John Aubrey: My Own Life (29 page)

Read John Aubrey: My Own Life Online

Authors: Ruth Scurr

I have drawn inspiration

15

from a short poem printed at London:

The Shepherds Delight Both by Day and by Night

, describing the shepherds’ simplicity and their felicity; their birth and their mirth; their lives and their wives; their health and their wealth; their ways and their plays; their diet and quiet. And how their damsels, they laugh and lie down, and to each pretty virgin they give a green gown. This poem was sung to a delightful tune at the Duke’s Playhouse, before the King and the nobility.

I shall set my play

16

amidst a revel on St Peter’s Day, when there is a collection for the poor. I will take one of my characters – Sir Fastidious Overween – from the Earl of Oxford’s secretary Gwyn: a better instance of a squeamish and disobliging, slighting, insolent, proud fellow cannot be found. No reason satisfies him, but he overweens, and cuts sour faces that would turn the milk in a fair lady’s breast.

. . .

If I desired to be rich, I could be a prince and go to Maryland, one of the finest countries in the world, with a climate like France. Lord Baltimore’s brother is his lieutenant there: a very good-natured gent. There is plenty of everything there; land for 2,000 miles westward. I could take a colony of rogues with me, another of ingenious artificers, and I am sure I could fix things so I took five or six companions along for ingenious conversation (which would be enough).

. . .

Mr Hobbes tells me that if he thought Magdalen Hall would accept them, he would give them his works. I will ask Mr Wood to make enquiries about this.

I have been told there is a Fellow at Merton who can conjure and quieten troubled houses. I hope Mr Wood can find out more, for I would love to be acquainted with such a person.

. . .

Before I leave England

17

on my travels, I hope to go to Oxford to see Mr Wood, but must do so incognito, like an invisible ghost, for fear of creditors. Even my letters I must collect secretly: they come addressed to my brother Thomas and care of the Lambe in Katherine Street, Sarum, or else addressed to my brother William care of his landlord in Kington St Michael.

. . .

A cabal of witches has been detected at Malmesbury. Sir James Long of Draycot Cerne, my honoured friend and an absolute gentleman, has examined them and committed them to Salisbury Gaol. I think seven or eight of these old women will be hanged. Odd things have been sworn against them: the strange manner of the dying of a local horse, and flying in the air on a staff. Sir James has written up his examinations fairly in a book that he has promised to give to the Royal Society.

Sir James and I

18

will go hawking together again soon: he is a man of exceptional charm. One time, when Oliver Cromwell was out hawking on Hounslow Heath, he got talking to Sir James and fell in love with his company, despite the fact that Sir James led the Royalist charge on Chippenham in 1644 and chased the Parliamentarian soldiers along the road towards Malmesbury. Oliver Cromwell ordered Sir James to wear his sword and meet him again for hawking, which caused the strict Cavaliers to look at him with an evil eye. When we hawk together I am reminded of what a great historian and romancer Sir James is. His History and Causes of the Civil War is a wonderful book that should be printed. I am deeply fond of Sir James’s wife Dorothy too.

. . .

Phantoms. Though I myself have never seen any such things, yet I will not conclude that there is no truth at all in reports of them. I believe that, extraordinarily, there have been such apparitions; but where one is true a hundred are figments. There is a lechery in lying and imposing on the credulous; and the imagination of fearful people tends towards admiration.

For example: not long after the Roman mosaics in the cave at Bathford (near Bath) were discovered in 1655, a ploughboy happened to fall asleep close to the mouth of the cave. A gentleman chanced to be sailing past in a boat on the River Avon, which runs close by, playing on his flajolet. The boy woke, believed the music to be coming from the cave, and ran away in lamentable fright: his fearful fancy made him believe that he saw spirits in the cave. Mr Skreen, in whose grounds the mosaics were discovered, told me that the locals believe the ploughboy and cannot be undeceived.

The mosaic, or

opus tesselatum

pavement, was made of small stones of several colours: white (hard chalk), blue (liasse) and red (fine brick). In the middle of the floor was a blue bird, not well proportioned, and in each of the four angles a sort of knot. This ground and the whole manor used to belong to the abbey of Bath. Underneath the floor there is water. The floor is supported by pillars of stone. On top of the pillars, plank stones were laid, and on top of them the mosaic. The water issued out of the earth a little below.

After the mosaic

19

was discovered, so many people came to see it, from Bath especially, that Mr Skreen had to cover it up again to halt the damage that the visitors were doing to his grounds. Unfortunately, he did not do this soon enough to stop them tearing up all the best part of the mosaic before I managed to see it. But Mr Skreen’s daughter-in-law showed me the tapestry she made, copying the whole floor with her needle in gobelin-stitch. Mr Skreen says there is another floor, adjacent to the one that has been destroyed, that is still untouched.

. . .

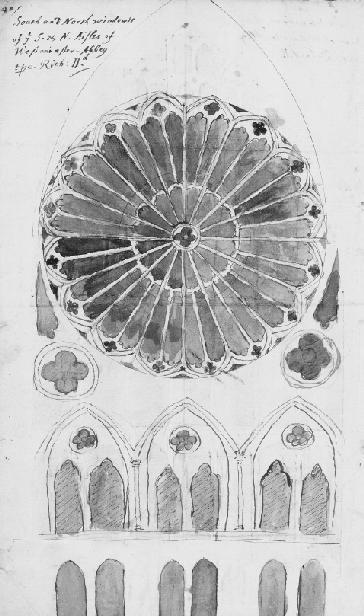

This year I have begun transcribing notes on architecture that I have been collecting for many years now. My idea is to write a Chronologia of architecture. I have become very interested in how Roman architecture degenerated into Gothic, before gradually recovering its antique purity.

I have noticed

20

that the shape of the windows is often the surest indicator of the age of a building, and I have been sketching pictures in ink of different styles of windows in important or interesting buildings. Perhaps I can gather them into a short book and dedicate it to my cousin Sir John Aubrey. I have drawn careful diagrams of the different kinds of windows in the church at Kington St Michael. I notice that the windows of the tower of Kington St Michael are of the same kind as those in the church at Ifley, near Oxford. I must ask Mr Wood to find out when the Ifley church was built.

I think it would be easy too to make a Chronologia of styles of handwriting from the Norman Conquest to the present day: which would be very useful to have.

I have sought advice

21

on collecting statistics from Sir William Petty and he has sent me some helpful directions.

. . .

December

Two trunks full

22

of my books, which I left with Mr Fabian Stedman, have been seized by his landlady for debts. I hope I can recover them.

. . .

I wish to go

23

to Oxford, but am fearful of the fever, so common and infectious. I have written to Mr Wood to ask if he believes there is any danger, or might I risk a visit soon?

. . .

I have been sending

24

Mr Wood many notes for his great book on the history and antiquities of Oxford University, including some information about Dr Thomas Muffet, of Trinity College, Cambridge, and Gonville Hall, the author of

De Insectis

, who lived and died at Wilton House and was physician to Mary, Countess of Pembroke, Sir Philip Sidney’s sister. Quaere: Dr John Pell told me that

De Insectis

was begun by a friar. In about 1649, long after Dr Muffet’s death, his book

Of Meates

was printed. I have it and must check the date of printing. I also have the Life of Sir Philip Sidney, written by Sir Fulke Greville.

. . .

Anno 1672

January

Mr Edward Bradsaw

25

, my old acquaintance from the Middle Temple, a religious controversialist, was buried on the first day of this month, in the burying place for fanatics by the artillery ground in Moorfields. There were between 1,500 and 2,000 at his funeral. He died on 28 December in Tuttle Street, Westminster. He was forty-two years old and on parole from Newgate Prison, where he was serving a sentence of twenty-two weeks for refusing to take the Oath of Allegiance. I will go to visit his sorrowful widow as soon as I can. She intends to place an epitaph for him.

. . .

My lord the Earl

26

of Thanet has thanked me for my thoughts on how lanterns might be better fixed to coaches. I have the idea that the lantern could be fixed to the end of the pole between the shafts, closer to the ground, but he argues that this will not work as the horses may break it, or it will be thrown against them on rugged ways. He insists the lantern must go on the top of the coach above the coachman’s head. He invites me to visit him in Hothfield and to make an inventory for him of all his land: the name, situation and boundary of every field. I could travel there by water and take a horse from Gravesend for the last part of the journey.

. . .

11 January

Mr Isaac Newton

27

has been elected Fellow of the Royal Society.

. . .

To help Mr Wood

28

, I have searched through the records of the Heralds’ Office from 1617 to 1642. The archive has been rehoused since the Great Conflagration.

. . .

February

Sir John Hoskyns

29

has written to me of phantoms – a fundamental of the Tridentine creed: the sudden ataxies of the spirits that forerun death – and stories of dreams predicting events. He tells of magic and ominous appearances of lights in rooms and of ancient superstition. He says the plant woad is a cure for cancer of the breast; and that he has seen crystal spheres for sale.

. . .

March

I am going to Somerset

30

tomorrow, to see my mother, now living at Bridgwater, and a cousin at Wells. About half a mile from Bridgwater is a place called Chief Chidley Mount, which was inhabited by the Romans and where Roman coins have been found. Bridgwater sprang out of the Roman ruins.

. . .

Mr John Evelyn has become secretary of the Royal Society.

. . .

6 April

On this day, England joined France in declaring war on the Dutch Republic. The Parliament has little enthusiasm for this new war.

. . .

Mr Paschall has written to thank me for my persevering zeal in the search for a philosophic language. He intends to send me more questions about the ‘Universal Character’.

. . .

The headmaster of Brentwood

31

School modelled his teaching method on the Comenius didactic, after Mr Paschall recommended it, and having done so, made that great educational foundation both famous and useful. Mr Paschall hopes to prevail on the new headmaster of Bridgwater School to adopt the same method (which involves substituting emulation and shame for the rod: inducements to learning, instead of punishments) and wishes the headmaster of Brentwood School would publish an account of his experience and success as an educator: he is an ingenious man. How much better my own schooling at Blandford would have been if the masters there had followed Comenius’s methods.

I know of men

32

aged forty or more who, whenever anything troubles them, dream they are back under the tyranny of their schoolmaster, so strong an impression does the horror of discipline leave.

. . .

May

I have been to Oxford to see Mr Wood, whom I have been longing to see. And now I will go to Essex, Norfolk, Cambridge, and finally to London: all in about ten days.

For his collection

33

of short biographies of the writers and bishops who have attended Oxford University, Mr Wood’s method is to find answers to these questions:

Where was . . . born?

What employment or preferment had he?

What did he write?

When and where was his death and burial?

What, if any, was his epitaph?

I am doing my best to help him collect answers to these questions whenever possible.

Mr Wood is a candid historian

34

who does not make himself a judge of men’s merits or abilities, but instead takes great pains to record all his subjects’ printed writings and unpublished manuscripts. I commend his minuteness, but would like to go even further toward recording the tiny details that shape lives.

. . .

My honoured friend

35

, Samuel Cooper, His Majesty’s limner, has died after a sudden illness at the age of sixty-three. He is now buried in the chancel of St Pancras Church in the next grave to Father Symonds, the Jesuit. Their coffins touch.