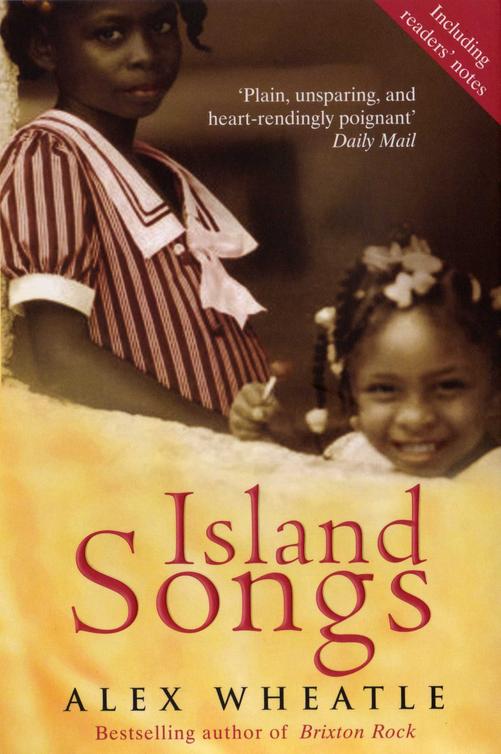

Island Songs

Authors: Alex Wheatle

ALEX WHEATLE

- Title Page

- Prologue

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Readers’ Notes

- About the Author

- Copyright

South London

July 2003

Two bridesmaids sporting matching pink dresses, white socks and pink ribbons in their hair, danced the last waltz. They were at their uncle Royston’s wedding reception. Giggling and holding hands, they had the floor to themselves. They enjoyed the polite applause that rippled around the decorated hall from the remaining guests as they mimicked poses and dance steps that they had seen enacted by their elders earlier in the evening.

Watching the girls from the top banquet table was their grandmother and great aunt, pride glowing. They were both in floral dresses, white shoes and white hats and their expressions told of rich experiences and lost dreams. The scene before them reminded them of their own childhood and they could almost hear the gentle Jamaican breezes curling and weaving through the leaves of the Blue Mahoes in the Claremont valley.

“Dey look so beautiful out der,” gushed the grandmother, Hortense, clapping enthusiastically. She was thinking of her own wedding day many years ago. It was in rural Jamaica and she wondered what her mother would have thought of the plush surroundings. Today, she spotted an old man nursing a paper cup full of rum punch sitting alone in a corner. He was staring vacantly at the remains of the wedding cake. Irritated skin framed his eyes. He looked like a rejected male lion.

“Jenny,” Hortense called. “Yuh nah gwarn to say hello to Jacob? Yuh two ’ave been avoiding each udder all evenin’.”

Jenny’s brow hardened. She shot Jacob a dismissive glance. “We ’ave not’ing to say to each udder.”

“But yuh were married to each udder fe over twenty years,” stated Hortense. “Yuh cyan’t be civil to each udder?”

Jenny inhaled deeply, attempting to master some dark emotion. Her eyes flicked between her sister and Jacob and a sense of guilt weighed heavily on her mind. Why did he have to turn up, she thought to herself. Maybe

he

wanted to say his last piece before she and Hortense flew back to Jamaica for good in a week’s time. Well, she for one would not entertain him.

“Hortense,” Jenny said softly, leaning over to speak in her sister’s ear. “People divorce an’ live dem separate lives. We don’t need to talk to each udder every time we pass. Me don’t know why yuh invite him.”

Draining the last of her champagne, Hortense stood up. “Well, me gwarn to say hello to him. Me don’t see him fe fifteen years now. We was all so close one time.”

“

Hortense

!” Jenny protested, panic coursing through her veins.

Ignoring her sister, Hortense walked across the varnished wooden floor to where Jacob was sitting. Jacob seemed not to acknowledge her presence. He gazed at the crumbs and lumps of icing as if they offered some kind of meaning to his life.

“Jacob,” Hortense greeted, trying to raise a smile while sensing her sister’s eyes boring into her back. She offered Jacob her hand but he refused it. She studied his face and noticed the curved lines of bitterness marking his forehead. The tufts of hair around his ears and clinging on the back of his head were coloured stress-white. “It’s been ah long time,” Hortense resumed. “Me glad dat yuh did accept me invitation to me son wedding. Yuh two were close. We was all so…”

Sipping from his cup again, Jacob looked over Hortense’s left shoulder. He spotted his ex-wife’s anxious looks and summoned up a cruel smile.

“I’m not here fe ya benefit, Hortense. I come to give ya son,

my

nephew, my blessing.”

“Jacob, me cyan’t understand why ya like dis to me. Wha’ did me ever done to yuh?”

Jacob grinned again, his cheeks unmoving. He enjoyed

Hortense’s discomfort but his eyes still betrayed a sour memory. “Yuh know, Hortense, my fader did ah warn me about ya family. Him used to tell me stories about ya devil papa. I never believed him at de time. An’ he did never waan me to marry Jenny. Him tell me de whole lot ah yuh was cursed by de devil himself. But like ah fool I married into ya godforsaken family. An’ me will regret it ’til de end ah my days. My fader died cursing ya papa’s very name.”

Placing her hands upon her hips, Hortense leaned in closer to Jacob and glared at him. “Yuh lucky dis is me son wedding an’ me don’t waan to cause nuh fuss. It’s not me fault why yuh an’ Jenny divorce an’ its about time yuh get over it! It’s been fifteen years now. Me could never understan’ it anyway becah der was nuhbody else involve.”

Jacob locked Hortense in an intense stare. He paused before breaking out into a manic chuckle. “Wasn’t der?” he asked, almost mockingly.

Hortense could hear the clip-clip of Jenny’s heels approaching. She returned Jacob’s gaze with interest. The music was fading away and Hortense, conscious of people around her, lowered her voice. “Yuh implying dat me sister did ’ave relations wid ah nex’ mon?”

Reaching Hortense’s side, Jenny immediately tried to usher her away. “Come, Hortense,” she whispered, looking about her. “Don’t waste ya time wid dat fool. He’s all bitter an’ twisted.”

Downing his drink, Jacob stood up unsteadily. He turned to Hortense. “An’ she call me bitter an’ twisted! Hortense, I cyan’t tell yuh de trut’ becah it would kill yuh an’ I truly love yuh as ah friend. As de Most High is my witness! My marriage was ah sham. Ah fraud! Yuh better believe it. Becah Jenny only did ah love two mon in dis world. One was her pagan fader an’ de udder was

not

me.”

Feeling her heartbeat accelerate and sensing that the other wedding guests were taking an interest, Jenny pulled Hortense’s left arm and walked her away. Jacob, not finished and slurring his words, yelled, “Hortense, why yuh don’t ask ya so-called sweet sister who she really did ah love!”

Jenny closed her eyes in mortification, gratefully dropping into a

nearby chair. With a handkerchief she wiped away the sweat that had collected upon her temples. She finally turned to her sister who took a seat beside her. She took Hortense’s left hand and held it tightly within her own trembling hands. “Don’t lissen to him, Hortense. Jacob ah talk pure fart. Me cyan’t wait ’til we get ’pon dat plane to carry us home fe good.”

Shocked by what Jacob had said, Hortense replied, “ah change has come over him. Me don’t know why. Him even call Papa ah devil. Wha’ is ah matter wid dat mon? Wha’ do him mean dat de trut’ coulda kill me?”

Feeling a weight pressing upon her conscience, Jenny thought of the other man. Then she thought of her father, as she always did in time of crisis. She could see him in the picture of her mind, tall and proud. He was strapping on his size thirteen boots, slinging his crocus bag full of tools over his broad shoulders and setting off to work, his long strides eating up the ground.

Claremont, Jamaica

October 1945

Joseph Rodney rubbed his hands to free the clingy particles of soil, lifted his head and surveyed the distant hills that were shrouded in mist. He could see the faint light-brown traces of footpaths and goat byways that snaked upwards and faded into the horizon. The dense vegetation was a rich green, peppered with the vibrant colours of fruits and plants. A stream sliced its way through a lush valley of tall Blue Mahoe trees. The Claremont valley offered only meagre patches where the folding, rolling lands met on a rise.

Joseph could see Mr Welton DaCosta’s livestock grazing upon the sloping field above the village. Although he was grateful to his father-in-law, Neville, who presented him with the strip of good soil he now laboured on, Joseph hoped of owning and breeding livestock one day, the dream of all Jamaican country folk.

The cooling breeze that drifted in from the Caribbean sea was still and Joseph guessed that the seasonal wind and rains would surely come soon; he sensed it in the balmy aroma of the soil. He looked up again and wondered if the terrain he was studying locked away as many secrets as he did, nightmarish memories that he had yet to even tell his wife. He turned slowly to view the ramshackle dwellings of villagers who had constructed their homes precariously on steep hillsides and astride grassy escarpments, the patchwork of corrugated zinc roofs reflecting the light. A hot Jamaican sun was setting, but on this secluded part of the north of the island, two thousand feet above sea level, the yellow eye didn’t rage as it did on the flat southern plains, where most of the sugar plantations were located and where the crocodiles swam silently in

swampy rivers thick with reeds.

Joseph thought of a white man he had once seen and how he seemed so uncomfortable sweltering under the sun, forever dabbing his reddened, peeling face as he rode by. Joseph was unaware that the man was employed by the British colonial government to ‘oversee’ the Crown Lands (of which the Claremont valley was a part) and report any undue incidents; it was whispered in these parts that the man had fathered three children in Browns Town and there, locals stole questioning glances at caramel-skinned children.

“Madness!” Joseph laughed. “Dat white mon face did ah look like spoil red pepper!”

Taking off his wide-brimmed, straw hat, Joseph swabbed the sweat off his brow with a huge mud-stained hand, replaced it so that it covered his eyebrows and muttered to himself, “dem neva learn. When Massa God decide to blow him cruel wind as he surely will, den de people der ah mountain side will be tossed to de sky like ah John-Crow feader.”

Joseph had finished his work for the day and he was satisfied that the callaloo, lettuce, yams, tomato and hot peppers would be ripe for picking before the next full moon. He knew that the pumpkins and sweet potato were not quite ready. Joseph felt he could probably get away with it if he decided to include the pumpkins and sweet potato in his harvest offerings to the church, but that would be cheating. He also didn’t want the preacher man, Mr Forbes, to offer his fellow villagers any gossip or ‘susu’ talk of how the Rodney family did not give of their best.

“Him t’ink him so special wid him big house an’ him big talk,” Joseph thought. “Me’d rader cross crocodile river inna flimsy broad leaf dan gwarn to dat mon church every Sunday. Him lucky him getting any harvest from me becah me only do it fe Amy. Me don’t waan nuhbody to look wid bad eye to her or me family.”

Joseph recalled the preacher’s reluctance to perform the wedding ceremony for him and Amy twenty years ago. The wedding feast

had consisted only of ardough bread, chicken, rice and peas, and Amy was dressed in her mother’s simple white frock, the same garment in which she had been baptised. Many villagers boycotted the festivities. “Why is sweet pretty Miss Amy marrying dat black, devil mon?” they asked out aloud. “She is ah nice Christian girl. An’ dis devil mon mus’ ah put spell ’pon Misser Neville to get dat land!”

It was a Sunday and sometimes Joseph hated the solitude that he felt working on the Sabbath. Despite having his own family he felt a loneliness that would never leave him alone. Everybody else was taking their rest or singing their praises to the Most High in Mr Forbes’s church – the biggest building in the village that also doubled as the school. Joseph’s youngest daughter, Hortense, loved the singing there and her sister, Jenny, excelled in her lessons. Jenny looks so much like my own mother, Joseph thought. Bless her tears.

A strong pang of guilt wracked Joseph. He hadn’t seen his mother for thirty years, having left home amid total devastation at fifteen years of age. He always pictured her in his mind weeping. Always weeping. “Ah, pure madness!” Joseph muttered to himself, shaking his head. He didn’t even know if she was still alive or indeed if any of his siblings were. A disturbing image of his older brother, Naptali, chilled his bones; the broken expression, the complete loss of a long-held dream and those crazy eyes! He had only seen him once, for just one day of his life, in the fall of 1914. A day that he could recall in minute detail from the time he blinked sleep from his eyes to the sound of the debating crickets of

that

night when Joseph tried but failed to sleep.

A call interrupted Joseph’s recollections. “Moonshine! Moonshine!” Looking down the hill where the voice was coming from, Joseph knew it could only be one person. Kwarhterleg. For nobody else in the village dared to call Joseph by this nickname, although they felt free to do so when Joseph was out of earshot. The inhabitants of this tiny hamlet were immediately struck by Joseph’s blackness and his intimidating physique. Fearful of him, they thought

he was some kind of disciple of the devil, they referred to Joseph as him black ’til him shine an’ Old Screwface mus’ ah sen’ fe him to turn we away from praising de Most High’. As years passed by this description was shortened to the moniker ‘Moonshine’.

Joseph knew he was descended from the Maroons, a fierce tribal people who would not yield to slavery and fought their oppressors with everything they had. Many of them had won their freedom from their Spanish captors upon arrival on Jamaican soil at a place that is now called Runaway Bay. From there the Maroons made their way to ‘Cockpit Country’, the mountainous interior of the island. The Spanish conquistadors, fearful that the legendary Coromanty curse might well strike them down if they dared to pursue the runaway slaves, let them be. The British, after assuming control of Jamaica, decided to send in waves of red-coats to hunt the Maroons down, ignoring the local warnings of house slaves who spoke of the mighty deeds of the Maroon warrior queen, Nanny. Hardly any of these forces would look on their homeland again and the ones that did never did so with sane eyes. The British imperialists even resorted to shipping over fierce Indians from the Mosquito Coast in Central America, promising them lavish rewards for quelling the Maroons’ spirit of resistance. They fared no better, never to be seen or heard of again.

Born in Accompong Town, the first Maroon settlement in Jamaica, not more than a fifteen minute John-Crow journey from the bony wastelands of Cockpit Country, Joseph was unfortunate that when he arrived in Claremont, in the northern parish of St Anne, that very few people there had ever seen Maroons or knew about them, save a handful of old wizened folk who spent their time teaching their grandchildren the art of tilling and telling fireside tales of ghosts and demons. They offered Joseph vague and knowing nods whenever he walked by, never revealing what lay behind their polite greetings.

A few of the Claremont elders knew that the land they had tilled and lived on for two hundred years or so was gained after a colonial government agreement with African ex-slaves, who were once

owned by the Spanish and later roamed free following the Spanish withdrawal from the island. It was decided that these former slaves would be granted land if they hunted and captured newly-escaped slaves from the profitable plantations. Even a number of Maroons complied with this contract. Feeling a deep sense of guilt, aged Claremontonians carried the secret of their inheritance to the grave.

“Don’t ask nuh question an’ me cyan’t tell yuh nuh lie,” they would say.

The people of the Claremont valley kept to themselves, worked their land and praised the God of the King James Bible. Most believed that any malady or handicap that visited a man was God’s punishment of his sins. Many Jamaican rural folk were even unaware that a year ago, in 1944, their colonial masters had granted voting rights to every male or female over the age of twenty-one. Those who were not ignorant of this shrugged their shoulders and said, “it’ll will nah effect me if me crops nuh ripe an’ sweet. Wha’ good is ah blasted vote!” The people who lived here preferred the devil they knew.

Kwarhterleg employed a crutch hewn from a branch of a tree, its shoulder shaped by his left armpit due to constant use since he was seventeen. The left leg of his stained, torn khaki pants was tied up in a knot just below the knee. He hobbled up the goat’s path to Joseph’s small plot of land, holding a soiled plastic bag full of something that had a potent aroma. In his late sixties, Kwarhterleg didn’t have much hair, but made up for it with his untamed grey beard. He was a foot shorter than Joseph, and leaner, and his hooded eyes spoke of some distant betrayal.

Stumping his way to Joseph’s patch of land, Kwarhterleg threw away his crutch and sat down. While he caught his breath, he seemed apprehensive, fearful of the news he had to deliver.

“Yuh bring me de yard of tobacco me sen’ yuh to get?” Joseph asked casually, taking out a homemade pipe from his pocket. He had named his smoking pipe Panama. “Misser Patterson satisfied wid de pear, plum and strong-back leaf me give him?”

“Yes, mon. Him well pleased wid de strong-back leaf. Him son

ketch ah fever an’ has ah serious need fe it,” replied Kwarhterleg, his tone full of reverence. “It’s inna de bag.”

“Well, bring it come den,” demanded Joseph impatiently.

Kwarhterleg emptied the contents of the bag on the ground. Joseph, in his trouser pockets, found a pair of rusty scissors and proceeded to snip the tobacco leaves into a fine cut before generously stuffing his pipe; if he had had more patience he would have sweetened it with sugar water and left it out to dry. As Joseph lit himself what he thought was a well-earned smoke, Kwarhterleg watched his long-time friend with concern.

“Moonshine,” he began with caution, “somet’ing serious happen ah church today. Me affe tell yuh. Serious t’ing. Long time yuh tell me to inform yuh if de Preacher Mon trouble any of ya family.”

Exhaling his smoke, Joseph turned to look at his friend and scolded, “Kwarhterleg! Yuh love mek big bull outta young goat! Tell me wha’ happen, mon! Me don’t ’ave nuh time fe long journey around broad bush.”

“Jenny get ah serious beating today, mon,” Kwarhterleg revealed. He went on to tell Joseph of what happened today at church. Jenny was playing tag with her sister during the singing of a hymn and had squealed when Hortense had pinched her. The preacher slammed his hymn book closed, looked upon his congregation in disbelief that a child had interrupted the singing and walked slowly over to Jenny. His eyes fixed upon the girl’s petrified expression, he struck her twice with an open palm, the sound echoing in the church hall. Jenny fell off her chair and banged her head upon the dusty wooden floor but she was determined not to cry. Still glaring at the child and looming over her, the preacher recognised Joseph’s defiance. He offered Jenny a dismissive glance before returning to the pulpit. Amy, Jenny’s mother, helped her daughter to her feet as fury rose within her. Amy was about to protest when she spotted her father, Neville, who was gesturing with his hands to calm down. She could read his lips. “Nuh cause bangarang inna God’s house.”

Not betraying an emotion, Joseph toked twice on his pipe and peered into the mists. He said nothing for ten minutes, until he had finished smoking. Kwarhterleg was filling his own wonky wooden

pipe when finally Joseph spoke. “Amy say anyt’ing?” he asked innocently.

“Nuh, mon. Yuh know so she won’t say anyt’ing to de Preacher-Mon. Who would? Ah mon of God dat. Serious t’ing! If yuh cuss de Preacher-Mon den Old Screwface will set his mark ’pon yuh an’ yuh will surely ketch ah fire.”

“Me nah ’fraid of nuh Preacher-Mon or de devil himself or Old Screwface as yuh like to call him,” said Joseph defiantly. He stood up and examined his cutlass that was resting six feet away from him on the ground; the cutting edge of the blade stained brown from the soil. “Come Kwarhterleg! Amy should ’ave dinner ready an’ me sure ya belly ah tickle yuh like hog sniffing him tripe dat he cyan’t see. An’ me affe talk to Preacher-Mon.”

Collecting his tools, pick, spade and cutlass, Joseph placed them inside an old crocus bag, slung it over his shoulder and started off. Kwarhterleg hobbled behind him, trying to keep up with Joseph’s long strides, his unlaced black boots making clear imprints in the rich soil. Refusing to walk more than thirty paces in a straight line, Joseph would suddenly zigzag to confuse any malevolent spirits that he thought could be pursuing him; even Old Screwface himself might take matters in hand after his recent comments, Joseph thought.

They went downhill, following the goat’s path through a forest of palm trees before passing groves of bamboo, tambarine and ackee. It became hotter as they declined further, the mosquitoes becoming more numerous, energetically skitting through the dust. They soon saw the first corrugated zinc roofs of the sparse dwellings of their village.

Most of the homes had only two tiny rooms – one for sleeping and the other for storing farming tools, cooking utensils, brushwood and water urns. A kerosene lamp, hooked on a wooden beam near the front door, provided light. Everybody had an outside kitchen – a corrugated aluminium roof set upon wooden stilts and a low fireplace. Some villagers kept their fires going all day to ward off the mosquitoes. Between the home and the kitchen was a patch of rock-hard ground where the chickens scratched, bare-footed

children played, goats strayed and skinny yapping dogs – if they were bold enough to risk a thrashing – snouted for scraps. The village itself was sheltered by green-cloaked hills on all sides.