Introducing the Honourable Phryne Fisher (18 page)

Read Introducing the Honourable Phryne Fisher Online

Authors: Kerry Greenwood

CHAPTER ONE

A sad tale’s best for Winter

Shakespeare

The Winter’s Tale

Candida Alice Maldon was being a bad girl. Firstly, she had not told anyone that she had found a threepence on the street. Secondly, she had not mentioned to anyone in the house that she was going out, because she knew that she would not be allowed. Thirdly, since she had lost one of her teeth, she was not supposed to be eating sweets, anyway.

The consciousness of wrongdoing had never stopped Candida from doing anything she wanted. She was prepared to be punished, and even prepared to feel sorry. Later. She approached the sweet-shop counter, clutching her threepence in her hand, and stared at the treasures within. Laid out, like those Egyptian treasures her father had shown her photos of in the paper, were sweets enough to give the whole world toothache.

There were red and green toffee umbrellas and toffee horses on a stick. There were jelly-beans and jelly-babies and snakes in lots of colours, and lolly bananas and snowballs and acid drops. These had the advantage that they were twenty-four a penny, but they were too sour for Candida’s taste. She dismissed wine-gums as too gluey and musk sticks as too crumbly, and humbugs as too peppery. She considered boiled lollies in all the colours of the millefiore brooch which her grandmother wore, and barley-sugar in long, glassy canes. There were ring sticks with real rings around them, and rainbow balls and honeybears and chocolate toffs. Candida breathed heavily on the glass and wiped it with her sleeve.

‘What would you like, dear?’ asked the shopkeeper.

‘My name is Candida,’ the child informed her, ‘and I have threepence. I would like a ha’porth of honeybears, a ha’porth of coffee buds, a ha’porth of mint-leaves, a ha’porth of silver sticks . . . a ha’porth of umbrellas and a ha’porth of bananas.’

‘There you are, Miss Candida,’ said the shopkeeper, accepting the sweaty, warm coin. ‘Here are your lollies. Don’t eat them all at once!’

Candida walked out of the shop, and began to trail her way home. She was not in a hurry because no one knew she was gone.

She was hopping in and out of the gutter, as she had been expressly forbidden to do, when a car drew up beside her. It was a black car shaped like a beetle. Nothing like her father’s little Austin. Candida looked up with a start.

‘Candida! There you are! Your daddy sent me to look for you. Where have you been?’ A woman opened the car door and extended a hand.

Candida stepped closer to look. The woman had yellow hair and Candida did not like her smile.

‘Come along now, dear. We’ll take you home.’

‘I don’t believe you,’ Candida said clearly. ‘I don’t believe my daddy sent you. I shall tell him you’re a liar,’ and she jumped back onto the pavement to run home. But someone in the back of the car was too quick. She was seized by strong hands and an odd-smelling handkerchief was clamped over her face. Then the world went dark green.

Phryne Fisher was enduring afternoon tea at the Traveller’s Club with Mrs William McNaughton for a special reason. This did not make the ordeal any more pleasant, but it gave her the necessary spinal fortitude. Not that there was anything wrong with the tea. There were scones and strawberry jam with cream obviously obtained from contented cows. There were

petit fours

in delightful colours and brandy snaps. There was Ceylon tea in the big silver teapot, and fine Chinese cups from which to drink it.

The only fly in the afternoon’s ointment was Mrs William McNaughton. She was a pale, drooping woman, dressed in an unbecoming grey. Her sheaf of pale hair was coming adrift from its pins. These disadvantages could have been overcome with the correct choice of hairdresser and

couturière,

but the essential soppiness of her character was irreparable. Mrs William McNaughton reminded Phryne of jelly-cake and aspens and other quivering things, but there was steel under her flinching. This was a woman who had all the marks of extensive abuse: the hollow eyes, the nervous movements, the habit of starting at a sudden sound. But she had survived in her own way. She might cower, but she would not release hold of an idea once she had grasped it, and she could keep a secret or embark on a clandestine path. Her concealment of her character and her desires would be close to absolute, and torture would not break her now if her past had not killed her. However, despite the reasons, Phryne could not like her. Phryne herself met all challenges head-on, and the Devil take the hindmost.

‘It’s my son, Miss Fisher,’ said Mrs McNaughton, handing Phryne a cup of tea. ‘I’m worried about him.’

‘Well, what worries you?’ asked Phryne, pouring her cup of anaemic tea into the slop-bowl and filling it with a stronger brew. ‘Have you spoken to him about it?’

‘Oh, no!’ Mrs McNaughton recoiled. Phryne added milk and sugar to her tea and stirred thoughtfully. The process of finding out what was bothering McNaughton was like extracting teeth from an uncooperative ox.

‘Tell me, then, and perhaps I may be able to help,’ she suggested.

‘I have heard of your talents, Miss Fisher,’ observed Mrs McNaughton artlessly. ‘I hoped that you might be able to help me without causing a scandal. Lady Rose speaks very highly of you. She’s a connection of my mother’s, you know.’

‘Indeed,’ agreed Phryne, taking a brandy snap and smiling. Lady Rose had mislaid her emerald earrings, and was positive that her maid of long standing had not stolen them, thus contradicting her greedy nephew and heir, as well as the local policeman. She had hired Phryne to find the earrings, and this Phryne had done in one afternoon’s inquiry among the local

Montes de Piété,

where the nephew had pawned them. He had made an unwise investment in the fourth at Flemington, putting the proceeds on a horse which was possessed of insufficient zeal and had not been able to redeem them. Lady Rose had been less than generous with the fee, but more than generous with her recommendations. Since Phryne did not need the money, she was pleased with the bargain. Lady Rose had told her immediate acquaintance that, ‘She may look like a flapper—she smokes cigarettes and drinks cocktails and I believe that she can fly an aeroplane—but she has brains and bottom, and I thoroughly approve of her.’

Since she had made the decision to become an investi- gator, Phryne had not been out of work. She had found the Persian kitten for which the little son of the Spanish ambassador was pining. It had been seduced by the delights of the nearby fish-shop’s storehouse, and had been shut in. Phryne had released it, and (after it had suffered three baths) it was restored to its doting admirer. She had worked three weeks in an office, watching a costing clerk skimming the warehouse and blaming the shortfall on the inefficiency of a female stores clerk. Phryne had taken a certain delight in catching that one. She had watched a brutal and violent husband for long enough to obtain sufficient evidence for his battered wife to divorce him. For, in addition to her bruises and broken fingers, she needed to prove adultery. Phryne, who never shrank from a little bending of the rules, had provided the adulterer with a suitable partner from among the working girls of her acquaintance, and had paid the photographer’s fee out of her own bounty. The husband was informed that the negatives would be handed over after the delivery of the decree absolute, and everyone wondered that such a determined and hard man went through his divorce like a lamb. His divorced wife was in possession of a comfortable competence and was reported to be very happy.

The result of all this work was that Phryne, to her surprise, was busy and occupied and had not been bored for months. She considered that she had found her

métier.

Physically, Phyrne had been described by the redoubtable Lady Rose as ‘small, thin, with black hair cut in what I am told is a bob, disconcerting grey-green eyes and porcelain skin. Looks like a Dutch doll’. Phryne admitted this was a fair depiction.

For the interview with Mrs McNaughton, she had selected a beige dress of mannish cut, which she felt made her look like the directress of a women’s prison, and matching taupe shoes and stockings. Her cloche hat was of a quiet dusty pink felt.

She was not getting anywhere with Mrs McNaughton, who had sounded frantic on the phone, but who now seemed unable to get to the point. Phryne bit into the brandy snap and waited.

Mrs McNaughton (who had not asked Phryne to call her Frieda) took a gulp of her watery tea and finally blurted out what was on her mind. ‘I’m afraid my son is going to kill my husband!’

Phryne swallowed her brandy snap with some difficulty. This was not what she had been expecting.

‘Why do you think that?’ asked Phryne, calmly.

Mrs McNaughton felt inside her large knitting bag, which had reposed on the sofa beside her, and handed Phryne a crumpled letter. It looked like it had been retrieved from the fire, for it was singed at one edge.

Phryne unfolded it carefully, as the paper was brittle.

‘If the pater doesn’t come to the party, it will be all up,’ she read aloud. ‘Might have to remove him. Anyway, I am going to talk to him about it tonight, so wish me luck, kid.’ It was signed, ‘Yours as ever, Bill.’

‘You see?’ whispered Mrs McNaughton. ‘He means to kill William. What am I to do?’

‘Where did you find this?’ asked Phryne. ‘In the grate, was it?’

‘Yes, how clever of you, Miss Fisher. My maid found it this morning when she was doing the rooms, it’s a carbon copy. Bill always keeps carbons of his letters. He’s so business-like. He made a special arrangement to talk to William in the study tonight about this new venture, and I,’ Mrs McNaughton’s voice wavered, ‘don’t know what to do.’

‘Remove could have other meanings than murder, Mrs McNaughton. What sort of venture?’

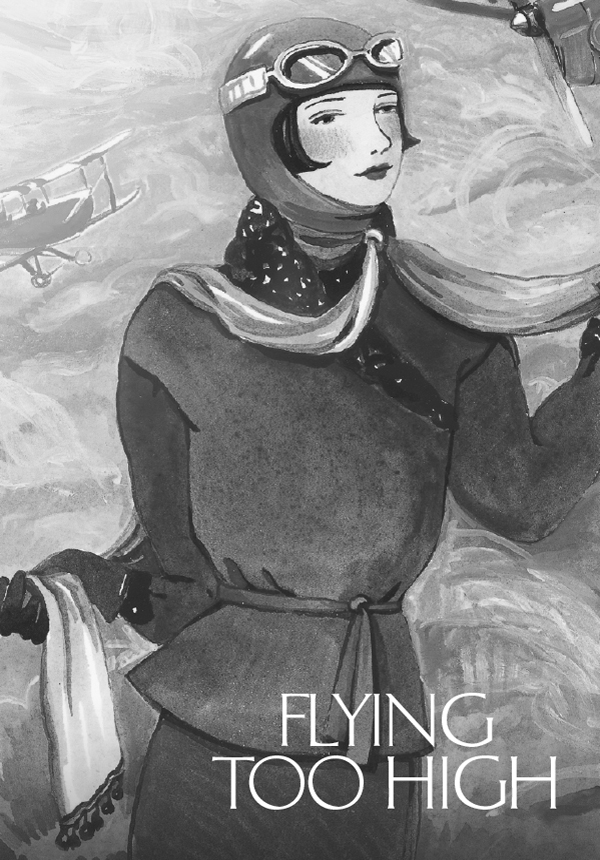

‘Something to do with aeroplanes. Bill is a pilot, you know, and has won all sorts of races and things. It’s so worrying for a mother, Miss Fisher, having him flying. Those planes don’t look strong enough to stay up in the sky, and I don’t really believe they can, you know, being heavier than the air. He conducts a school at Essendon, Miss Fisher, teaching people to fly. But he wants capital from William for a new venture.’

‘And what is that?’ asked Phryne, interested. She loved planes.

‘They want to fly over the South Pole—apparently the North Pole is old hat. “No one has tried planes down here,” he said to me. “It’s no use staying on the ground. It’s all ice and desert, but in the air we can cover miles in minutes.” And he wants William to put money into it.’

‘And your husband does not agree?’

‘He won’t do it. They’ve had some terrible fights about money. William put up the capital to start the flying school, and it hasn’t been going well. He insisted that he be chairman of directors of the company, and he has all the books brought to him every month, then he calls Bill in and they have an awful argument about how the business is going. He was furious about the purchase of the new plane.’

‘Why?’

‘He says that a company with such a cash problem can’t extend on capital—at least I think that’s what he said. I don’t know any of these business terms, I’m afraid. They are both big, hot tempered men with strong opinions—they are very like each other—and they have been fighting since Bill was born, it seems,’ said Mrs McNaughton with suprising shrewdness. ‘Amelia escaped a lot of it because she’s a girl, and William does not expect anything of girls. Anyway she’s dabbling in art at the moment, and she’s hardly ever here. She wanted an allowance to go and live in a studio, but William put his foot down about that. “No daughter of mine is going to live like a Bohemian,” he said, and wouldn’t give her any money, but she enrolled in the gallery school against his wishes and she only comes home to sleep. She’s no trouble,’ said Mrs McNaughton, dismissing her daughter with a wave of her teacup. ‘But Bill clashes. He disagrees with William to his face. I don’t think they’ll ever get on, and they behave as though they hate one another. Nothing but noise and shouting, and my nerves can’t bear much more. I’ve already had to go to Daylesford for the waters. I’m afraid that Bill will lose his temper and . . . and . . . do what he threatened, Miss Fisher. Can’t you do something?’

‘What would you like me to do?’

‘I don’t know,’ wailed Mrs McNaughton. ‘Something!’

It appeared that she had relied on Phryne to wave a magic wand. As her hostess appeared to be on the verge of the vapours, Phryne made haste to assent. ‘Well, I’ll try. Where is Bill now?’

‘He’ll be at the airfield, Miss Fisher. The Sky-High Flying School. It’s the red hangar at Essendon. You can’t miss it.’

‘I’ll go there now,’ said Phryne, putting down her cup. ‘And I don’t think you have any reason to be really upset, Mrs McNaughton. I think “remove” means “remove him from the board of directors” not “remove him from this world”. But I’ll talk to Bill, anyway.’

‘Oh, thank you, Miss Fisher,’ said Mrs McNaughton, fumbling for her smelling salts.

. . .

Phryne started the Hispano-Suiza, which was her pride and dearest possession, and sped back to the Windsor Hotel. She had found a house and was moving out, and hoped that her new home would be as comfortable as the hotel. The Windsor had everything Phryne needed: style, comfort and room service. She parked her car and ran up the stairs.

‘Dot, do you want to come for a ride in a plane?’ called Phryne from the bathroom to her invaluable and devoted maid. Dot, who had come by way of attempted manslaughter into Phryne’s service, was a conservative young woman who had so far resisted the temptation to bob her long brown hair. She was a slim, plain girl and was wearing her favourite brown overall. Dot did not like the idea of the Hispano-Suiza, and the thought of being bodily hauled through the firmament, which should contain only birds and angels, did not appeal to her. She went to the bathroom door with a leather flying jacket over her arm.

‘No, Miss. I don’t want a ride in a plane.’

‘All right, ’fraidy cat. What are you doing this afternoon? Want to come and watch, or have you something interesting to do?’

‘I’ll come and watch, Miss, but just don’t ask me to go up in one of them things. Here’s your breeches, and the leather coat. What about a hat, Miss?’