have to travel another three days to the provincial capital of Ambon. ‘But if you know people from the old days, you can usually fix it,’ the old lady said.

*

A

bupati

is the head of a largely rural district, known as a

kabupaten

. Urban districts are known as

kota

, and are headed by a

walikota

or mayor. When I am speaking in general terms rather than about a specific individual, bupati can be assumed also to refer to walikota.

*

In fact, several districts can lay claim to this title, depending on which measure of poverty is used. While Savu scores poorest on every one of these measures in the province of NTT, there are some pretty desolate pockets scattered among the mineral riches in Papua, as well as in Maluku.

*

In Indonesian, the ‘Four D’s’:

Datang

,

Duduk

,

Diam

,

Duit

.

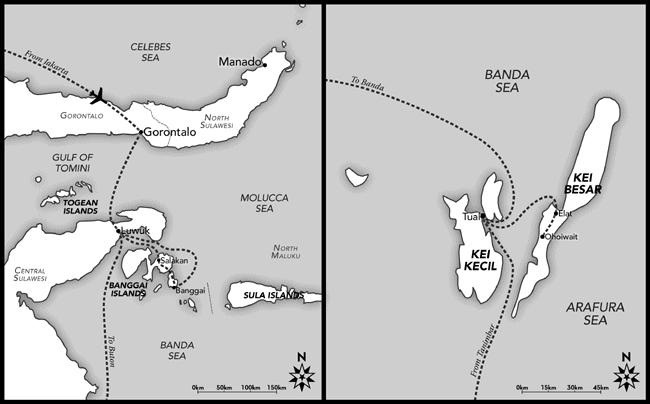

Map D: B

ANGGAI

I

SLANDS

, Central Sulawesi

Map E: K

EI

I

SLANDS

, Maluku

It was coming up to Christmas 2011, and I was wandering up through the south-eastern islands of Maluku with only the Victorian beetle-collector Alfred Wallace for company. Wallace had spent the Christmas of 1857 on a ship close to where I now was, and he had been unhappy. ‘The captain, though nominally a Protestant, seemed to have no idea of Christmas Day as a festival,’ he complained. ‘Our dinner was of rice and curry as usual, and an extra glass of wine was all I could do to celebrate it.’

It was an unusually morose note in an otherwise chirpy description of the bottom right-hand corner of the archipelago, the bits just next to the giant island of New Guinea. Wallace was especially taken by the Kei islanders, who streamed uninvited onto his ship to the dismay of his buttoned-up Javanese and Malay crew:

These Ke men came up singing and shouting, dipping their paddles deep in the water and throwing up clouds of spray . . . They seemed intoxicated with joy and excitement . . . [The crew] reminded me of a party of demure and well-behaved children suddenly broken in upon by a lot of wild, romping, riotous boys, whose conduct seems most extraordinary and very naughty.

*