Read Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Online

Authors: Jules Verne

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) (23 page)

BOOK: Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

6.6Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

It was a real ocean, with the irregular outline of earthly shores, but deserted and frighteningly wild.

If my eyes were able to range widely over this great sea, it was because a special “light” illuminated its most minor details. It was not the light of the sun, with its shafts of brightness and the splendid radiation of its beams, nor was it the pale and uncertain gleam of the night star, which is only a reflection without heat. No. The illuminating power of this light, its trembling diffusiveness, its clear, dry whiteness, its low temperature and its brightness which surpassed that of the moon showed that it must obviously be of electric origin. It was like an aurora borealis, a constant cosmic phenomenon that filled a cavern large enough to contain an ocean.

The vault suspended above my head, the sky, so to speak, seemed made up of vast clouds, shifting and moving steam, which through condensation had to turn into torrential rain on certain days. I would have thought that under such high atmospheric pressure, there could be no evaporation; and yet, for a physical reason that eluded me, large clouds of steam extended in the air. But at that time ‘the weather was good.’ The electric layers produced astonishing effects of light on the highest clouds. Deep shadows were sketched on their lower wreaths, and often, between two separate layers, a beam pierced through to us with remarkable intensity. But overall it was not the sun because its light had no heat. Its effect was sad, supremely melancholy. Instead of a firmament glittering with stars, I sensed a granite vault above these clouds that crushed me with all its weight, and all this space, enormous it was, would not have been enough for the movement of the humblest satellite.

Then I remembered the theory of an English captain, who likened the earth to a vast hollow sphere,

ay

inside of which the air remained luminous because of the immense pressure, while its two stars, Pluto and Proserpine,

az

followed their mysterious orbits there. Could he have been right?

ay

inside of which the air remained luminous because of the immense pressure, while its two stars, Pluto and Proserpine,

az

followed their mysterious orbits there. Could he have been right?

We were in reality imprisoned inside an immense cavity. Its width was impossible to judge, since the shore ran as far as the eye could reach, and so was its length, for the eye soon came to a halt at a somewhat indistinct horizon. As for its height, it must have exceeded several leagues. Where this vault rested on its granite base no eye could tell; but there was a cloud suspended in the atmosphere whose height we estimated at two thousand fathoms, a greater height than that of any terrestrial steam, due no doubt to the considerable density of the air.

The word “cavern” obviously does not convey any idea of this immense space; but the words of the human language are inadequate for one who ventures into the abyss of earth.

I did not know, at any rate, what geological fact would explain the existence of such a cavity. Had the cooling of the globe been able to produce it? I knew of certain famous caverns from the descriptions of travelers, but had never heard of any with such dimensions.

Even if the grotto of Guachara in Colombia, visited by Humboldt,

ba

had not yielded the secret of its depth to the scholar who explored 2,500 feet of it, it probably did not extend much farther. The immense mammoth cave in Kentucky is of gigantic proportions, since its vaulted roof rises five hundred feet above an unfathomable lake, and travelers have explored more than ten leagues without finding the end. But what were these cavities compared to the one which I was now admiring, with its sky of steam, its electric radiation, and its vast enclosed ocean? My imagination felt powerless before such immensity.

ba

had not yielded the secret of its depth to the scholar who explored 2,500 feet of it, it probably did not extend much farther. The immense mammoth cave in Kentucky is of gigantic proportions, since its vaulted roof rises five hundred feet above an unfathomable lake, and travelers have explored more than ten leagues without finding the end. But what were these cavities compared to the one which I was now admiring, with its sky of steam, its electric radiation, and its vast enclosed ocean? My imagination felt powerless before such immensity.

I gazed on all these wonders in silence. Words failed me to express my feelings. I felt as if I were witnessing phenomena on some distant planet, Uranus or Neptune, of which my “terrestrial” nature had no knowledge. For such novel sensations, new words were needed, and my imagination failed to supply them. I gazed, I thought, I admired with amazement mingled with a certain amount of fear.

The unforeseen nature of this spectacle brought healthy color back to my cheeks. I treated myself with astonishment, and was effecting a cure with this new therapy; besides, the keenness of the very dense air reinvigorated me, supplying more oxygen to my lungs.

It will be easy to understand that after an imprisonment of forty-seven days in a narrow tunnel, it was an infinite pleasure to breathe this air full of moisture and salt.

So I had no reason to regret that I had left my dark grotto. My uncle, already used to these wonders, was no longer astonished.

“You feel strong enough to walk a little?” he asked me.

“Yes, certainly,” I answered, “and nothing could be more pleasant.”

“Well, take my arm, Axel, and let’s follow the meanderings of the shore.”

I eagerly accepted, and we began to walk along the edge of this new ocean. On the left steep cliffs, piled on top of one another, formed a titanic heap with a prodigious appearance. Down their sides flowed innumerable waterfalls, which turned into limpid, resounding streams. A few bits of steam, leaping from rock to rock, marked the location of hot springs, and streams flowed gently toward the shared basin, taking the slopes as an opportunity to murmur even more pleasantly.

Among these streams I recognized our faithful traveling companion, the Hansbach, which came to lose itself quietly in the ocean, just as if it had done nothing else since the beginning of the world.

“We’ll miss it,” I said, with a sigh.

“Bah!” replied the professor, “this one or another one, what does it matter?”

I found this remark rather ungrateful.

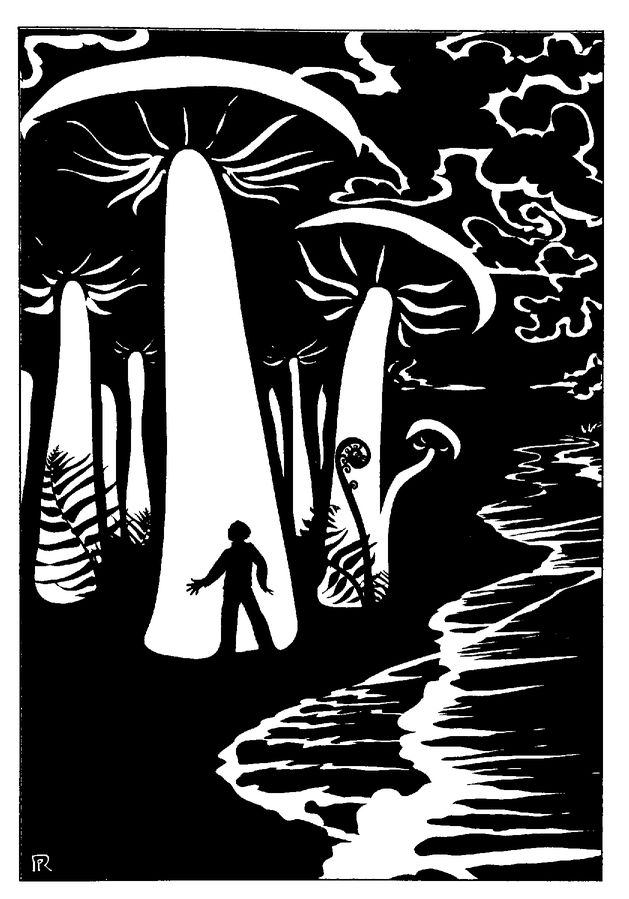

But at that moment my attention was attracted to an unexpected spectacle. At a distance of five hundred feet, at the turn of a high promontory, a high, tufted, dense forest appeared before our eyes. It consisted of moderately tall trees shaped like normal parasols, with precise geometrical outlines. The currents of wind seemed to have no impact on their leaves, and in the midst of the breezes they stood unswerving like a clump of petrified cedars.

I hastened forward. I could not give a name to these peculiar specimens. Did they not form part of the two hundred thousand plant species known to date, and was it necessary to give them a place of their own among the water plants? No. When we arrived in their shade my surprise turned into admiration.

In fact, I was facing products of the earth, but grown to gigantic stature. My uncle immediately called them by their name.

“It’s just a forest of mushrooms,” he said.

And he was right. Imagine the development of these plants, which prefer a warm, moist climate. I knew that according to Bulliard,

bb

the Lycoperdon

giganteum

reaches a circumference of eight or nine feet; but these were white mushrooms thirty to forty feet tall, with a cap of the same diameter. There they stood by the thousands. No light could penetrate into their shade, and complete darkness reigned beneath these juxtaposed domes that resembled the round, thatched roofs of an African town.

bb

the Lycoperdon

giganteum

reaches a circumference of eight or nine feet; but these were white mushrooms thirty to forty feet tall, with a cap of the same diameter. There they stood by the thousands. No light could penetrate into their shade, and complete darkness reigned beneath these juxtaposed domes that resembled the round, thatched roofs of an African town.

Yet I wanted to go further. A deadly cold descended from these fleshy vaults. For half an hour we wandered in the humid darkness, and it was with a genuine feeling of well-being that I returned to the seashore.

But the vegetation of this subterranean region was not limited to mushrooms. Farther on there were clusters of tall trees with faded foliage. They were easy to identify; these were the lowly shrubs of earth in prodigious sizes, lycopods a hundred feet tall, giant sigillarias, tree ferns as tall as pines in northern latitudes, lepidodendra with cylindrical forked stems ending in long leaves and bristling with coarse hairs like monstrous fat plants.

“Amazing, magnificent, splendid!” exclaimed my uncle. “Here is the entire flora of the Secondary period of the world, the Transition period. Look at these humble garden plants that were trees in the early ages of the globe! Look, Axel, and admire them! Never has a botanist been at a celebration such as this!”

“You’re right, Uncle. In this immense greenhouse, Providence seems to have wanted to preserve the prehistoric plants which the wisdom of scholars has so successfully reconstructed.”

“You put it well, my boy, it is a greenhouse; but you’d put it even better if you added that it’s perhaps a zoo.”

“A zoo.”

“Yes, no doubt. Look at this dust under our feet, these bones scattered on the ground.”

“Bones!” I exclaimed. “Yes, bones of prehistoric animals!”

I rushed toward these centuries-old remains made of an indestructible mineral substance.

bc

Without hesitation I could name these gigantic bones that resembled dried-up trunks of trees.

bc

Without hesitation I could name these gigantic bones that resembled dried-up trunks of trees.

“Here is the lower jaw of a mastodon,” I said. “These are the molar teeth of the deinotherium; this femur must have belonged to the greatest of those beasts, the megatherium.

bd

It certainly is a zoo, for these remains were not brought here by a cataclysm. The animals to whom they belonged lived on the shores of this subterranean sea, under the shade of those tree-sized plants. Look, I see entire skeletons. And yet...”

bd

It certainly is a zoo, for these remains were not brought here by a cataclysm. The animals to whom they belonged lived on the shores of this subterranean sea, under the shade of those tree-sized plants. Look, I see entire skeletons. And yet...”

“And yet?” said my uncle.

“I don’t understand the presence of such quadrupeds in this granite cavern.”

“Why?”

“Because animal life existed on the earth only in the Secondary period, when a sedimentary soil had been created through alluvial deposits and had taken the place of the white-hot rocks of the Primitive period.”

“Well, Axel, there’s a very simple answer to your objection, and that is that this soil is alluvial.”

“What! at such a depth below the surface of the earth?”

“No doubt; and there’s a geological explanation for this fact. At a certain period the earth consisted only of a flexible crust, subject to alternating movements from above or below, by virtue of the laws of gravity. Probably there were landslides, and some alluvial soil was precipitated to the bottom of these chasms that had suddenly opened up.”

“That must be it. But if prehistoric animals have lived in these underground regions, who says that one of these monsters is not still roaming in these gloomy forests or behind these steep crags?”

At this thought, I surveyed the various directions not without fear; but no living creature appeared on the barren strand.

I felt rather tired, and went to sit down at the end of a promontory, at whose foot the waves broke noisily. From here my view included this entire bay formed by an indentation of the coast. In the background, a little harbor lay between pyramidal cliffs. Its still water rested untouched by the wind. A brig and two or three schooners could easily have cast anchor in it. I almost expected to see some ship leave it with sails set and take to the open sea under the southern breeze.

But this illusion vanished quickly. We were the only living creatures in this subterranean world. When there was a lull in the wind, a silence deeper than that of the desert fell on the arid rocks and weighed down on the surface of the ocean. I then tried to pierce the distant haze and to tear the curtain that hung across the mysterious horizon. What questions lay at the tip of my tongue? Where did that ocean end? Where did it lead to? Could we ever explore its opposite shores?

These were white mushrooms thirty to forty feet tall.

My uncle had no doubt about it. I both desired and feared it at the same time.

After spending an hour in the contemplation of this marvelous spectacle, we walked back on the pebbles to the grotto, and I fell into a deep sleep in the midst of the strangest thoughts.

XXXI

THE NEXT MORNING I woke up feeling perfectly well. I thought a bath would do me good, and I went to dive into the waters of this Mediterranean sea for a few minutes. Certainly it deserved this name more than any other ocean.

be

be

I came back to breakfast with a good appetite. Hans knew how to cook our little meal; he had water and fire at his disposal, so that he could change our ordinary fare a bit. For dessert he served us a few cups of coffee, and this delicious beverage never seemed more pleasant to my sense of taste.

“Now,” said my uncle, “this is the time of the high tide, and we mustn’t miss the opportunity to study this phenomenon.”

“What, the tide!” I exclaimed.

“No doubt.”

“Can the influence of the sun and moon be felt even here?”

“Why not? Aren’t all bodies subject to universal gravity in their entirety? So this mass of water can’t escape the general law. And in spite of the heavy atmospheric pressure on the surface, you’ll see it rise like the Atlantic itself.”

At that moment we walked on the sand of the shore, and the waves were gradually encroaching on the pebbles.

“Here’s the beginning of high tide,” I exclaimed.

“Yes, Axel, and judging from these tidemarks of foam, you can see that the ocean rises about ten feet.”

“That’s wonderful!”

BOOK: Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

6.6Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

Crazy For You by Jennifer Crusie

A Soldier's Heart by Alexis Morgan

Hungry Independents (Book 2) by Ted Hill

First Offense by Nancy Taylor Rosenberg

Leading Lady by Leigh Ellwood

Consumed by Shaw, Matt

The Protected (Fbi Psychics) by Walker, Shiloh

Murder in Piccadilly by Charles Kingston

Mummy Told Me Not to Tell by Cathy Glass

Mama Gets Trashed (A Mace Bauer Mystery) by Sharp, Deborah