Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia (5 page)

Read Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia Online

Authors: David Vine

Tags: #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #Political Science, #Human Rights, #History, #General

Too often, however, the debates on empire have ignored and turned away from the lives of those impacted by empire. Too often analysts turn to abstract discussions of so-called foreign policy realism or macro-level

economic forces. Too often, analysts detach themselves from the effects of empire and the lives shaped and all too often damaged by the United States. Proponents of U.S. imperialism in particular willfully ignore the death and destruction caused by previous empires and the U.S. Empire

**

alike.

45

In 1975, the

Washington Post

exposed the story of the Chagossians’ expulsion for the first time in the Western press, describing the people as living in “abject poverty” as a result of what the

Post

’s editorial page called an “act of mass kidnapping.”

46

When a single day of congressional hearings followed, the U.S. Government denied all responsibility for the islanders.

47

From that moment onward, the people of the United States have almost completely turned their backs on the Chagossians and forgotten them entirely.

Unearthing the full story of the Chagossians forces us to look deeply at what the United States has done, and at the lives of people shaped and destroyed by U.S. Empire. The Chagossians’ story forces us to focus on the damage that U.S. power has inflicted around the world, providing new insight into the nature of the United States as an empire. The Chagossians’ story forces us to face those people whom we as citizens of the United States often find it all too easy to ignore, too easy to close out of our consciousness. The Chagossians’ story forces us to consider carefully how this country has treated other peoples from Iraq to Vietnam and in far too many other places around the globe.

48

At the same time, we would be mistaken to treat the U.S. Empire simply as an abstract leviathan. Empires are run by real people. People made the decision to exile the Chagossians, to build a base on Diego Garcia. While empires are complex entities involving the consent and cooperation of millions and social forces larger than any single individual, we would be mistaken to ignore how a few powerful people come to make decisions that have such powerful effects on the lives of so many others thousands of miles away. For this reason, the story that follows is two-pronged and bifocaled: We will explore both sides of Diego Garcia, both sides of U.S. Empire, focusing equally on the lives of Chagossians like Rita Bancoult and the actions of U.S. Government officials like Stu Barber. In the end

we will reflect on how the dynamics of empire have come to bind together Bancoult and Barber, Chagossians and U.S. officials, and how every one of us is ultimately bound up with both.

***

49

To begin to understand and comprehend what the Chagossians have suffered as a result of their exile, we will need to start by looking at how the islanders’ ancestors came to live and build a complex society in Chagos. We will then explore the secret history of how U.S. and U.K. officials planned, financed, and orchestrated the expulsion and the creation of the base, hiding their work from Congress and Parliament, members of the media and the world. Next we will look at what the Chagossians’ lives have become in exile. While as outsiders it is impossible to fully comprehend what they have experienced, we must struggle to confront the pain they have faced. At the same time, we will see how their story is not one of suffering alone. From their daily struggles for survival to protests and hunger strikes in the streets of Mauritius to lawsuits that have taken them to some of the highest courts in Britain and the United States, we will see how the islanders have continually resisted their expulsion and the power of two empires. Finally, we will consider what we must do for the Chagossians and what we must do about the empire the United States has become.

The story of Diego Garcia has been kept secret for far too long. It must now be exposed.

*

Rita’s last name has since changed to Isou, but for reasons of clarity I will refer to her throughout by the name Bancoult.

**

Throughout the book I use the term

U.S. Empire

rather than the more widely recognized

American Empire

. Although “U.S. Empire” may appear and sound awkward at first, it is linguistically more accurate than “American Empire” and represents an effort to reverse the erasure of the rest of the Americas entailed in U.S. citizens’ frequent substitution of

America

for the

United States of America

(America consists of all of North and South America). The name of my current employer, American University, is just one example of this pattern: Located in the nation’s capital, the school has long touted itself as a “national university” when its name should suggest a hemispheric university. The switch to the less familiar U.S. Empire also represents a linguistic attempt to make visible the fact that the United States is an empire, shaking people into awareness of its existence and its consequences.

***

Those interested in reading more about the book’s approach as a bifocaled “ethnography of empire” should continue to the following endnote.

THE ILOIS, THE ISLANDERS

“

Laba

” is all Rita had to say. Meaning, “out there.” Chagossians in exile know immediately that

out there

means one thing: Chagos.

“

Laba

there are birds, there are turtles, and plenty of food,” she said. “There’s a leafy green vegetable . . . called cow’s tongue. It’s tasty to eat, really good. You can put it in a curry, you can make it into a pickled chutney.

“When I was still young, I was a little like a boy. In those times, we went looking” for ingredients for “curries on Saturday. So very early in the morning we went” to another island and came back with our food.

“By canoe?” I asked.

“By sailboat,” Rita replied.

Peros Banhos “has thirty-two islands,” she explained. “There’s English Island, Monpatre Island, Chicken Island, Grand Bay, Little Bay, Diamond, Peter Island, Passage Island, Long Island, Mango Tree Island, Big Mango Tree Island. . . . There’s Sea Cow Island,” and many more. “I’ve visited them all. . . .”

1

EMPIRES COMING AND GOING

“A great number of vessels might anchor there in safety,” were the words of the first naval survey of Diego Garcia’s lagoon. The appraisal came not from U.S. officials, but from the 1769 visit to the island by a French lieutenant named La Fontaine. Throughout the eighteenth century, England and France vied for control of the islands of the western Indian Ocean as strategic military bases to control shipping routes to India, where their respective East India companies were battling for supremacy over the spice trade.

2

Having occupied Réunion Island (Île Bourbon) in 1642, the French replaced a failed Dutch settlement on Mauritius (renamed Île de France) in 1721. Later they settled Rodrigues and, by 1742, the Seychelles. As with its Caribbean colonies, France quickly shifted its focus from military to commercial interests.

3

French settlers built societies on the islands around enslaved labor and, particularly in Mauritius, the cultivation of sugar cane. At first, the French Company of the Indies tried to import enslaved people from the same West African sources supplying the Caribbean colonies. Later the company developed a new slaving trade to import labor from Madagascar and the area of Africa known then as Mozambique (a larger stretch of the southeast African coast than the current nation). Indian Ocean historian Larry Bowman writes that French settlement in Mauritius produced “a sharply differentiated society with extremes of wealth and poverty and an elite deeply committed to and dependent upon slavery.”

4

Chagos, including Peros Banhos and Diego Garcia, remained uninhabited throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, serving only as a safe haven and provisioning stop for ships growing familiar with what were sometimes hazardous waters—in 1786, a hydrographer was the victim of a shipwreck. But as Anglo-French competition increased in Europe and spilled over into a fight for naval and thus economic control of the Indian Ocean, Chagos’s central location made it an irresistible military and economic target.

5

France first claimed Peros Banhos in 1744. A year later, the English surveyed Diego Garcia. Numerous French and English voyages followed to inspect other island groups in the archipelago, including Three Brothers, Egmont Atoll, and the Salomon Islands, before Lieutenant La Fontaine delivered his prophetic report.

6

TWENTY-TWO

Like tens of millions of other Africans transported around the globe between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries, Rita’s ancestors and the ancestors of other Chagossians were brought against their will. Most were from Madagascar and Mozambique and were brought to Chagos in slavery to work on coconut plantations established by Franco-Mauritians.

The first permanent inhabitants of the Chagos Archipelago were likely 22 enslaved Africans. Although we do not know their names, some of today’s Chagossians are likely their direct descendants. The 22 arrived around 1783, brought to the island by Pierre Marie Le Normand, an influential plantation owner born in Rennes but who left France for Mauritius at the age of 20.

7

Only half a century after the settlement of Mauritius, Le Normand petitioned its colonial government for a concession to settle Diego Garcia. On February 17, 1783, he received a “favourable reply” and “immediately prepared his voyage.”

8

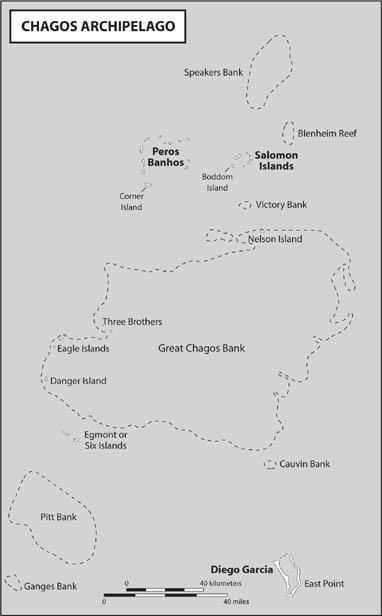

Figure 1.1 The Chagos Archipelago, with Peros Banhos and Salomon Islands at top center, Diego Garcia at bottom right.

Three years later, apparently unaware of Le Normand’s arrival, the British East India Company sent a “secret committee” from Bombay to create a provisioning plantation on the atoll. Although they were surprised to find the French settlement, the British party didn’t back down. On May 4, 1786, they took “full and ample Possession” of Diego Garcia and Chagos “in the name of our Most Gracious Sovereign George the third of Great Britain, France and Ireland King Defender of the faith

etc.

And of the said Honourable Company for their use and behoof.”

9

Unable to resist the newcomers, Le Normand left for Mauritius to report the British arrival. When France’s Vicompte de Souillac learned of the landing, he sent a letter of protest to Bombay and the warship

Minerve

to reclaim the archipelago. To prevent an international incident liable to provoke war, the British Council in Bombay sent departure instructions to its landing party. When the

Minerve

arrived on Diego, its French crew found the British settlement abandoned and its grain and vegetable seeds washed into the sand.

10

While France won this battle, governing Chagos along with the Seychelles as dependencies of Mauritius, its rule proved short-lived. By the turn of the nineteenth century and the Napoleonic Wars, French power in the Indian Ocean had crumbled. The British seized control of the Seychelles in 1794 and Mauritius in 1810. In the 1814 Treaty of Paris, France formally ceded Mauritius, including Chagos and Mauritius’s other dependencies (as well as most of France’s other island possessions worldwide), to Great Britain. Succeeding the Portuguese, Dutch, and French empires before it, the British would rule the Indian Ocean as a “British lake”

11

for a century and a half, until the emergence of a new global empire.

“IDEALLY SUITED”

Ernestine Marie Joseph Jacques (Diego Garcia). Joseph and Pauline Pona (Peros Banhos). Michel Levillain (Mozambique). Prudence Levillain (Madagascar). Lindor Courtois (India). Theophile Le Leger (Mauritius). Anastasie Legère (Three Brothers).

12

These are the slave names and birthplaces of some of the Chagossians’ first ancestors.

13

While most arrived

from Mauritius, some may have come via the Seychelles and on slaving ships from Madagascar and continental Africa as part of an illegal slave trade taking advantage of Chagos’s isolation from colonial authority.

14

Not long after Le Normand established his settlement, hundreds more enslaved laborers began arriving to build a fishing settlement and four more coconut plantations established by Franco-Mauritians Dauquet, Lapotaire, Didier, and the brothers Cayeux. By 1808 there were 100 enslaved people working under Lapotaire alone. By 1813, a similar number were working in Peros Banhos, as settlement spread throughout an archipelago judged to have “a climate ideally suited to the cultivation of coconuts.”

15

Less than eight degrees from the equator, Chagos’s environment is marked by “the absence of a distinct flowering season and the gigantic size of many native and cultivated trees.” The islands are also free from the cyclones (hurricanes) that frequently devastate Mauritius and neighboring islands. Meaning that coconut palms produce bountiful quantities of nuts year round for potential harvest. Hundreds more enslaved Africans were soon establishing new plantations at Three Brothers, Eagle and Salomon Islands and at Six Islands.

16