Jesus Land (28 page)

Authors: Julia Scheeres

“But I’m a nice guy and making an exception for you,” he says.

I stare at my sneakers and wait for him to stop talking before turning to start down the driveway.

Three boys are pounding up the cement track as I jog downhill, including Boy 0, who staggers behind the others. The TKB group leader swoops past me on a moped and nips at his heels, trying to herd him up the hill, but he won’t speed up. His eyes, when he passes me, are dull, unseeing.

Bruce moves to the deck to continue his love story, looking up now and again to roar “faster!” but I can barely walk up the hill, much less run it. I pump my arms to make myself look faster, and it seems to work because he stops yelling.

At supper, I stare into my Velveeta casserole and wonder where I’d be right now if I’d run away with Scott. Staying with

his cousin in Kentucky? Living out of his car in Happy Hollow Park? In his backyard tent? We couldn’t hide forever.

After supper, Becky is teaching me to fold clothes when a whistle blows downstairs.

“Time for the meeting,” she says brightly.

I look at her warily.

“This isn’t a ‘special function,’ is it?” I ask, thinking about the “special function” boxing match.

“No, it’s Starr Family Unity,” she says. “It’s a good opportunity for you to get to know the other girls.”

She gives me permission to walk downstairs, enter the living room and sit on a metal chair. Everyone’s already there, arranged in a circle. Bruce sits across from me with his butt pillow. Beside him, RuthAnn embroiders a dish towel.

After I sit down, Bruce lifts his chin and peers around the circle.

“I’d like some water,” he announces.

Hands shoot into the air. “I’ll get it, Bruce!” “Oh, pick me!” “Please, Bruce, let me!” high voices plead.

I look around in disgust; even Susan’s hand is raised, although she waves it with a little less vigor than the others. Bruce considers each girl in turn, tapping an index finger against his mouth.

“Umm . . . Tiffany!”

The other girls fall back against their chairs in disappointment as Tiffany sprints to the kitchen. She returns carrying a tray with a single glass of water, smiling triumphantly. Bruce takes it from her without a word.

“Carrie, you start,” he says. “Tell Julia your story.”

Carrie inhales sharply and frowns down at her nails, but when she speaks, her words are loud and slow and clear:

“I smoked pot pretty much every day. I couldn’t stop. Got so bad I was getting high before church and flunking school.”

A drug addict?

! I look around the circle in astonishment, but no other face mirrors my alarm. I’ve never met a druggie before.

Janet’s next: “I snorted cocaine and hit my mother when she tried to take away my stash.”

Again, no one’s face registers alarm. One by one, the girls gaze into their laps and tell their stories. From their steady voices and polished lines, it’s clear they are called upon to do this often.

Tiffany: “I stole money from my parents to buy clothes. And sometimes I shoplifted.”

Rhonda: “I ran away from home and sold my body for money.”

A prostitute?! She’s not even sixteen.

When Susan’s turn comes, she glances at me, and her eyes now contain both shame and sorrow. She pulls at the hem of her T-shirt and mumbles something.

“What?” Bruce says loudly, cupping a hand behind his ear. “We can’t hear you!”

Susan pinches her lips together before speaking.

“I was a member of the Church of Satan,” she says mechanically. “I renounced Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior and bowed down to Beelzebub.”

I gasp.

A devil worshipper?

! I’d heard rumors of such activity back in Indiana, of animal sacrifice and orgies and possession by demon spirits.

But Susan seems so normal, so nice! How could she possibly choose Satan over Jesus Christ

?

I lean away from her and look around the circle; blank faces gaze back at me. I sweep my eyes back and forth across the orange and green tiled floor.

What am I doing here, among these criminals

? Something large screeches in the darkness beyond the patio door.

I am surrounded by danger. Tonight I’m to sleep in a roomful of druggies and whores and Satanists

! At least in jail, everyone had their own cage.

Bruce clears his throat, and I look up. All eyes are on me.

“So, what’s your story, Juliar?” asks Becky, sitting beside me. She smiles warmly. “What brought you to Escuelar Caribe?”

I study the floor, the traces of “Love’s First Blush” still stuck beneath my cuticles, the red high-tops Mother bought me at Kmart a few days ago, when I was still free. Bruce taps his foot impatiently.

“I . . .” I fall silent, wondering which “behavioral problems” my parents listed on the school application.

“I left home.”

“Correction!” Bruce says loudly. “You ran away.”

I stare at the tiny green seeds clinging to my shoelaces. Dominican seeds. I hate that term, “run away.” Dogs run away, people don’t. I walked away, slowly, deliberately, with a suitcase in each hand.

“Say it!” Bruce orders.

“I ran away.”

“What else?” he prods.

I shrug; those seeds are going to be a real pain in the ass to pick off.

“You drank alcohol,” Bruce volunteers.

“I drank alcohol,” I repeat, still staring at my shoes.

“You were an alcoholic.”

I jolt up my head. A drink now and then before school is not alcoholism.

“I was not!”

Bruce goes rigid on his butt pillow.

“Will you defy my authority?!” His voice booms off the flamingo pink walls. RuthAnn pulls a purple thread through her embroidery hoop, and in the abrupt silence you can hear the

sssss

of the silk slicing cotton.

Becky turns to face me.

“Juliar, admitting our faults is the first step toward recovery,” she says. “And confessing our sins is the first step toward forgiveness.”

“But I didn’t . . .” I start to protest, but stop short when I notice Bruce leaning forward with his hands planted on either side of his butt pillow, as if he were preparing to spring from the chair.

Don’t make a fuss, David said. Keep your head down.

I ball my hands into fists.

“I was an alcoholic.”

“What else?” Bruce demands, still on the edge of his seat.

I remember the word “condom” in the letter from my mother that Debbie had at the picnic table.

“I made love with my boyfriend.”

“You fornicated. You had unholy sex.”

I clench my fists tighter.

“I fornicated . . . I had unholy sex.”

“You were an alcoholic and a fornicator.”

“I was an alcoholic and a fornicator.”

I see Becky pat my arms with her hand, but I don’t feel her touch. My pulse pounds in my temples.

Boom boom boom

.

Bruce nods at me before saying “Let us pray.”

I bow my head and stare at my fists.

“Heavenly Father,” Bruce prays. “Thank you for bringing Julia to The Program. Please open her heart and her soul to receive Your rich blessings, and forgive her rebellion. Let her know how much You love her, and how much we do. In His name, Amen.”

When he finishes, Bruce stands, his palms lifted heavenward.

“Let us make a joyful noise unto the Lord!” he shouts.

Becky gives me permission to stand, then reaches behind her chair to pick up a guitar leaning against the wall. She strums it with twiglike fingers as we sing all five stanzas of “Kum Ba Ya,” each girl hugging herself tight and wailing at the floor.

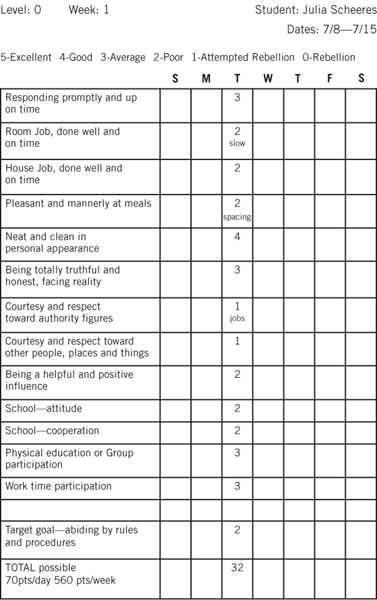

ESCUELA CARIBE

WEEKLY RECORD OF POINTS

Life becomes a loop of school, chores, and punishment.

All the things I took for granted just last week—listening to the radio, talking on the phone, or simply walking into a bathroom and closing the door behind me—seem like a wonderful dream. I never knew how good I had it, even when I was eating off room service trays at Howard Johnson’s.

Bruce stops explaining my housework deficiencies, and simply goes about destroying my work.

“Wrong,” he says, as he upends a drawer of clothes onto the floor.

“Wrong,” as he rips the foam pad off its frame.

“Wrong,” as he tears clothes from hangers.

Afterwards, he studies my face for signs of disrespect, but I’ve learned to hide them well; my brain curses him out even as my mouth apologizes for my inadequacy.

When he tells me to get down and do push-ups, I dip low and count loud.

When I finish hauling the rock pile to the driveway and he orders me to move it back downhill, I say, “Yes, sir, right away.”

When he’s thirsty or he sneezes, I join the “me, me, me” chorus for the privilege of fetching him water or Kleenex.

I have gotten with The Program.

As I haul rocks, run casitas, and scrub toilets, I’ve got a big “fuck you” smile on my face. It scores me high points in the Courtesy and Respect Toward Authority Figures box. Academics are another area where I shine. School is easy when you have a compelling reason to pay attention.

David and I develop a code language to check in on each other when no one’s watching:

An upward jut of the chin means “How are you doing?”

A shrug: “As good as can be expected.”

A nod: “Okay . . . for the moment.”

A head shake: “Bad.”

Raised eyebrows: “You don’t look too hot” or, when something weird happens, “Can you believe this?!”

A combination of crossed arms and a loud sigh: “I hear ya. Hang in there.”

Once when I was having a particularly rotten day and arrived at school snot-faced and raw, he left me a yellow hibiscus on Starr’s picnic table. I watched him from where I stood in a doorway, waiting for permission to cross the courtyard to my next class. There were a lot of people milling about, and nobody noticed when he laid the flower at my place at the table. Hibiscus, a Florida flower.

I wore it in my watchband until Debbie said it looked like I was wearing jewelry—a privilege I haven’t earned—and told me to take it out. By then, half the petals had fallen off, but I pressed it inside my Geography book anyway.

At Starr, Tiffany narks and brown-noses her way to the top of the trash heap and becomes high-ranker. She ratted out Janet for sneaking a piece of bread between meals because she was hungry, Susan for using a kitchen rag to clean the dormitory, and Carrie for yelling “shit!” when she jammed her thumb during dodgeball—that’s what got Carrie demoted from the top spot.

That’s how The Program works. Snitch on people, and you score big in the Being a Helpful and Positive Influence box. Susan is the only girl I trust; I avoid the others as much as possible. You never know who will betray you.

After she busted Susan, Tiffany walked into the bathroom as I was scrubbing the toilets, and I glared at her in the mirror.

“Live and let die,” she said, bending back the tip of her cheerleader nose to check for buggers. She now spends all her time primping—rubbing sugar into her face and lemon into her hair and filing her toenails—in preparation for her release.

“I’ll be playing tennis at the Hartford Country Club next month while the rest of you rot down here,” she said, picking up a bar of soap and streaking it over my clean mirror.

By the time I realized what she’d done and scrambled to my feet, she was already out the door, flashing a fake smile.

On Saturday, Starr takes a field trip to a waterfall on the outskirts of Jarabacoa. We drive through the center of the village— past plywood shacks and trash fires and open sewers and malnourished children with swollen bellies and blond-streaked hair and women carrying baskets on their heads and men who yell “Americanas!” at us—and bump up a narrow dirt road until we reach a dead end. S

ALTO DE

J

IMENOA

says a hand-painted sign at the edge of the jungle.

We line up by rank outside the van and Bruce leads the way up a muddy path as the dense vegetation whirs with hidden birds and insects. Above us, the sapphire sky glitters through the high lattice canopy and the smell is green and living. The steamy air clings to us as we brush past giant ferns, and for a few moments I forget where I am and feel excited about being in a foreign country.