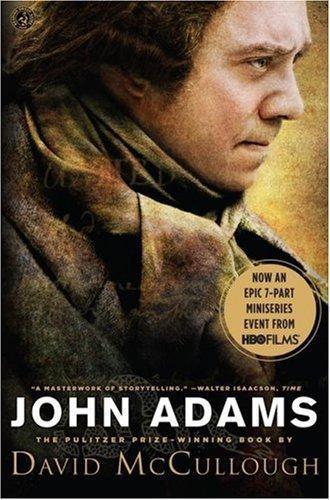

John Adams - SA

Authors: David McCullough

Tags: #Presidents & Heads of State, #Presidents, #United States - Politics and Government - 1783-1809, #Presidents - United States, #General, #United States, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #19th Century, #Historical, #Adams; John, #Biography & Autobiography, #United States - Politics and Government - 1775-1783, #Biography, #History

eText version 2.0

by

David McCullough

For our sons David, William, and Geoffrey

PART I: REVOLUTION

Chapter One: The Road to Philadelphia

Chapter Two: True Blue

Chapter Three: Colossus of Independence

Chapter Four: Appointment to France

Chapter Five: Unalterably Determined

Chapter Six: Abigail in Paris

Chapter Seven: London

Chapter Eight: Heir Apparent

Chapter Nine: Old Oak

Chapter Ten: Statesman

Chapter Eleven: Rejoice Ever More

Chapter Twelve: Journey's End

PART I: RevolutionWe live, my dear soul, in an age of trial. What will be the consequence, I know not.

—John Adams to Abigail Adams, 1774

But what do we mean by the American Revolution? Do we mean the American war? The Revolution was effected before the war commenced. The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people.

—John Adams

CHAPTER ONE: THE ROAD TO PHILADELPHIAI have heard of one Mr. Adams but who is the other?

—King George III

You cannot be, I know, nor do I wish to see you, an inactive spectator. We have too many high sounding words, and too few actions that correspond with them.

—Abigail Adams

IN THE COLD, nearly colorless light of a New England winter, two men on horseback traveled the coast road below Boston, heading north. A foot or more of snow covered the landscape, the remnants of a Christmas storm that had blanketed Massachusetts from one end of the province to the other. Beneath the snow, after weeks of severe cold, the ground was frozen solid to a depth of two feet. Packed ice in the road, ruts as hard as iron, made the going hazardous, and the riders, mindful of the horses, kept at a walk.

Nothing about the harsh landscape differed from other winters. Nor was there anything to distinguish the two riders, no signs of rank or title, no liveried retinue bringing up the rear. It might have been any year and they could have been anybody braving the weather for any number of reasons. Dressed as they were in heavy cloaks, their hats pulled low against the wind, they were barely distinguishable even from each other, except that the older, stouter of the two did most of the talking.

He was John Adams of Braintree and he loved to talk. He was a known talker. There were some, even among his admirers, who wished he talked less. He himself wished he talked less, and he had particular regard for those, like General Washington, who somehow managed great reserve under almost any circumstance.

John Adams was a lawyer and a farmer, a graduate of Harvard College, the husband of Abigail Smith Adams, the father of four children. He was forty years old and he was a revolutionary.

Dismounted, he stood five feet seven or eight inches tall—about “middle size” in that day—and though verging on portly, he had a straight-up, square-shouldered stance and was, in fact, surprisingly fit and solid. His hands were the hands of a man accustomed to pruning his own trees, cutting his own hay, and splitting his own firewood.

In such bitter cold of winter, the pink of his round, clean-shaven, very English face would all but glow, and if he were hatless or without a wig, his high forehead and thinning hairline made the whole of the face look rounder still. The hair, light brown in color, was full about the ears. The chin was firm, the nose sharp, almost birdlike. But it was the dark, perfectly arched brows and keen blue eyes that gave the face its vitality. Years afterward, recalling this juncture in his life, he would describe himself as looking rather like a short, thick Archbishop of Canterbury.

As befitting a studious lawyer from Braintree, Adams was a “plain dressing” man. His oft-stated pleasures were his family, his farm, his books and writing table, a convivial pipe and cup of coffee (now that tea was no longer acceptable), or preferably a glass of good Madeira.

In the warm seasons he relished long walks and time alone on horseback. Such exercise, he believed, roused “the animal spirits” and “dispersed melancholy.” He loved the open meadows of home, the “old acquaintances” of rock ledges and breezes from the sea. From his doorstep to the water's edge was approximately a mile.

He was a man who cared deeply for his friends, who, with few exceptions, were to be his friends for life, and in some instances despite severe strains. And to no one was he more devoted than to his wife, Abigail. She was his “Dearest Friend,” as he addressed her in letters—his “best, dearest, worthiest, wisest friend in the world”—while to her he was “the tenderest of husbands,” her “good man.”

John Adams was also, as many could attest, a great-hearted, persevering man of uncommon ability and force. He had a brilliant mind. He was honest and everyone knew it. Emphatically independent by nature, hardworking, frugal—all traits in the New England tradition—he was anything but cold or laconic as supposedly New Englanders were. He could be high-spirited and affectionate, vain, cranky, impetuous, self-absorbed, and fiercely stubborn; passionate, quick to anger, and all-forgiving; generous and entertaining. He was blessed with great courage and good humor, yet subject to spells of despair, and especially when separated from his family or during periods of prolonged inactivity.

Ambitious to excel—to make himself known—he had nonetheless recognized at an early stage that happiness came not from fame and fortune, “and all such things,” but from “an habitual contempt of them,” as he wrote. He prized the Roman ideal of honor, and in this, as in much else, he and Abigail were in perfect accord. Fame without honor, in her view, would be “like a faint meteor gliding through the sky, shedding only transient light.”

As his family and friends knew, Adams was both a devout Christian and an independent thinker, and he saw no conflict in that. He was hard-headed and a man of “sensibility,” a close observer of human folly as displayed in everyday life and fired by an inexhaustible love of books and scholarly reflection. He read Cicero, Tacitus, and others of his Roman heroes in Latin, and Plato and Thucydides in the original Greek, which he considered the supreme language. But in his need to fathom the “labyrinth” of human nature, as he said, he was drawn to Shakespeare and Swift, and likely to carry Cervantes or a volume of English poetry with him on his journeys. “You will never be alone with a poet in your pocket,” he would tell his son Johnny.

John Adams was not a man of the world. He enjoyed no social standing. He was an awkward dancer and poor at cards. He never learned to flatter. He owned no ships or glass factory as did Colonel Josiah Quincy, Braintree's leading citizen. There was no money in his background, no Adams fortune or elegant Adams homestead like the Boston mansion of John Hancock.

It was in the courtrooms of Massachusetts and on the printed page, principally in the newspapers of Boston, that Adams had distinguished himself. Years of riding the court circuit and his brilliance before the bar had brought him wide recognition and respect. And of greater consequence in recent years had been his spirited determination and eloquence in the cause of American rights and liberties.

That he relished the sharp conflict and theater of the courtroom, that he loved the esteem that came with public life, no less than he loved “my farm, my family and goose quill,” there is no doubt, however frequently he protested to the contrary. His desire for “distinction” was too great. Patriotism burned in him like a blue flame. “I have a zeal at my heart for my country and her friends which I cannot smother or conceal,” he told Abigail, warning that it could mean privation and unhappiness for his family unless regulated by cooler judgment than his own.

In less than a year's time, as a delegate to the Continental Congress at Philadelphia, he had emerged as one of the most “sensible and forcible” figures in the whole patriot cause, the “Great and Common Cause,” his influence exceeding even that of his better-known kinsman, the ardent Boston patriot Samuel Adams.

He was a second cousin of Samuel Adams, but “possessed of another species of character,” as his Philadelphia friend Benjamin Rush would explain. “He saw the whole of a subject at a glance, and... was equally fearless of men and of the consequences of a bold assertion of his opinion.... He was a stranger to dissimulation.”

It had been John Adams, in the aftermath of Lexington and Concord, who rose in the Congress to speak of the urgent need to save the New England army facing the British at Boston and in the same speech called on Congress to put the Virginian George Washington at the head of the army. That was now six months past. The general had since established a command at Cambridge, and it was there that Adams was headed. It was his third trip in a week to Cambridge, and the beginning of a much longer undertaking by horseback. He would ride on to Philadelphia, a journey of nearly 400 miles that he had made before, though never in such punishing weather or at so perilous an hour for his country.

The man riding with him was Joseph Bass, a young shoemaker and Braintree neighbor hired temporarily as servant and traveling companion.

The day was Wednesday, January 24, 1776. The temperature, according to records kept by Adams's former professor of science at Harvard, John Winthrop, was in the low twenties. At the least, the trip would take two weeks, given the condition of the roads and Adams's reluctance to travel on the Sabbath.

* * *

To ABIGAIL ADAMS, who had never been out of Massachusetts, the province of Pennsylvania was “that far country,” unimaginably distant, and their separations, lasting months at a time, had become extremely difficult for her.

“Winter makes its approaches fast,” she had written to John in November. “I hope I shall not be obliged to spend it without my dearest friend... I have been like a nun in a cloister ever since you went away.”

He would never return to Philadelphia without her, he had vowed in a letter from his lodgings there. But they each knew better, just as each understood the importance of having Joseph Bass go with him. The young man was a tie with home, a familiar home-face. Once Adams had resettled in Philadelphia, Bass would return home with the horses, and bring also whatever could be found of the “common small” necessities impossible to obtain now, with war at the doorstep.

Could Bass bring her a bundle of pins? Abigail had requested earlier, in the bloody spring of 1775. She was entirely understanding of John's “arduous task.” Her determination that he play his part was quite as strong as his own. They were of one and the same spirit. “You cannot be, I know, nor do I wish to see you, an inactive spectator,” she wrote at her kitchen table. “We have too many high sounding words, and too few actions that correspond with them.” Unlike the delegates at Philadelphia, she and the children were confronted with the reality of war every waking hour. For though British troops were bottled up in Boston, the British fleet commanded the harbor and the sea and thus no town by the shore was safe from attack. Those Braintree families who were able to leave had already packed and moved inland, out of harm's way. Meanwhile, shortages of sugar, coffee, pepper, shoes, and ordinary pins were worse than he had any idea.

“The cry for pins is so great that what we used to buy for 7 shillings and six pence are now 20 shillings and not to be had for that.” A bundle of pins contained six thousand, she explained. These she could sell for hard money or use for barter.

There had been a rush of excitement when the British sent an expedition to seize hay and livestock on one of the islands offshore. “The alarm flew

[like]

lightning,” Abigail reported, “men from all parts came flocking down till 2,000 were collected.” The crisis had passed, but not her state of nerves, with the house so close to the road and the comings and goings of soldiers. They stopped at her door for food and slept on her kitchen floor. Pewter spoons were melted for bullets in her fireplace.

“Sometimes refugees from Boston tired and fatigued, seek an asylum for a day or night, a week,” she wrote to John. “You can hardly imagine how we live.”

“Pray don't let Bass forget my pins,” she reminded him again. “I endeavor to live in the most frugal manner possible, but I am many times distressed.”

The day of the battle of Bunker Hill, June 17, 1775, the thunder of the bombardment had been terrifying, even at the distance of Braintree. Earlier, in April, when news came of Lexington and Concord, John, who was at home at the time, had saddled his horse and gone to see for himself, riding for miles along the route of the British march, past burned-out houses and scenes of extreme distress. He knew then what war meant, what the British meant, and warned Abigail that in case of danger she and the children must “fly to the woods.” But she was as intent to see for herself as he, and with the bombardment at Bunker Hill ringing in her ears, she had taken seven-year-old Johnny by the hand and hurried up the road to the top of nearby Penn's Hill. From a granite outcropping that breached the summit like the hump of a whale, they could see the smoke of battle rising beyond Boston, ten miles up the bay.