Jane Austen For Dummies (45 page)

Read Jane Austen For Dummies Online

Authors: Joan Elizabeth Klingel Ray

Many an evening at home ended with an informal dance. Throw together a pianist, some people who like to dance, some people who like to watch, and â Violà ! â a dance was born! (For more details on dancing, see Chapter 5.)

As beautiful and luxurious as country homes were, people still liked to travel to visit friends and relatives and see new sites. And of course, sometimes people traveled for business, too. There were several ways to travel in Austen's day:

By foot:

By foot:

Austen and her friends thought nothing of traveling by foot. They frequently found themselves “crossing field after field at a quick pace, jumping over stiles and springing over puddles” as Elizabeth Bennet did when she made the three-mile walk from Longbourn to Netherfield (PP 1:7). (A

stile

is a set of three or four wooden steps built to help people over a wall or fence constructed in a field to keep animals enclosed.)

By coach:

By coach:

Horse-drawn carriages were the popular way to travel in Austen's day, but mostly the wealthier people had carriages because they were the only ones who could afford them. The Austens, themselves, gave up their carriage in 1798. People with titles, from knight up to the Royal Family, had their coats of arms emblazoned on their carriage doors below the windows. In

Persuasion,

William Elliot, heir to the Elliot Baronetcy, has the family arms on the door of his curricle, and Lady Russell, the widow of a knight, has his arms on her carriage (P 1:12, 2:5). Nothing like calling attention to yourself! (Read on in this chapter for models of carriages.)

By horse:

By horse:

Gentlemen rode horseback if they were traveling a short distance that was too long to walk but not long enough to ride in a carriage. And sometimes ladies, too, rode horseback, but normally just in the neighborhood. Jane Bennet in

Pride and Prejudice

takes a 3-mile horseback ride from her home to Netherfield because the Bennets' coach horses are being used on the farm â probably to pull wagons (PP 1:7). Ladies mostly took carriages and left the horseback rides to the men. Horses, like carriages, were not for those watching their money. When Willoughby plans to give a horse to Marianne, Elinor tells her she must not accept it on the grounds of expense â stable, hay, and groom to care for the horse (SS 1:12).

Roads in the period of Austen's novels were getting better than they had been because Parliament passed a series of acts to build and maintain turnpikes. Turnpikes were toll roads, with the tolls used to maintain the roads. As a result, people could travel long distances by carriage.

Many of Austen's characters travel in or drive various types of vehicles. People could own their own carriage or rent one. If the traveler had his own horses and was making an extralong journey, he could use them until the first stop; then, he would send his horses home and rent new horses for the next leg of the journey. Having a personal carriage showed you could afford it and signified status. Emma Woodhouse is upset that Mr. Knightley does not use his carriage much; in fact, he doesn't even keep carriage horses. So she is happy when she sees him in his carriage pulling up to the Coles' house for dinner: “âThis is coming as you should do . . . like a gentleman'” (E 2:8). It turns out that Mr. Knightley, ever the thoughtful gentleman, has used his carriage only so that it could be used to pick up poor Miss Bates and her niece, who have been invited for only the entertainment part of the evening. But many other Austen characters not only own carriages of their own, but actually use them. Austen deliberately assigns particular carriages to certain characters to make associations between the person and the carriage he drives, just as we might today characterize one person driving a cheap little car from another driving a large luxury auto.

One of the most popular carriages for travel was the chaise, which could hold up to four passengers, although it was a squeeze: The chaise had two seats, but it also had two extra seats that could be pulled out. The chaise was a closed carriage: It had a roof and doors, along with a place where packages and luggage (usually trunks) were strapped or “fastened” on the back (PP 2:15). Hand baggage could be stored within the passenger section. When Catherine Morland, Eleanor Tilney, and Eleanor's maid enter General Tilney's chaise to travel to Northanger Abbey, they see that “the middle seat of the chaise was not drawn out, though there were three people to go in it,” causing great crowding for the three passengers (NA 2:5). Instead of having a driver's box up front, the chaise was controlled by a

postilion

(or post boy, who sometimes wasn't a boy at all, but an adult male) riding the left of two horses pulling the vehicle. The “chaise-and-four” was a chaise drawn by four horses, and thus moved faster than the chaise drawn by two. A chaise-and-four could have as many as three postilions, one on each of the two lead horses, which were at the front of the chaise, and a third on one of the two “near wheel” horses, these being the horses next to either front wheel. As Catherine Morland looks out the window of General Tilney's chaise, she admires “the fashionable chaise-and-fourâpostilions handsomely liveried, rising so regularly in their stirrups” (NA 2:5). (“Liveried” means wearing distinctive uniforms.) Four horses also showed that the owner had money as it was expensive to keep horses. Plus, one had to pay those postilions! Because the chaise was a narrow vehicle, it did not tip over easily and thus was safer on the roads than wider vehicles. (Carriage accidents, where the carriage tipped over, were common; Austen's cousin Jane Cooper died in such an accident at age 28.)

Many of Austen's characters ride in chaises. In

Pride and Prejudice,

Bingley has a chaise-in-four, which is not surprising because he is very rich (PP 1:1). In

Sense and Sensibility,

Mrs. Jennings owns a chaise, and Mr. and Mrs. Robert Ferrars also travel by chaise (SS 2:3, 3:11). In the same novel, Willoughby uses a chaise to go from London to Cleveland in an attempt to see Marianne (SS 3:8). In haste to make the journey because he thinks Marianne is dying, Willoughby probably used a chaise-in-four for speed.

Mansfield Park

's Mr. Rushworth owns a chaise, though several of the guests at his wedding to Maria Bertram notice disparagingly that he hasn't bought a new one for him and his bride (MP 2:3). Lady Bertram's carriage in the same novel is also a chaise (MP 1:7). In

Persuasion,

“The last office of the four carriage-horses” owned by the vain and financially straitened Sir Walter Elliot is to draw the chaise that takes him to Bath when he leases his country estate to the Crofts (P 1:5).

The chaise was not the grandest vehicle, but it got its passengers where they needed to go. And with four horses mounted by liveried postilions pulling it, the chaise could look pretty good, as Catherine Morland notices in

Northanger Abbey â

even though she is squeezed in! Looking at all the examples of chaise owners in Austen's novels, you can tell that it was a popular vehicle.

A curricle was a light, two-wheeled carriage with a convertible top. Drawn by two horses, it was the snazzy sports car of the day, driven by its owner. It is not surprising that Willoughby, a devil-may-care hunk of a male, drives a curricle (SS 1:10). And the way he drives it tells a lot about him: “He drove through the park very fast” as he took Marianne for an all-day excursion (SS 1:13). Because the curricle was light, it tipped over easily and thus required good driving skills. So Willoughby was showing off.

Northanger Abbey

's Henry Tilney also drives a curricle, but he drives very “wellâso quietlyâwithout making any disturbance” (NA 2:5).

Persuasion

's Charles Hayter, another clergyman, also drives a curricle, and as a highly serious young man, he, too, shows no signs of driving like a show-off (P 1: 11). The curricle was the fashionable young man's vehicle, and like the sports car today, the way one drove it said different things about different drivers.

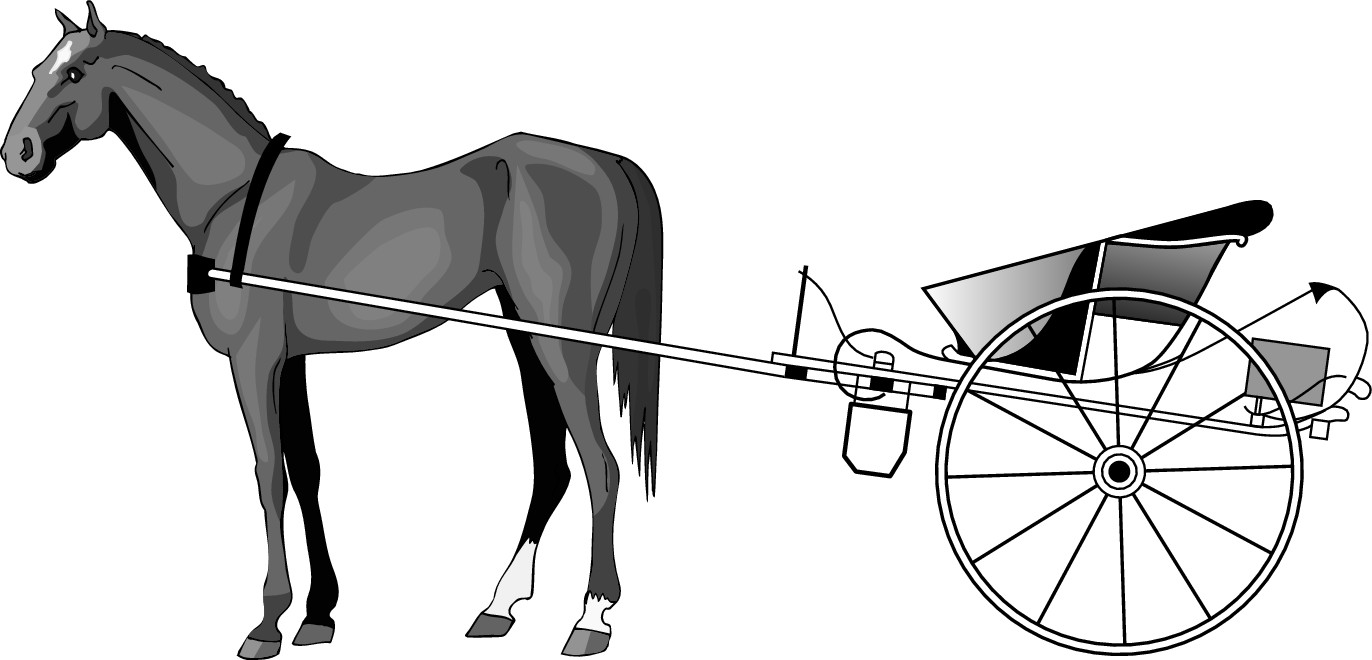

The gig (see Figure 11-2) was similar to the curricle, but it was cheaper to own as it required only one horse to draw it.

Northanger Abbey

's John Thorpe, who likes to think of himself as a snappy man about town, drives a gig. He would probably rather have a curricle, but he's short on cash and can only afford one horse. Like the curricle, the gig was driven by its owner. Thorpe, whip in hand, brags about how fast he drives and how well he controls his wild horse â though Catherine Morland notices when she goes with him that “the animal continued to go on in the same quiet manner, without shewing the smallest propensity towards any unpleasant vivacity” (NA 1:9).

Persuasion

's Admiral and Mrs. Croft drive a gig in a manner that reflects their marriage: They avoid the danger of hitting a post by Mrs. Croft's “coolly giving the reins [held by the Admiral] a better direction herself” (P 1:10).

Figure 11-2: |  |

The phaeton was also a light carriage pulled by one or two horses and used for pleasure driving. It had a convertible top. When Lady Catherine's daughter and her companion, Mrs. Jenkinson, pull up in front of Mr. Collins's parsonage, they're in a low phaeton, which they use to drive around Rosings Park (PP 2:6). A low phaeton had seats lower to the ground than a high phaeton, making the high phaeton more dangerous to drive as the height of the vehicle made it more likely to tip over. Mrs. Jenkinson must have been the driver. When Elizabeth's Aunt Gardiner learns of her niece's marriage to Darcy, she writes to her advising the purchase of a “low phaeton, with a nice little pair of ponies” for driving around the Pemberley estate (PP 3:10). In both cases of Austen's using phaetons, the passengers are ladies and their driving is in a restricted area: around the estate, rather than on public roads.

Another one-horse carriage was the chair. This light and agile vehicle appears only in Austen's fragment

The Watsons;

the Watsons own a chair because it's very inexpensive, and they're quite poor, living at the very lowest edge of genteel poverty.

The Watsons' chair shouldn't be confused with the sedan chair used in Bath: The sedan chair is a rickshaw-like enclosed chair with two poles, carried by two men, one at the front of the poles, another at the back of the chair holding the rear poles. If you visit the Pump Room in Bath, you'll see a sedan chair there, as well as at Number One, Royal Crescent. Sedan chairs were very popular in Bath during Austen's time, and there was even a sedan chair queue near the Royal Crescent that you can still see â minus the chairs â today: sort of the Regency version of a taxi stand. The sedan chair took its single passenger from one part of town to another and for no very great distance as men, rather than horses, provided the power. At the conclusion of her first assembly, Catherine Morland is carried home from the Upper Rooms in a sedan chair (NA 1:2).

Coaches were large vehicles that could hold six or more passengers, depending on the coach's size: Usually the coach had two rows of seats (each row held three passengers) facing each other, along with at least one side seat that pulled out. The coach was a strong, closed vehicle with front and back axles connected by a “crane neck” â a long curved iron bar. This bar also supported the body of the coach. The crane neck supposedly acted like springs to alleviate the bumpiness of the ride. Four horses pulled the coach, which had a driver's box at the front. The horses were controlled or driven by the coachman. The Bennets of

Pride and Prejudice

have a coach, as do the Musgroves of

Persuasion

(PP 1:7, P 1:11). Each is a large family and needs a large carriage to get around. With four horses needed to pull the coach, and a coachman to drive and maintain it, the owners showed they had the money to see to its upkeep. But the coach was also the most practical vehicle for a large family who could afford it.

Another four-horse vehicle was the chariot, holding four people facing the front, as opposed to facing opposite each other. The chariot was lighter than a coach and provided comfortable and speedy travel. John and Fanny Dashwood in

Sense and Sensibility

have a chariot, as does Mr. Rushworth's mother in

Mansfield Park

(SS 3:2, MP 2:3). The chariot was a classy vehicle, as appropriate for the wealthy Dashwoods as for the widowed, wealthy Mrs. Rushworth, who behaves with “propriety.”

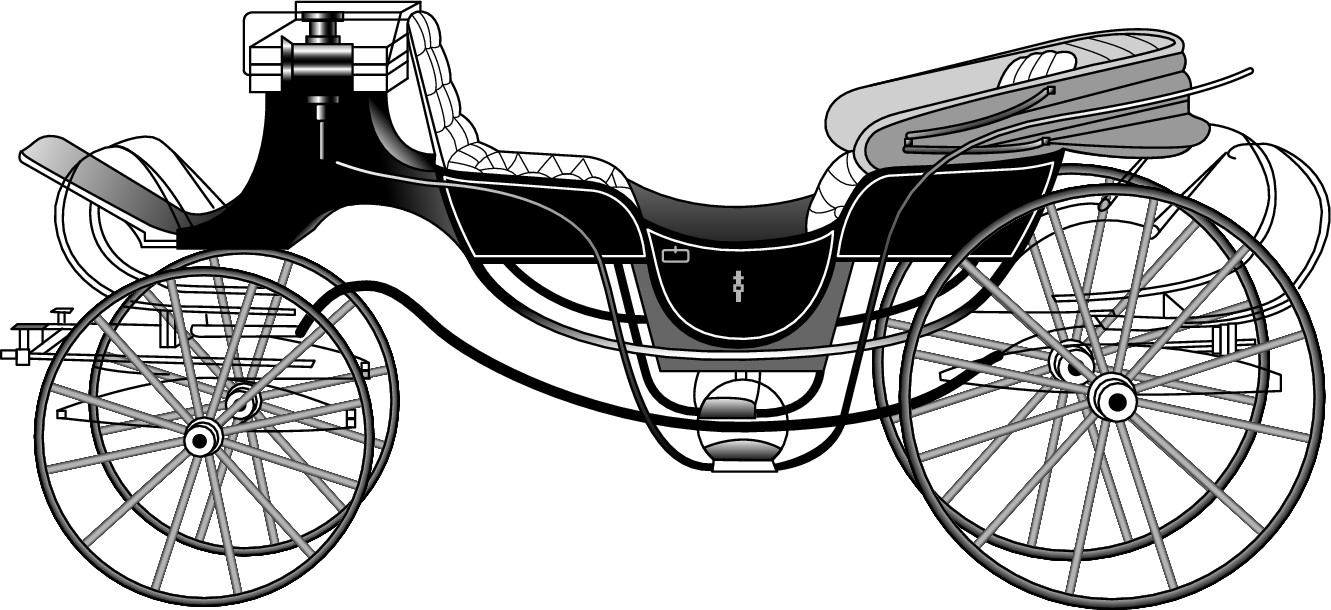

The most distinguished and showy of carriages was the barouche (see Figure 11-3) â a heavy vehicle drawn by four horses, but light-looking. The barouche had no storage box: Anyone who owned a barouche preferred having his luggage or purchases delivered! (Horse-drawn carts and even farmers' wagons served delivery purposes.) The barouche came in two models, the regular barouche and the barouche-landau. The barouche-landau's roof covered all four of the passengers, who sat facing each other as couples; the roof could also be arranged to cover just parts of the vehicle. In other words, the landau was the Regency's answer to the convertible car. The barouche's folding roof covered only the back part of the vehicle. But whatever the roof configuration, the barouche was the carriage of style. In

Persuasion,

the Dowager (widowed) Viscountess Dalrymple owns a barouche, as does

Mansfield Park

's eligible bachelor Henry Crawford (P 2:7, MP 1:8).

Henry drives his own barouche, seated in the barouche-box, which accommodated the driver and another person, for a total capacity of six. With its folding roof down, Henry's barouche is the perfect vehicle for the characters to use for their trip to Sotherton on a pleasant, warm day. While the barouche had no place for storage, Henry offers to pick up his sister's harp in his barouche: He could put it in the passenger area.

The Viscountess, as a lady, has a driver, so the three ladies who accompany her ride inside (for a total of four passengers).

Emma

's Mrs. Elton brags repeatedly of her in-laws, the Sucklings, who own a barouche-landau. Interestingly, there are a lot of other carriage owners in

Emma,

but their carriages are called simply that: carriages. Only the Sucklings' barouche-landau is mentioned by model name â and it's Mrs. Elton who mentions it over and over again!

Figure 11-3: |  |

So while you could drive only one other person in your gig, you could take the whole family plus their baggage and purchases in your coach.