Jack the Ripper (8 page)

Authors: The Whitechapel Society

The mere circumstance and timing of his death has, undoubtedly, made Montague John Druitt one of the most persistent of all suspects since he was fully revealed to the wider world in the 1950s. This has been given extra buoyancy by the forceful fact that a high-ranking police official, although one who did not take part in the Whitechapel murder investigation in 1888, named Druitt as a subject in a clandestine report.

Nevertheless, Druitt’s suicide, although exquisitely timed for the assumed ending of the murder series in late 1888, is still the only real circumstantial evidence we have against Druitt. The thoroughly impenetrable ‘private information’ from Druitt’s family, which might yield more detailed investigation and debate, is mere speculation. Of course, added to these complexities, we must always acknowledge the

sine qua non

that all Jack the Ripper suspects must display a seriously valid account for the abrupt ending of the murder series. Druitt fits into this very well.

It is only fair then, to look deeper into the real element of the pertinacity of suspicion against Druitt – his suicide. Aside from the difficulty in establishing a proper and detailed examination of the familial insights, we must assume that the major suspicion against Druitt is predicated on his suicide. Taking out of the equation the sophistry of murder upon Druitt, it is his suicide that we must account for.

If Druitt was Jack the Ripper, his suicide is easily explained. As Macnaghten said, by associational intimation, Druitt’s mind seemed to have given way ‘after his awful glut in Miller’s Court…’ Therefore, remorse took hold of him and he took the only way out, as he saw it. Some serial killers may attempt suicide, but there are many more that do not.

A more viable explanation for Druitt’s suicide may be more obvious; namely, the circumstances surrounding his dismissal from Mr Valentine’s school. One might assume – and assumption it is – that if Druitt had been involved in an illegal act of a sexual nature, he may have lost the rigid

esprit de corps

amongst his peers. Druitt did, however, seemingly avoid arrest for this ‘serious trouble’ and was only dismissed. Of course, we can only assume that this was the reason for his dismissal – there is no shred of evidence to confirm it. Other viable reasons could equally be a conflict with Mr Valentine, or theft, or dereliction of duty. This still brings us back to the subject of Druitt’s suicide, and ultimately how it fits into any significant suspicion against him.

Depression can be a major cause of suicide, especially amongst young men. Druitt seems more likely to have been going through some personal turmoil; as such a suicide would indicate. It is a reasonable scenario that dismissal from the school could have been related to depression; it could have been affecting Druitt’s mental equilibrium and conduct at the school, or the cordiality of his relations with his employer, Mr Valentine. Being in the employ of such an establishment as Mr Valentine’s, despite its low pay and Druitt’s other activities, shows a man who had actively tried to engage himself within a rigid social circle of people. Such a fracturing of these relations, as a result of depression or such related problems, could have caused ostracisation for Druitt; as the Victorian elite looked to avoid association with the ‘mentally’ ill. This, in turn, could only have compounded Druitt’s problems.

There is additional evidence that Druitt was suffering from serious depression; amongst his possessions in his room was a suicide note, in the form of a letter addressed to his elder brother, William. In this letter he indicated the reason for his decision to take his own life: ‘Since Friday I felt that I was going to be like mother, and it would be best for all concerned if I were to die.’ Far from explicating reasons for being a serial killer, the note actually points very strongly to personal reasons for his suicide and being in a depressed state of mind.

Druitt’s mother had been confined to an asylum in July 1888, following a serious bout of depression, which seemed to be aggravated by her husband’s death in 1885. It had been a suicide attempt, in 1888, which initiated the decision to place her in an asylum in Clapton, where she was certified insane. Her mental state had been exacerbated by her suffering from the, then untreatable, condition diabetes. This was, seemingly, hereditary in the Druitt family. It is an interesting point that whilst Druitt’s mother and an aunt attempted suicide, his maternal grandmother and his eldest sister both actually committed suicide. These were less enlightened times, as mentioned before, when the notion of suicide was seen as both a sign of weakness in person and, more specifically, mind. There were no support agencies to help cope with such desires, and no benevolent approaches from groups within authority to address such an issue. Druitt’s depressed mental state, in late 1888, could undoubtedly have been influenced by the prospect that he might end up as his mother had – either attempting suicide or being committed to a mental institution. Druitt’s case, in 1888, seems to highlight the extreme prejudice with which Victorian society viewed not only suicides, but also cases of mental infirmity, which today would be deemed as treatable. Such prejudices, then, could begin to explain the formulation of a familial suspicion against Druitt, although, how this gets linked with his potential for being the Whitechapel murderer is still far from clear.

An interesting aspect of Druitt’s professional life, in 1888, and one that might explain a lot of the events that surrounded his potential decision to commit suicide, is his second career. It has often been described by scholars on this subject that Druitt was a failed barrister. This, simply, is not the case. He actively maintained chambers at a practise address at No.9 King’s Bench Walk, in the illustrious Temple area of London, which was at the heart of the legal profession. Druitt had been active in highly demanding cases in the late 1880s, and seemed to show a tremendous degree of skill in successfully completing them. We must remember that he came from a semi-legal family and his older brother had a successful legal practice in Bournemouth.

One case that Druitt fought, in September 1888, during the Whitechapel murder scare, was at the Old Bailey itself. The case was one concerned with the malicious wounding of Peter Black by a former friend, Christopher Power, in the Kilburn area of London, in August 1888. Druitt, acting as defence counsel, realised the untenable nature of a ‘not guilty’ verdict based on the simple aspects of the case. Druitt instead pushed for a plea of insanity. He was also up against the formidable Charles Frederick Gill, acting for the prosecution as Senior Counsel for the Post Office, as there was evidence of some use of obscene letters by the accused.

With a great degree of skill and persuasive arguing, Druitt essentially ‘won’ the case with a successful ‘guilty, but insane’ verdict. Not only does this case, amongst the many others he fought during this period, show that Druitt was becoming a proficient and expert legal practitioner, he was also conducting this particularly stressful case during a period in which many have argued he could have been Jack the Ripper.

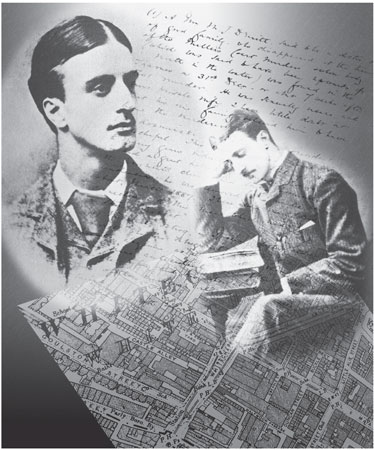

Montague John Druitt. (Moody/Morris Collection)

Druitt committed suicide in early December 1888. This is an obvious fact that we know about this rather enigmatic person, while there is a distinct dearth of knowledge about his private life, which mere speculation can only assume. However, there are rather telling features in the court case concerning, Christopher Power, in September 1888. The details of the case illustrated that the defendant Christopher Power was suffering some form of mental illness. This was affecting his work as a draughtsman and he was dismissed from his employment for ‘slackness’ and conflict with fellow workers in the same establishment. One of his colleagues, Peter Black – a former friend – Power later decided to attack both verbally, via obscene letters and innuendo, and ultimately violently by use of a knife. Obviously, without reference to elements of the Ripper case, let us restrict ourselves to Druitt’s personal world. The situation Power found himself in September 1888, in the mental aspect at least, was not unlike the situation Druitt would find himself in a few months later; which culminated in his suicide.

Power was eventually committed to an asylum, due to his ‘guilty, but insane’ plea that Druitt had worked for. Is it not possible that Druitt’s world was seemingly beginning to mirror Power’s in certain aspects, albeit without the obvious violent overtones? Certainly, as we saw earlier, Druitt did, as a matter of documented fact, believe his mental state was weakening for he left a note proclaiming so: ‘Since Friday I felt I was going to be like mother…’

We can speculate on the specific events that took place on that previous Friday, but it is more than possible it may have involved a visit to his mother, or some such related episode on behalf of his mother who was residing in an asylum in Clapton.

I would therefore say that Druitt was probably suffering from depression; a common reason for suicide. Of course, without the benefit of medical examinations and opinion (Druitt seems not to have been under any such observation) we can not be specific on his actual mental health in late 1888, but I do advance that he was suffering from depression, possibly aggravated by the sometimes extreme pressure on him from all areas of his life, not least a demanding and stressful career in the legal profession.

In the late nineteenth century the study of mental illness, despite the introduction of maiden treatments and continued academic discourse, was still in its infancy. We may wonder that in our ‘advanced’ age, the mysteries of the mind might still set us at the foothills of knowledge. For a man like Druitt, in 1888, engaged in a world of reputations and social climbing, maintaining a strict social contract, meant that he had to keep up appearances and take on responsibilities within a rigid class system, even at the acceptance of a relatively low-paid job at Mr Valentine’s educational institution. For men like Druitt status was all. Nevertheless, he would have felt that he had to traverse such a system to reach a position that gave him the social standing he needed and desired. As we have seen, a burgeoning legal career was growing into a very successful one by the end of 1888, allowing him to earn much more money than in his official job with Valentine. This may have caused friction with Mr Valentine, leading to an argument and ultimately his dismissal, made worse by his weakened mental state.

If we take into account the lack of support for those suffering from depression in Victorian London, coupled with the self-doubt a young man like Druitt would have had, we see the significance of his dismissal. It meant he was cut off from all he wanted to be. Before he was a peer and even influential amongst the Victorian elite and so his enforced ostracisation was the death knell to this depressed, young social climber. At the same time, Druitt could not have accepted such a course of action on his own; it was for others to initiate like his family and friends. In Druitt’s personal circumstances in 1888, although surrounded by copious work colleagues in his day-to-day activities, his eventual dismissal from Valentine’s school isolated him. This seems to be a more likely reason for Druitt’s suicide in late 1888. However, some still feel he could be Jack the Ripper because, as a suspect, he ‘was more likely than Cutbush!’

Begg, P., Fido, M. & Skinner, K.,

The Jack the Ripper A–Z

(Headline,1996)

Adrian Morris hails from Neasden in north-west London. He was born only a stone’s throw from Dollis Hill House, where both the great Victorian Prime Minister William Gladstone and the brilliant American writer Mark Twain once lived. He studied Political Science at Birkbeck College, London University, and has a long-standing interest in Irish history and post-1945 American history. He is a founding member of The Whitechapel Society and has been the editor of its journal since its modern inception in 2005.

Sir William Gull

M.J. Trow

‘Since every Jack became a gentleman, there’s many a gentle person made a Jack.’

(Shakespeare,

Richard III

, Act I, Sc. 3)

William Withey Gull was born aboard the

Dove

, a barge owned by his father, John, on the last day of 1816, while they were moored at St Osyth Mill, Colchester. John Gull was a wharfinger – a man who made his living ferrying cargo between Colchester and the Thames; William was the youngest of eight children. When he was four, the family moved to Thorpe-le-Soken in Essex. Within five years, John had died from cholera; a new epidemic sweeping London in those years.

It was William’s mother, Elizabeth, a devout and hardworking woman, who was responsible for her children’s education. She inspired her youngest to become a pupil teacher (one of the few ways upward for a working-class child), studying Latin and Greek. Through a local connection – Benjamin Harrison was a neighbour of the Gulls and Treasurer of Guys Hospital – the twenty-one-year-old joined the hospital as a medical student, with two rooms and a yearly income of £50.