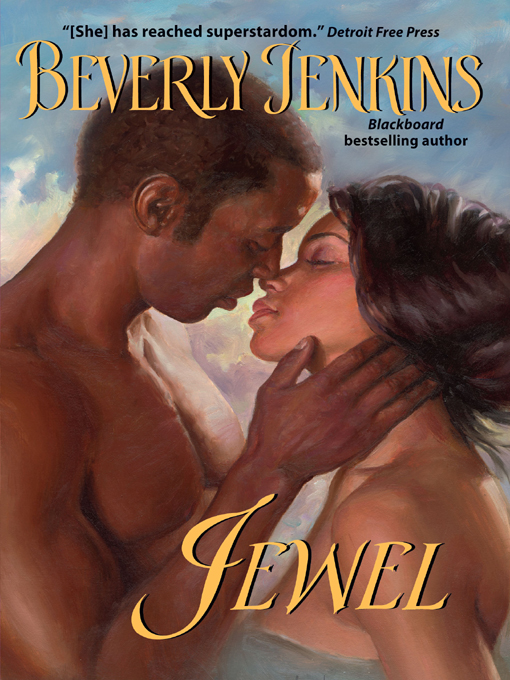

Jewel

Authors: Beverly Jenkins

Jewel

To my mother-in-law,

Joy L. Kelley,

my own Abigail

Prologue

Cecile was furious. The doddering old reprobate she’d stooped to…

Chapter 1

Surrounded by the Eden-like green of the countryside, Eli Grayson…

Chapter 2

It was wash day, and a weary Jewel Crowley was…

Chapter 3

Outside, they walked over to the buggy. Jewel had steam…

Chapter 4

“I now pronounce you man and wife.”

Chapter 5

Once all the holes were dug, Maddie headed off to…

Chapter 6

Intent upon on following G.W.’s advice, Eli walked down to…

Chapter 7

After dinner, Jewel and Anna helped Abigail gather up the…

Chapter 8

The next morning, Jewel fixed breakfast for her brothers, and…

Chapter 9

Silent, they drove through the night. Under the pale moon…

Chapter 10

As Jewel rode to church with Eli Sunday morning, she…

Chapter 11

The chirps of birds greeting the dawn roused Jewel from…

Chapter 12

After completing the town business for the day, Eli left…

Chapter 13

Eli awakened to the smell of bacon frying. Wondering why…

Chapter 14

Two weeks later, on a beautiful early June afternoon, the…

Chapter 15

Eli and G.W. were in the Gazette office the following…

Chapter 16

Jewel was missing Eli something fierce. For the last few…

Chapter 17

Jewel awakened the next morning and sure enough, she was…

May 3, 1881

Boston

C

ecile was furious. The doddering old reprobate she’d stooped to marry two weeks ago in order to get at his supposed fortune was in reality as poor as he was ancient. His name was Lucius Briles, and lying beneath him on their wedding night, while he grunted and pushed and ran his crone-like hands over her naked flesh, had forced bile into her throat, but she’d sent her mind elsewhere until he was done, confident riches would be her reward. However, her talk with his barrister yesterday revealed that his wealth was a façade. The fine Boston mansion, the carriages, the china and sparkling silverware all belonged to the bank, which planned to begin foreclosure proceedings in a few days. Everything from horses to candlesticks would be sold, leaving the newlyweds with no alternative but to reside with his dog-faced daughter, Bethany, a woman who’d disliked Cecile on sight and had done everything in

her power to keep the nuptials from taking place. Cecile now wished she’d not dismissed Bethany so out of hand. Lucius Briles was not the man she’d thought him to be, and because of that, she would have to vanish as she always did after a successful fleecing, only this time there’d been no fleece, just a nasty old man who wanted to put his hands up her skirt.

Her anger knew no bounds as she paced the confines of her well-appointed bedroom. How was she supposed to survive without money for new gowns, hairdressers and the like? She’d made a good living these past six years marrying wealthy men and then absconding with their riches. Briles was just the latest in a long line of the many, but the first to not have a pot to piss in or a window to toss it out of. She faulted herself for not spending more time studying him before making her play for his affections. The local newspaper had portrayed him as a pillar of Boston’s representative society, a man of such wealth and stature the great Fred Douglass himself had once dined at the Brileses’ table. She’d taken the information as gospel not knowing Briles was in hock up to his ear trumpet and smelly wooden teeth.

She’d been in Boston six weeks now and had journeyed to the city in order to escape the Pinkertons sicced on her by her last husband, a San Francisco businessman named Frank Sorrell. She’d stayed married to Sorrell just long enough

to worm her way into his bed, heart, and bank accounts before disappearing. Frank had been quick, though; the Pinkerton he’d hired caught up with her at the train station a few days later and she’d had to bed the detective in order to wiggle free. When he awakened the next morning to find her gone, along with his wallet, she was certain he’d not been happy, but she’d wanted payments for her services and felt it only right.

Upon arriving in Boston, her plan had been to find another mark, relieve him of his funds, and take a steamer to Canada hoping the Pinkertons would give up the chase and go after other prey, but at the moment she didn’t have enough money to get her anywhere.

So now, she looked around the bedroom in search of items she could pawn. It didn’t matter that everything in the house belonged to the bank, she had a more pressing need. To that end, she opened the trunk she’d dragged out of the attic and began to fill it with whatever she could find: heavy ornate candlesticks, the silverware from her morning meal, she even took down the framed portraits of Lucius and his first wife hanging in the hallway because the frames looked valuable. The cache wasn’t nearly enough, but she’d search the rest of the house in a few moments. Now she had to finish her packing, so she began removing her gowns from her wardrobe.

“Leaving?” The smug voice belonged to the dog-faced daughter, Bethany.

Cecile didn’t turn around. “I’m going to visit a cousin in New York.” She continued removing her gowns from the armoire. “And well-brought-up women do not enter a room without announcing themselves first.”

“What would you know about the habits of well-raised women?”

“Enough to know that you are not.”

“Neither are you, according to the wire I received today from a Pinkerton.”

Cecile paused but only for a moment, then began placing her face paints into a small carpet-bag. “Have you been fabricating tales, Bethany? I know you’ve never cared for me, but Pinkertons? That’s a bit over the top even for you.”

“According to the wire, fabrications aren’t needed. Pinkertons have been trying to run you to ground for years. Apparently you make your living preying on men like my father.”

“I’ve no idea what you’re babbling about.”

“No? Then maybe when the man arrives he can voice it in a language you do understand.”

“What man?”

“The Pinkerton. He’ll be coming here later and is very interested in speaking with you.”

Cecile’s mind was racing beneath her cool, distant exterior. “About what?”

“The other men you’ve embezzled.”

“You’re babbling again, Bethany.”

“I think not. When you first began showing an interest in my father I sensed something wasn’t right. An acquaintance suggested I share my fears

with Pinkertons’ Boston office and I did. They made some inquiries on my behalf, and lo and behold a woman fitting your description turned up in their arrest sheets.”

“There are thousands of women fitting my description all over the country.”

“But none make their living by marrying multiple husbands and stealing from them.”

Cecile didn’t care for the superior haughtiness flashing in Bethany’s basset brown eyes any more than she liked hearing that she might be heading for arrest. On the pretext of placing her nightclothes in the trunk, Cecile walked over to it and wrapped her hand around one of the heavy candlesticks hidden beneath her gowns. Employing a trick as old as Methuselah, she trilled, “Well, hello, Lucius.”

When Bethany turned to the door expecting to see her father, Cecile brought the candlestick down on the back of her head with such force she fell to the floor. Cecile struck her again to make sure she was dead. Staring down at the pool of blood spreading slowly beneath Bethany’s head, Cecile felt the glow of satisfaction. “Had you been smart, my dear stepdaughter, you would have kept your mouth shut and left me unawares of the Pinkerton’s interest. Instead, you had to gloat and tell all. Now look at you. Those nasty little puppies you call children are going to be motherless, all because you couldn’t stand not throwing up what you knew in my face. Stupid.”

It came to Cecile that she had been stupid as well. Murder was a very serious offense. Had she been thinking, she would have struck Bethany only hard enough to render her senseless, tied and gagged her and stuffed her in a closet somewhere. Instead, she’d killed her. Now she was really going to have to go to ground, and in a place no one, not even the Pinkertons, would think to look. While she thought about where that might be, she quickly changed into the widow’s weeds she always traveled in.

Everyone treated widows with deference. Men opened doors, gave her their seats. A few had even purchased train tickets for her when she claimed to have lost her own due to the stresses brought on by grief. It was the ruse she’d have to employ now because she had no time to pawn anything and it was imperative that she get on a train and leave Boston immediately. Not knowing when the Pinkerton planned to arrive, or if he were already secreted outside watching the house, made her exit a risky one, but she had no choice.

Adjusting her veil, she straightened her rustling silk skirt and picked up her black handbag. All of her glorious gowns and other personal items would have to be left behind. She’d have to travel light, but was confident in her abilities to play on the kindness of strangers in order to take care of her immediate needs. Looking down at Bethany’s dead dog-face one last time, she stepped over the body and left the room. Walking quickly down the hallway to the stairs that led to the front

door, she’d decided where she’d go. She’d spend a month or so making sure she wasn’t being tailed, then she’d head back to the place where all her marriages began. Grayson Grove. She wondered if Nate and Eli Grayson would be glad to see her? Smiling at her own cleverness, she closed the door and set out for the train station.

Grayson Grove Cass

County, Michigan

May 3, 1881

S

urrounded by the Eden-like green of the countryside, Eli Grayson drove his horse-drawn wagon down the bumpy road toward town. Towering trees wearing the first fresh leaves of spring lined his passage and drew the eye up to a cloudless blue sky. Birdsongs filled his ears while the warmth of the early May breeze made the harsh raw winds of winter just a memory.

Eventually the road led out of the trees and into the sunlight and the landscape gave way to meadows filled with blooming wildflowers spread out like God’s opened paint box. Taking in the beautiful vista, Eli knew of no other place he’d rather be than Grayson Grove. It was established in the 1830s by his grandparents who’d come from Carolina to what was then the Michigan Territory. Armed with their freedom papers

and money enough to purchase land, courtesy of their dead master’s will, they and the thirty other freed slaves who’d accompanied them founded the settlement Eli’s grandmother Dorcas christened Grayson Grove.

Over the years the number of Grove residents had increased, making the settlement now a township, one of three all-Black townships in Cass County.

Back then, the only business in the clearing that became the town’s center had been the Grayson General Store. Now, as Eli made his way down Main Street, in addition to the long-established Vern’s Barbershop, Bates Undertaking, and the Grayson livery stood the doc’s office operated by Eli’s cousin-in-law, Dr. Viveca Lancaster Grayson. Other new enterprises serving the Grove were the seamstress shop run by Adelaide Kane, and the Grayson Lending Library founded a few years back by lifelong family friend Maddie Loomis. Nestled next to the library was the boarded-up storefront that once housed the town’s newspaper, the

Gazette

. As founder and editor, Eli had worked tirelessly for nearly a decade to publish a paper the area could be proud of, but as the bigger nationally syndicated papers began to encroach on his territory, he had little money to invest in new presses or salaries to hire additional help in order to compete. He’d taken out bank loans and borrowed money from friends and family, all in an effort to keep the paper afloat, but last year he’d faced reality. Not only were his bank notes

overdue, he couldn’t repay his friends. Granted they knew he’d eventually make good on the debts, but he didn’t know when, or how.

So, he sat on the wagon seat staring at what had once been his life’s blood. It was his plan to reopen the newspaper, but like the repayment of his debts he had no idea how or when. Sighing with frustration, he took one last look at his boarded-up dreams then continued down the street to the general store.

For such an early hour, there were quite a few buggies and wagons tied up near the businesses he passed. Some of the people on the walks waved to him and called out, “Morning, Eli.”

He waved back, sending them his patented grin. All were friends and neighbors, and each face represented a memory of growing up—like Mr. Welch, whose apples he used to steal, and Mrs. Potts, who used to rap him across the knuckles with a wooden ruler whenever he pulled some prank in school or forgot his homework. In spite of the uncertainties Eli faced with the

Gazette

, he loved the Grove and after having traveled all over the nation, it was still the only place he cared to be.

Miss Edna Lee had been running the general store since Eli was in short pants, and no one was kinder. Although she was in her sixties now and slowing down a bit, the New Orleans–born octoroon had aged beautifully and was, like all the other women in the Grove, smart as a whip. “Morning, Eli,” she called out cheerily as the tin

bell above the door announced his arrival. Her long silver hair was braided into two long plaits and secured low on her neck, another Miss Edna fixture.

“Morning, Miss Edna.”

A chorus of greetings from the customers inside buying tools, farm implements, and other necessities also marked his entrance. He got a nod from the store’s regulars, who were drinking coffee and watching the morning’s checker game.

“When’s Nate and the doc due back?” Aaron Patterson asked as he kinged his opponent, his twin brother Abraham, now scowling from his seat on the other side of the black-and-red board perched on top of an old cracker barrel.

Nate Grayson was Eli’s cousin. He was also the Grove’s mayor and sheriff. The doc was his wife, Viveca. “Not for another month,” Eli answered, taking his coffee mug down from where it hung on the pegboard near Edna’s front counter. Most of the adults in the Grove had a mug hanging in the store. Nate and Viveca were in California visiting her parents. With them on the trip were their fourteen-and fifteen-year-old daughters, Magic and Satin, and their twin sons, four-year-old Jacob and Joseph.

Eli poured the dark brew Miss Edna always kept hot no matter the season into his cup and added, “The way Viveca’s mama loves her grandchildren, it may be years before she lets them come home again.”

Everyone nodded in agreement. They’d met Mr. and Mrs. Lancaster when they’d visited the Grove five years ago. Francesca Lancaster had as much an irrepressible spirit as her fearless doctor daughter.

The Grove general store also served as the post office. Miss Edna handed him a few envelopes. “These came in last evening.”

“Thanks.” With his coffee mug in hand and the mail tucked into the pocket of his worn blue cotton shirt, Eli called out his goodbyes, waved, and walked down to the mayor’s office. He’d been asked to look after the Grove’s business matters while Nate was away.

Inside the office, he sat at the desk, and while sipping at the best coffee in the state, scanned the mail. Most of the envelopes addressed to Nate held items like land deeds and notices from the state’s capitol on upcoming or recently passed laws. Nothing in the correspondences appeared to need immediate attention, so he added them to the pile on the desk. There were also a couple of letters for Viveca. One, from her missionary sister Jess in Liberia, he tucked into the top desk drawer for safekeeping. At the bottom of the stack was a letter addressed to Eli. He didn’t recognize the New York return address, but opened it and quickly read the hand-penned page inside. The more he read, the wider his eyes became. Excited, he read it again to make sure of the wording, then he tossed the letter in the air and shouted for joy.

The letter was from G. W. Hicks, owner of the largest Black newspaper syndicate in the country. Hicks was interested in adding the

Gazette

to his holdings, and he was coming to the Grove to speak with Eli about the idea! Eli wanted to dance on the desk, do handsprings, do cartwheels. Hicks had a sterling reputation. With his backing the

Gazette

could go far. Picking up the letter he read it again and this time looked for the date Hicks planned to arrive. Eli checked the calendar on the desk and his eyes widened again. Mail delivery was always slow in the Grove and in this instance it had been remarkably so. Hicks was due to arrive tomorrow on the ten o’ clock train from Detroit! Draining the rest of his coffee, Eli hastily left his cousin’s office and locked up. Filled with heart-pounding excitement, he all but ran down the walk to the

Gazette

’s office to get it ready for Hicks’s visit.

It was dark inside and after a year of being boarded up the dust in the air could be seen against the slat of sunlight coming in through the opened door at Eli’s back. Back when he’d closed the place the costly glass windows that had fronted the establishment were taken down and stored, and plywood nailed up over the openings. Looking around now, he wished he could put the panes back in, but there wasn’t time. The plywood probably wouldn’t make a good first impression, but if he took it down and it rained, the ancient press might be ruined and that would be even worse. His only option was to sweep the floors,

get rid of the dust, and hope that if he brought enough lanterns along tomorrow Hicks could see the layout inside.

Vernon Stevenson, owner of the barbershop and godfather to Nate’s daughter, Magic, wandered in. “What’re you doing, Eli?”

He explained and a grin split the barber’s face as he hooted, “Hot damn! That’s good news. Be nice to have the

Gazette

going again. You planning on cleaning the place up?”

Eli nodded while wondering if mice had gotten in over the winter.

“Be glad to lend a hand if you need one. No customers at that moment. I’ll grab some brooms.”

By later that morning the news that Eli was expecting an important visitor who might help him reopen the

Gazette

spread across the Grove. It also brought volunteers to help with the cleaning, among them his mother, Abigail, and her husband, the irascible old lumber beast Adam Crowley.

“Is it true, Eli?” his mother asked excitedly as she moved into the doorway aided by her carved ebony cane. “G. W. Hicks wants to buy the

Gazette

?”

Eli greeted his mother with a smile. “Not sure about the buying, but he might be interested in adding us to his syndicate.”

Pleased, Adam nodded. “Be a good thing.”

“Yes it would be.” They stepped outside so he could talk to them and not be in the way of the sweeping.

Abigail searched her son’s face. “Adam and I truly hope this will be the offer we’ve all been praying for.”

“Even if you are a Democrat,” her husband tossed out with a grin, arms crossed over his massive chest.

The topic of Eli’s political affiliation was a never-ending, yet friendly, debate between the two men. “Everybody’s going to be a Democrat before long, Adam,” Eli pointed out confidently. “You’ll see.”

“Not while I’m living.”

Eli counted himself amongst the small but rising number of Black men registered to vote as Democrats. With the majority of the race still in the pockets of what the national press called the Lily White Republicans, Eli and other like-minded individuals were showing their disillusionment with the party of Lincoln and its increasing refusal to back issues most important to its Black constituency by aligning themselves with the much-hated Democrats. Of course, he had nothing but contempt for the southern members of the party who’d rather commit murder than allow Black men to vote, but the Republicans were taking Black votes for granted. Something had to be done to shake them up, and Eli and the other Black Democrats hoped this would be a way to bring that about. “Adam, if all men of good conscience would just consider…”

Abigail held up a hand. She’d heard this argu

ment a hundred times before. Looking pointedly between the two men she loved best, she stated, “You two can pick up this eternal argument at another time. G. W. Hicks is the topic for now. When will he arrive?”

Eli grinned at Adam. Although Abigail would never admit it, she was as irascible as her husband. “Tomorrow’s train.”

“How long do you think he’ll stay?” Adam asked.

Eli shrugged. “But I’ve talked to the Quilt Ladies. They’ll be putting him up while he’s here.”

The Quilt ladies were the self-appointed moral society of the Grove and the owners of the best boardinghouse and dining room in the area.

“He’ll enjoy that,” Abigail added. “Caroline and her ladies can be harpies sometimes, but they run a fine house.”

A short while later, the work was done. Eli thought everything looked fine and hoped Hicks would agree.

After having dinner with Abigail and Adam, Eli went home to his small cabin and dug out the

Gazette

’s ledgers, along with some of the old copies of the paper he’d saved and his subscription lists. He was sure Hicks would want to review the financial aspects of the operation, so he planned to have them available.

At the height of the

Gazette

’s popularity, there’d been subscribers as far west as Chicago and as far north as Muskegon. The Detroit area had its

own Black papers, very popular papers, but the

Gazette

had a few subscriptions on that side of the state as well. Then, after his funds ran out, he had nothing. No subscribers, no newspaper. Hicks was supposed to be a man of vision. Eli hoped it was true because reopening the

Gazette

would put purpose back into his life.

It hadn’t always been that way, though. In fact it had taken him quite some time to figure out what to do with his life because, as a young man, chasing women had been his one and only passion. On many occasions his mother had accused him of being too handsome and too arrogant for his own good, and she’d been correct. Every scrap of trouble he’d ever gotten himself into had been because of his affinity for the softer sex. Back then he’d juggled women like a performer in a circus act with mistresses in Kalamazoo, Niles, Muskegon and one particularly talented brown-skinned beauty across the lake in Chicago. Filled with hubris he’d even committed the cardinal sin of sleeping with Nate’s first wife, Cecile, while Nate was away fighting Lincoln’s war. All their lives they’d been close as brothers, but after Nate learned the adulterous truth, Cecile was sent packing, divorce papers in hand, and Eli? Nate refused to speak to him, or acknowledge his presence. As far as Nate was concerned Eli no longer existed.

Eli dropped his head into his hands at the painful memory. The guilt and shame had been so much he’d turned to the bottle, becoming pariah

to both family and friends. Although the liquor had him convinced that being an outcast hadn’t mattered, it had.

Then, five years ago, Dr. Viveca Lancaster blew into the Grove like a western cyclone. After the dust died, she and Nate had fallen in love, and Eli and Nate began taking small steps toward reconciliation. Eli doubted Nate would ever fully forgive him, nor would Eli ever forgive himself, but the cousins were closer now than they’d been in a long while and were pleased with the healing of the rift everyone in the Grove thought permanent.

With that episode no longer coloring every aspect of his life, he was doing his best to stay on the straight and narrow. Being the publisher and editor of the

Gazette

had been instrumental in helping him achieve that. Now having caught the attention of G. W. Hicks the future looked bright.