Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (29 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Herrera was said to have fallen out with Allodi, and was being courted by Real Madrid; Suárez was reported also to be considering a return to Spain, the homeland of his fiancée; and Moratti was believed to be keen to give up the presidency to devote more time to his business interests. Worse, Suárez was ruled out of the final with what was variously described as a thigh strain or cartilage damage, while Mazzola had suffered flu in the days leading up to the game.

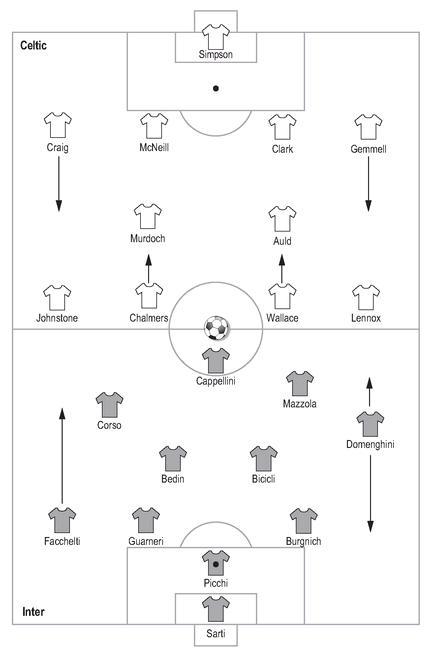

Celtic had dabbled with a defensive system, away to Dukla Prague in the semi-final, but although they got away with a goalless draw, that game had made clear that their strength was attacking. Their basic system was the 4-2-4 that had spread after the 1958 World Cup, but the two centre-forwards, Stevie Chalmers and Willie Wallace, took turns dropping deep, trying to draw out Inter’s central defensive markers. The two wingers, Jimmy Johnstone and Bobby Lennox, were encouraged to drift inside, creating space for the two attacking full-backs, Jim Craig and Tommy Gemmell. If Inter were going to defend, the logic seemed to be, Celtic were going to attack with everything in their power.

And Inter were set on defending, particularly after Mazzola gave them a seventh-minute lead from the penalty spot. They had done it against Benfica in 1965, and they tried to do it again, but this was not the Inter of old. Doubts had come to gnaw at them, and as Celtic swarmed over them they intensified. ‘We just knew, even after fifteen minutes, that we were not going to keep them out,’ Burgnich said. ‘They were first to every ball; they just hammered us in every area of the pitch. It was a miracle that we were still 1-0 up at half-time. Sometimes in those situations with each minute that passes your confidence increases and you start to believe. Not on that day. Even in the dressing room at half-time we looked at each other and we knew that we were doomed.’

For Burgnich, the

ritiro

had become by then counter-productive, serving only to magnify the doubts and the negativity. ‘I think I saw my family three times during that last month,’ he said. ‘That’s why I used to joke that Giacinto Facchetti, my room-mate, and I were like a married couple. I certainly spent far more time with him than my wife. The pressure just kept building up; there was no escape, nowhere to turn. I think that certainly played a big part in our collapse, both in the league and in the final.’

On arriving in Portugal, Herrera had taken his side to a hotel on the sea-front, half an hour’s drive from Lisbon. As usual, Inter booked out the whole place. ‘There was nobody there, except for the players and the coaches, even the club officials stayed elsewhere,’ Burgnich said. ‘I’m not joking, from the minute our bus drove through the gates of the hotel to the moment we left for the stadium three days later we did not see a single human being apart from the coaches and the hotel staff. A normal person would have gone crazy in those circumstances. After many years we were somewhat used to it, but by that stage, even we had reached our breaking point. We felt the weight of the world on our shoulders and there was no outlet. None of us could sleep. I was lucky if I got three hours a night. All we did was obsess over the match and the Celtic players. Facchetti and I, late at night, would stay up and listen to our skipper, Armando Picchi, vomiting from the tension in the next room. In fact, four guys threw up the morning of the game and another four in the dressing room before going out on the pitch. In that sense we had brought it upon ourselves.’

Celtic, by contrast, made great play of being relaxed, which only made Inter feel worse. In terms of mentality, it was

catenaccio

’s

reductio ad absurdum

, the point beyond which the negativity couldn’t go. They had created the monster, and it ended up turning on its maker. Celtic weren’t being stifled, and the chances kept coming. Bertie Auld hit the bar, the goalkeeper Giuliano Sarti saved brilliantly from Gemmell, and then, seventeen minutes into the second half, the equaliser arrived. It came thanks to the two full-backs who, as Stein had hoped, repeatedly outflanked Inter’s marking. Bobby Murdoch found Craig on the right, and he advanced before cutting a cross back for Gemmell to crash a right-foot shot into the top corner. It was not, it turned out, possible to mark everybody, particularly not those arriving from deep positions.

The onslaught continued. ‘I remember, at one point, Picchi turned to the goalkeeper and said, “Giuliano, let it go, just let it go. It’s pointless, sooner or later they’ll get the winner,”’ Burgnich said. ‘I never thought I would hear those words, I never imagined my captain would tell our keeper to throw in the towel. But that only shows how destroyed we were at that point. It’s as if we did not want to prolong the agony.’

Inter, exhausted, could do no more than launch long balls aimlessly forward, and they succumbed with five minutes remaining. Again a full-back was instrumental, Gemmell laying the ball on for Murdoch, whose mishit shot was diverted past Sarti by Chalmers. Celtic became the first non-Latin side to lift the European Cup, and Inter were finished.

Worse followed at Mantova. As Juventus beat Lazio, Sarti allowed a shot from Di Giacomo - the former Inter forward - to slip under his body, and the

scudetto

was lost. ‘We just shut down mentally, physically and emotionally,’ said Burgnich. Herrera blamed his defenders. Guarneri was sold to Bologna and Picchi to Varese. ‘When things go right,’ the sweeper said, ‘it’s because of Herrera’s brilliant planning. When things go wrong, it’s always the players who are to blame.’

As more and more teams copied

catenaccio

, its weaknesses became increasingly apparent. The problem Rappan had discovered - that the midfield could be swamped - had not been solved. The

tornante

could alleviate that problem, but only by diminishing the attack. ‘Inter got away with it because they had Jair and Corso in wide positions and both were gifted,’ Maradei explained. ‘And, also, they had Suárez who could hit those long balls. But for most teams it became a serious problem. And so, what happened is that rather than converting full-backs into

liberi

, they turned inside-forwards into

liberi

. This allowed you, when you won possession, to push him up into midfield and effectively have an extra passer in the middle of the park. This was the evolution from

catenaccio

to what we call “

il giocco all’ Italiano

” - “the Italian game”.’

Internazionale 1 Celtic 2, European Cup Final, Estadio Nacional, Lisbon, 25 May 1967

In 1967-68, morale and confidence shot, Inter finished only fifth, thirteen points behind the champions Milan, and Herrera left for Roma.

Catenaccio

didn’t die with

la grande Inter

, but the myth of its invincibility did. Celtic had proved attacking football had a future, and it wasn’t just Shankly who was grateful for that.

Chapter Eleven

After the Angels

∆∇ The World Cup in 1958 was, in a very different way, just as significant in shaping the direction of Argentinian football as it had been for Brazilian. Where for Brazil success, and the performances of bright young things such as Pelé and Garrincha, confirmed them in their individualist attacking ways, for Argentina a shocking failure left them questioning the fundamentals that had underpinned their conception of the game for at least three decades. Tactical shifts tend to be gradual, but in this case it can be pinpointed to one game: the era of

la nuestra

ended with Argentina’s 6-1 defeat to Czechoslovakia in Helsingborg on 15 June 1958.

The change in the offside law in 1925 had passed all but unnoticed in Argentina, and an idealistic belief in 2-3-5 - or, perhaps more accurately, simply in playing, for the notion that there could be another way seems never to have occurred - carried them right through until Renato Cesarini took charge of River Plate in 1939. Even the Hungarian Emérico Hirschl, who arrived at Gimnasia de la Plata in 1932 and moved to River in 1935, and was accused of importing European ideas, seems to have favoured a classic Danubian pyramid, although probably by then with withdrawn inside-forwards. Certainly his philosophy was an attacking one, as a record 106 goals in thirty-four games in the double championship-winning year of 1937 indicates. Cesarini played in that side, but it was after he had succeeded Hirschl that River reached their peak.

Cesarini was one of the original

oriundi

, who left Argentina for Italy in the late 1920s. He had been born in Senigallia, Italy, in 1906, but his family emigrated to Argentina when he was a few months old. He began his playing career with Chacarita Juniors, but, in 1929, Juventus enticed him back to the land of his birth. He was spectacularly successful there, winning five consecutive Serie A titles and developing such a knack of scoring crucial late goals that even now in Italy last-minute winners are said to have been scored in the

zona cesarini

.

Juve developed the

metodo

at roughly the same time as the national coach Vittorio Pozzo, but Cesarini had a very specific role in it, often man-marking the opponents’ most creative player. Not surprisingly, when he returned to Argentina in 1935 - initially as a player with Chacarita, and then with River - he brought those ideas with him. Cesarini is often described as having introduced the W-M to Argentina, but, like Dori Kürschner in Brazil, his version of it would not have been recognised as such in Britain. Rather what he brought was the

metodo

, as he deployed Néstor Rossi, a forward-thinking centre-half, slightly deeper than the wing-halves, in the manner of Luisito Monti (himself, of course, an

oriundo

). Although Rossi had to provide defensive cover, the ‘Howler of the Americas’ - as fans dubbed him for the ferocity of his organisational shouting - was also expected to initiate attacks. ‘Rossi was my idol,’ said the great holding midfielder Antonio Rattín, who was Argentina’s captain at the 1966 World Cup. ‘I tried to do everything Rossi did. Not just the way he played, but the way he yelled, the way he moved, the way he did everything. My first game for Boca Juniors was against River. I was nineteen, he was thirty-one. The first thing I did after that first match, which we won 2-1, was to get a picture with him.’

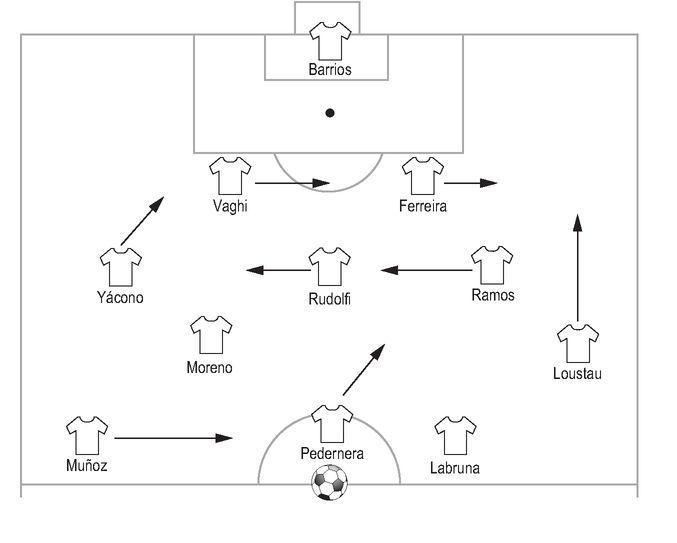

From the late twenties, inside-forwards in both Uruguay and Argentina had begun pulling deep from the front line, but under Cesarini, River took such movement to extremes. The front five of - reading from right to left - Félix Loustau, Ángel Labruna, Adolfo Pedernera, José Moreno and Juan Carlos Muñoz became fabled (although they only played as a quintet eighteen times over a five-year period). Rather than the two inside-forwards withdrawing, it was Moreno and Pedernera who dropped off into the space in front of the half-line. Loustau, meanwhile, patrolled the whole of the right flank, becoming known as a ‘

ventilador-wing

’ - ‘fan-wing’ (‘

puntero-ventilador

’ is used, but the half-English term seems more common) - because he was a winger who gave air to the midfield by doing some of their running for them.

La Máquina

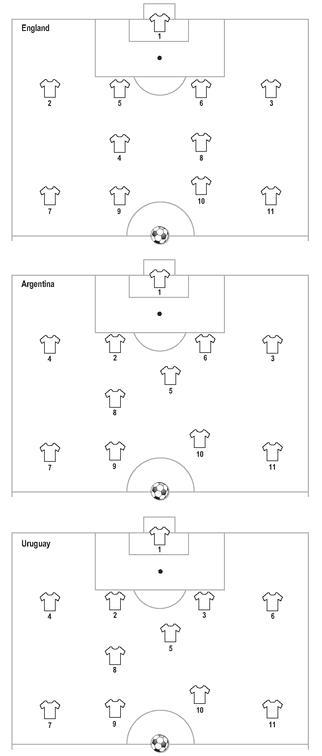

Loustau’s running meant that Norberto Yácono, the nominal right-half, could be given a more defensive brief, and he became known as ‘The Stamp’ for the way he would stick to the player he was marking. (Everybody and everything at the time, it seems, had nicknames, an indication perhaps of how central football was to popular culture and everyday conversation in Argentina at the time.) As other teams replicated Yácono’s role, Argentinian football gradually developed what was effectively a third-back, but rather than it being the centre-half, the No. 5, dropping in between the two full-backs (Nos. 2 and 3), it was the right-half, the No. 4, operating to the right of them. When 4-2-4 was adopted in the aftermath of 1958, it was - as elsewhere - the left-half, the No. 6, who moved back into a central defensive position, alongside the No. 2 and with the No. 3 to his left, while the centre-half, the No. 5, remained as a holding midfielder. (Even today in Argentina, positions tend to be known by their numbers, so Rattín, for instance, was a ‘five’, while Osvaldo Ardiles was an ‘eight’.) So, where a typical English back four would read, from right-to-left, 2, 5, 6, 3, an Argentinian one would read 4, 2, 6, 3.

In Uruguay, meanwhile, where there was no corresponding movement of the right-half backwards, and so no consequent shuffle of the two full-backs to the left. When the 2-3-5 (or the

metodo

) became 4-2-4, the two wing-halves simply dropped straight in as wide defenders (what would in Britain today be called full-backs), and a back-four there would read, 4, 2, 3, 6, although the 2 would often - as Matías González had in the 1950 World Cup final - play behind the other three defenders as a sweeper, thus replicating the numbering system in the Swiss

verrou

.

Cesarini’s River side,

la Máquina

, became the most revered exponents of

la nuestra

. ‘You play against

la Máquina

with the intention of winning,’ said Ernesto Lazzatti, the Boca Juniors No. 5, ‘but as an admirer of football sometimes I’d rather stay in the stands and watch them play.’ As befits the self-conscious romanticism of the Argentinian game at the time, though, River were not relentless winners. Although they were, by general consent, the best side in the country, between 1941 and 1945 River won just three titles, twice finishing second to Boca. ‘They called us the “Knights of Anguish” because we didn’t look for the goal,’ said Muñoz. ‘We never thought we couldn’t score against our rivals. We went out on the pitch and played our way: take the ball, give it to me, a

gambeta

, this, that and the goal came by itself. Generally it took a long time for the goal to come and the anguish was because games were not settled quickly. Inside the box, of course, we wanted to score, but in the midfield we had fun. There was no rush. It was instinctive.’

La Máquina

was a very different machine to that of Herbert Chapman’s Arsenal.

Numbering in the 4-2-4

As such, they were the perfect representatives of the Argentinian golden age, when football came as close as it ever would to Danny Blanchflower’s ideal of the glory game. Isolation - brought about by war and Perónist foreign policy - meant there were no defeats to international sides to provoke a re-think, and so Argentinian football went ever further down the road of aestheticism.

It may have been insular, but that is not to say that the impression of superiority was necessarily illusory. On the odd occasion when foreign opposition was met, it tended to be beaten. Over the winter of 1946-47, for instance, San Lorenzo toured the Iberian peninsular, playing eight games in Spain and two in Portugal. They won five, lost just once, and scored forty-seven goals. ‘What would have happened if Argentina had played in the World Cup at that time?’ asked the forward René Pontoni. ‘I feel like I have a thorn stuck in my side that has not gone away over the years. I don’t want to be presumptuous, but I believe that if we’d been able to take part, we’d have taken the laurels.’

Victory in the representative game over England in 1953 seemed only to confirm what everybody in Argentina had suspected: that their form of the game was the best in the world, and that they were the best exponents of it. Who, after all, was leading Real Madrid’s domination of the European Cup but Alfredo di Stéfano, brought up in the best traditions of

la nuestra

at River? That conclusion was corroborated as Argentina won the Copa América in 1955 and retained it in Peru two years later.

That latter side bubbled with young talent, the forward-line of Omar Corbatta, Humberto Maschio, Antonio Angelillo, Omar Sívori and Osvaldo Cruz playing with a mischievous verve that earned them the nickname ‘The Angels with Dirty Faces’. They scored eight against Colombia, three against Ecuador, four against Uruguay, six against Chile and three against Brazil. They lost their final game to the hosts, but by then the title was won and Argentina’s isolation emphatically over. They weren’t just back: they were the best side in South America, and possibly the world.

By the time of 1958 World Cup, though, Maschio, Angelillo and Sívori had moved to Serie A, and all three ended up playing international football for Italy. Di Stéfano, similarly, had thrown in his lot with Spain. Come Sweden, Argentina were so desperate for forwards that for cover they were forced to turn to Labruna, who was by then approaching his fortieth birthday. A 3-1 defeat to the defending champions West Germany was no disgrace, but it did suggest Argentina weren’t quite as good as they had believed themselves to be. ‘We went in wearing a blindfold,’ Rossi admitted.

Still, self-confidence was restored as they came from behind to beat Northern Ireland 3-1 in their second game. They ended with party-pieces - ‘taking the mickey’ said the Northern Ireland midfielder Jimmy McIlroy - but the warning signs were there. Northern Ireland had been told of Argentina’s great tradition, of the skill and the pace and the power of their forward play, but what they found, McIlroy said, was ‘a lot of little fat men with stomachs, smiling at us and pointing and waving at girls in the crowd’.

That left Argentina needing a draw in their final group game against Czechoslovakia to progress. Czechoslovakia didn’t even make it to the quarter-finals, losing in a playoff to Northern Ireland, but they blew Argentina away. ‘We were used to playing really slowly, and they were fast,’ said José Ramos Delgado, who was in the squad for the tournament but didn’t play. ‘We hadn’t played international football for a long time, so when we went out there we thought we were really talented, but we found we hadn’t followed the pace of the rest of the world. We had been left behind. The European teams played simply. They were precise. Argentina were good on the ball, but we didn’t go forwards.’

Milan Dvorák put Czechoslovakia ahead after eight minutes with an angled drive, and before half-time Argentina were three down as individual errors handed two goals to Zdenek Zikán. Oreste Corbatta pulled one back from the penalty spot, but Jiri Feureisl had restored the three-goal margin within four minutes, before two late strikes from Václav Hovorka completed a 6-1 humiliation.