Iran: Empire of the Mind (40 page)

The Rule of Mohammad Reza Shah and the White Revolution

The Mossadeq coup ended the period of pluralism that had begun with the fall of Reza Shah in 1941, and inaugurated an extended period in which Mohammad Reza Shah ruled personally with few constitutional limitations. The oil dispute was resolved with an arrangement that gave

the Iranian government 50 per cent of the profits, out of a consortium in which the US companies had a 40 per cent stake, now equal to that held by the AIOC (renamed British Petroleum in 1954—BP). The increased oil revenue, which grew in turn as the industry developed, permitted a big expansion of government expenditure. Much of this, as in the time of Reza Shah, was spent on military equipment; augmented by $500 million of US military aid between 1953 and 1963 (many in government circles felt too much was being spent on the military budget and in 1959 that dispute contributed to the resignation of Abol-Hassan Ebtehaj, the head of the Planning and Budget Organisation

26

). In return the Shah aligned himself unequivocally with the West, and diplomatic relations with Britain were restored in 1954. But from 1953 onwards it was plain to all that the US was now the dominant external power in Iran.

After the coup the Shah’s government kept a tight grip on politics. Candidates for the elections to the eighteenth Majles in 1954 were selected by the regime and the assembly proved duly obedient. In 1955 the Shah dismissed Zahedi and effectively took control into his own hands. Mossadeq’s National Front was disbanded and Tudeh sympathisers were relentlessly pursued by a security agency (known as SAVAK from 1957) that grew increasingly efficient, with help from the CIA and the Israeli secret service, Mossad; and increasingly brutal. Two puppet political parties were set up for the Majles, controlled by the Shah’s supporters—

Melliyun

(National Party) and

Mardom

(People’s Party)—satirised as the ‘Yes’ party and the ‘Yes sir’ party.

27

Important members of the ulema like Kashani, and the prime marja-e taqlid, Ayatollah Borujerdi, had supported the coup of 1953 because they disliked what they saw as Mossadeq’s secularising tendency and the influence of Tudeh. They continued to support the Shah thereafter, and relations between the Shah and Borujerdi in particular, were cordial. But many clerics grew more uneasy and hostile as time went on.

The population of Iran had expanded from around 12 million at the beginning of the century to 15 million in 1938 and 19.3 million in 1950; it would jump to 27.3 million by 1968 and 33.7 million in 1976. The regime invested heavily in industry, but also in education, though the rural areas still

lagged behind. There was also substantial private investment, and over the years 1954-1969 the economy grew on average by seven or eight per cent a year.

28

As well as military expenditure, a lot of government money was spent on big, showy engineering projects, like dams—dams that sometimes never linked up to the irrigation networks that had been their justification. As in any other time of major change, the new often looked crass against the dignity of the old that was being pushed aside, and the benefits of change were distributed unequally. But there was a general improvement in material standards of living and the new, educated middle class expanded, encompassing entrepreneurs, engineers and managers as well as the older professions, the lawyers, doctors and teachers.

In 1957 a British diplomat with more than ordinary perspicacity wrote the following of Tehran, prefiguring the tensions that came into higher relief in the ’60s and ’70s and making an early differentiation between the different character of the westernised north of the city, and the more traditional, poorer south:

Here the mullahs preach every evening to packed audiences. Most of the sermons are revivalist stuff of a high emotional and low intellectual standard. But certain well known preachers attract the intelligentsia of the town with reasoned historical exposés of considerable merit… The Tehran that we saw on the tenth of Moharram [ie Ashura] is a different world, centuries and civilisations apart from the gawdy superficial botch of cadillacs, hotels, antique shops, villas, tourists and diplomats, where we run our daily round… but it is not only poverty, ignorance and dirt that distinguish the old south from the parvenu north. The slums have a compact self-conscious unity and communal sense that is totally lacking in the smart districts of chlorinated water, macadamed roads and (fitful) street lighting. The bourgeois does not know his neighbour: the slum-dweller is intensely conscious of his. And in the slums the spurious blessings of Pepsi Cola civilisation have not yet destroyed the old way of life, where every man’s comfort and security depend on the spontaneous, un-policed observation of a traditional code. Down in the southern part of the city manners and morals are better and stricter than in the villas of Tajrish: an injury to a neighbour, a pass at another man’s wife, a brutality to a child evoke spontaneous retribution without benefit of bar or bench.

29

In 1960 the Shah put forward a proposal for land reform, but by this time the economy was slowing down, and the US government (after January

1961 the Kennedy administration) was putting some pressure on the Shah to liberalise. Many of the senior ulema disliked the land reform measure (their extensive land holdings from endowments appeared to be threatened, and many considered the infringement of property rights to be un-Islamic), and Borujerdi declared a fatwa against it. The measure stalled. Prompted by the US, the Shah lifted the ban on the National Front, and their criticisms, along with the economic problems, led to strikes and demonstrations. At the beginning of 1963 the Shah regained the initiative with a package of reforms announced as the White Revolution. This included a renewed policy of land reform, privatisation of state factories, female suffrage, and a literacy corps of young educated people to address the problem of illiteracy in the countryside. Despite a boycott by the National Front (who insisted that such a measure should have been presented and applied by a constitutionally-elected Majles) the programme received huge support in a referendum, with 5.5 million out of 6.1 million eligible voters supporting it.

30

The programme went ahead, augmenting and broadening the changes in the country that were already afoot.

But early in 1963 a cleric little-known outside ulema circles, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, began to preach in Qom against the Shah’s government for its corruption, its neglect of the poor, and its failure to uphold Iran’s sovereignty in its relationship with the US (he also disliked the Shah’s sale of oil to Israel). He made this move at a time when, following the death of Ayatollah Borujerdi in 1961, many Iranian Shi‘a were unclear whom to follow as marja-e taqlid. In March, on the anniversary of the martyrdom of the Emam Ja’far Sadeq, troops and SAVAK agents attacked the

madreseh

where Khomeini was preaching and arrested him, killing several students at the same time. He was released after a short time but continued his attacks on the government. He made a particularly strong speech on 3 June, which was Ashura, and was arrested again early on 5 June.

31

When the arrest became known there were demonstrations in Tehran and several other major cities, which drew force from the intense atmosphere of mourning for Emam Hosein, and were repeated and spread more widely in the days that followed. The Shah imposed martial law and put troops on the streets but hundreds of demonstrators (at least)

were killed before the protests ended. These deaths, especially because they took place at Ashura, invited comparison with the martyrs of Karbala on the one hand, and the tyrant Yazid on the other.

Khomeini was released in August, but despite SAVAK announcements that he had agreed to keep quiet he continued to speak out, and was rearrested. Finally, he was deported and exiled in 1964 after a harsh speech attacking both the Iranian and US governments for a new law that gave the equivalent of diplomatic immunity to US military personnel in Iran:

They have reduced the Iranian people to a level lower than that of an American dog. If someone runs over a dog belonging to an American, he will be prosecuted. Even if the Shah himself were to run over a dog belonging to an American, he would be prosecuted. But if an American cook runs over the Shah, the head of state, no one will have the right to interfere with him…

32

Shortly after the new law was passed in the Majles a new US loan of $200 million for military equipment was agreed—a conjunction all too reminiscent of the kinds of deals done with foreigners in the reign of Naser od-Din Shah. Initially Khomeini went to Turkey in exile, then to Iraq and eventually (after the Shah put pressure on the Iraqi government to remove him from the Shi‘a centre in Najaf) to Paris in 1978. In Iran, protest died down, aside from occasional manifestations at Tehran University and from members of the ulema. For the Shah, the message from the episode appeared to be that he could govern autocratically and overcome short-term dissent with repression. In the longer term, he believed, his policies for development would bring benefits to ordinary people and secure his rule.

Khomeini

Ruhollah Khomeini was born in September 1902 in Khomein, a small town between Isfahan and Tehran. He came from a family of

seyyed

(descendants of the Prophet) whose patriarchs had been mullahs for many generations and may originally have come from Nishapur. In the eighteenth century one of his ancestors had moved to India, where the family had lived in Kintur near Lucknow, before his grandfather (known

as Seyyed Ahmad Musavi Hindi) moved back to Persia and settled in Khomein in about 1839. He bought a large house there and was a man of property and status. Ahmad’s son Mostafa studied in Isfahan, Najaf and Samarra and married the daughter of a distinguished clerical family. He belonged to the upper echelons of the ulema, a cut above the mullahs who had to make a living as jobbing teachers, legal notaries or preachers. This made him an important figure in the area, and it seems that it was while he was attempting to mediate in a local dispute that he was murdered in 1903, when Ruhollah, his third son, was only six months old.

33

Ruhollah grew up in Khomein through the turbulent years of the Constitutional Revolution and the First World War, over which period Khomein was raided a number of times by Lori tribesmen. In 1918 his mother died in a cholera epidemic, leaving him an orphan as he was about to go into the seminary nearby in Soltanabad. It may be that the absence of his father as a child and becoming orphaned as a youth added impetus to the young Khomeini’s ambition and drive to excel in his studies. Later he moved to Qom, wearing the black turban of a seyyed, as a student of Shaykh Abdolkarim Ha’eri. There he received the conventional education in logic and religious law of a mullah,

34

becoming a mojtahed in about 1936, which was a young age and a sign of his promise. From that time he began to teach and write. He was always a little unconventional, having an interest in poetry and mysticism (erfan) that more conservative mullahs would have disapproved of. He read Molla Sadra’s

Four Journeys

and the

Fusus al-Hikam

of Ibn Arabi, and his first writings were commentaries on mystical and philosophical

texts. In the ’30s he studied philosophy and erfan with Mirza Mohammad Ali Shahabadi, who as well as being an authority on mysticism, believed in the importance of explaining religious ideas to ordinary people in language they could understand. Shahabadi was opposed to the rule of Reza Shah and also influenced Khomeini’s politics.

35

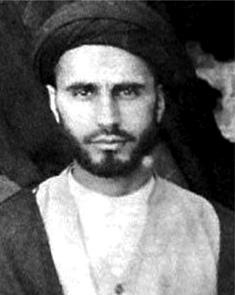

Fig. 19. Ruhollah Khomeini as a student—an extraordinary mojtahed.

Khomeini had a strong sense of himself (and of the dignity of the ulema as a class) and always dressed neatly and cleanly—not affecting an indifference to clothes or appearance as some young mullahs did. He struck many people as aloof and reserved, and some as arrogant, but his small circle of students and friends knew him to be generous and lively in private. For his public persona as a teacher and mullah it was necessary for him to exemplify authority and quiet dignity. Through the ‘40s and ’50s, continuing to teach in Qom, it is perhaps correct to think of Khomeini taking a position between the activism of Ayatollah Kashani on the one hand, anti-colonial and anti-British (he was interned by the British between 1942 and 1945); and that of Ayatollah Hosein Borujerdi on the other, more conservative, more withdrawn, tending to quietism and intervening only seldom in political matters.

36

But Khomeini’s combination of intellectual strength, curiosity and unconventionality made him different from either; potentially more creative and innovative, though for the time being still deferring to his superiors in the hierarchy of the ulema. Khomeini was made an Ayatollah after the death of Borujerdi in March 1961, by which time he was already attracting large and increasing numbers of students to his lectures on ethics, and was regarded by some as their marja, their object of emulation.