Kabbalah (5 page)

These concepts no longer seem valid. Recent scholarly work on ancient Gnosticism—including that of Michael Williams, Karen King, and Elaine Pagels—denies the existence of such a “third religion.” These scholars describe the sects so designated as an expression of the variety and complexity of early Christianity, and reject the anachronistic castigation of “heresy” when discussing them. It seems today that the image of Gnosticism that was prominent in the mid-twentieth century is more an 23

K A B B A L A H

expression of the prejudices and speculations of modern scholars than a reflection of historical reality. The Nag Hamadi library includes treatises concerning many directions and emphases of Christian thought in the early centuries, rather than the expression of one religious worldview. No historical connection has been demonstrated between the ancient gnostic sects and medieval spiritual movements.

A negative can never be proven, yet after a century and a half of searching for Jewish Gnosticism it has to be stated that no evidence of the existence of such a phenomenon has been found. The only basis for speculation in this direction has been the existence of a gnostic religion in the Christian context in ancient times and the Middle Ages; when doubts are cast concerning the existence of pre-Christian and Christian Gnosticism, there is no reason to use this term concerning Jewish phenomena. The assumption that the Book Bahir was influenced either by ancient Jewish gnostic traditions or by Christian Gnosticism, ancient or medieval (that is, Catharic), has not been proven by any textual or terminological evidence. As far as we know today, the mythical concepts that make the Book Bahir a new, radical phenomenon in Jewish spirituality were originated by the author of that book. If so, the kabbalah has to be seen as an innovative Jewish spiritual phenomenon originating in the High Middle Ages. Some of its ideas may be similar to those of other groups within Judaism or outside of it, but no historical connection to other schools has been discovered so far.

24

T H E K A B B A L A H I N T H E M I D D L E A G E S

3

The Kabbalah

in the Middle Ages

The first kabbalistic text with a known author that reached us is a brief treatise, a commentary on the Sefer Yezira written by Rabbi Isaac ben Abraham the Blind, in Provence near the turn of the thirteenth century. Rabbi Isaac was the son of a great halakhist, Rabbi Abraham of Posquierre, who wrote the first critique of Maimonides’s Code of Law. Rabbi Isaac was the teacher and central figure in a small group of kabbalists in Provence, and his teachings were frequently quoted by kabbalists in the next generations. The Provence school developed the concept of the ten

sefirot

in a profound manner, yet they used a terminology that is meaningfully different from that of the Book Bahir. Their worldview was very close to that which is presented in the Book Bahir, but the differences between them prevent us from determining whether they knew the text of the Bahir or whether they developed their system independently. They were familiar with the terminology of Jewish philosophical rationalism of that time, yet they used these concepts in a unique manner, as representing realms and processes within the Godhead.

Rabbi Isaac the Blind was accepted as guide and teacher by a group of kabbalists that was established in the small Catalonian town of Girona, near Barcelona, in the first half of the thirteenth century. The dominant figure in this group was Rabbi 25

K A B B A L A H

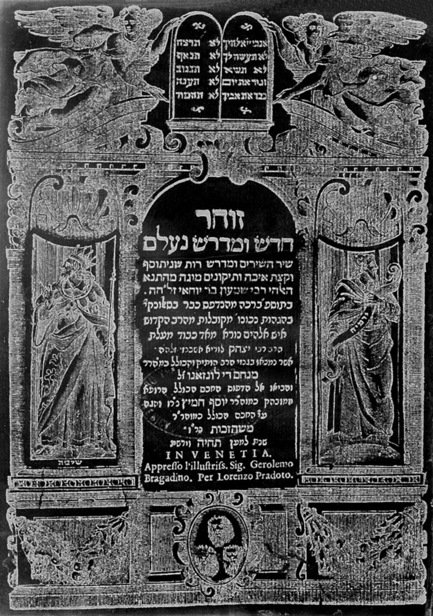

3 After much speculation, today it is widely agreed that the greatest work of the medieval kabbalah, the book Zohar, the Book of Splendor, was written mainly by Rabbi Moshe de Leon in the late 13th century.

26

T H E K A B B A L A H I N T H E M I D D L E A G E S

Moses ben Nachman (known as Nachmanides), who was regarded as the leader of the Jews in northern Spain. He was a great halakhist and preacher, and represented Judaism in polemical confrontations with Christian theologians. His main work is a commentary on the Pentateuch, in which he sometimes hinted at the kabbalistic stratum of the meaning to the scriptures. The founders of the Girona school were Rabbi Ezra and Rabbi Azriel, who wrote kabbalistic treatises and commentaries on biblical and talmudic texts. In this circle, the teachings of the Book Bahir and those of the Provence kabbalists were united into a coherent system, which served as the basis of medieval kabbalah as a whole. Some writers from this group participated in the great controversy concerning the philosophy of Maimonides, which erupted in 1232 and continued for three generations. Some historians of Jewish medieval culture described the kabbalah as a spiritual reaction to Jewish rationalism, presenting a more experiential religiosity against the “cold, distant” conceptions of the rationalists. The Girona kabbalists were versed in the teachings of Jewish philosophy, but they integrated them, like the Provence kabbalists, within their nonrationalistic system. The great contribution of the Girona writers to the history of the kabbalah was their presentation of the ancient religious texts, the Bible and the Talmud, as including a hidden kabbalistic stratum of meaning, that can be understood only by scholars versed in the secrets of the kabbalistic tradition. They tended not to reveal these secrets in their popular works, and wrote several traditional treatises on ethics (especially on repentance), in which they presented themselves as following talmudic teachings without presenting their underlying kabbalistic worldview.

In the second half of the thirteenth century, several kabbalistic circles were active in Spain. Among them were those of the brothers Rabbi Jacob and Rabbi Isaac, sons of Rabbi Jacob ha-Cohen of Castile and that of the lonely mystic wanderer

,

Rabbi Abraham Abulafia, who developed a different direction of kabbalistic speculation. Abulafia’s numerous treatises have 27

K A B B A L A H

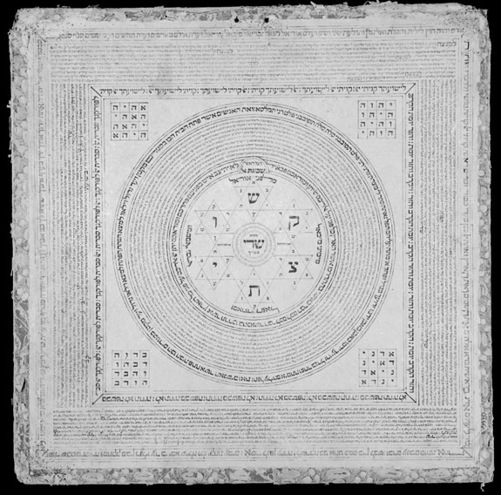

4 Permutations of divine names and names of angels in a protective amulet.

28

T H E K A B B A L A H I N T H E M I D D L E A G E S

been described by Scholem as “ecstatic” or “prophetic” kabbalah, which emphasized the visionary and experiential aspect, and relied on novel approaches to the Hebrew alphabet and the numbers as the source of divine truths. Abulafia’s teachings represented the mystical tendencies among kabbalists, instead of the theosophical and traditional speculations that prevailed in other circles.

One of his disciples was Rabbi Joseph Gikatilla, who later changed his mind and joined the school of Rabbi Moses de Leon, the author of the Zohar. Gikatilla wrote one of the most influential presentations of the kabbalistic worldview,

Shaaey

Ora

(The Gates of Light), a summary of the teachings of the kabbalah arranged according to the order of the ten

sefirot

.

Another circle of kabbalists assembled around Rabbi Shlomo ben Adrat, known by the acronym RaSHBAh, a great halakhist and leader at the end of the thirteenth and the beginning of the fourteenth centuries. This period can be regarded as the peak of the creativity and influence of the medieval kabbalah, which began to spread to Italy, Germany, and the east, and became a meaningful, though still esoteric and marginal, component of Jewish religious culture. The most important circle was that which assembled around Rabbi Moses de Leon in northern Spain, the circle that produced the greatest work of the medieval kabbalah, the book Zohar.

The belief in the book Zohar as a traditional work standing beside the Bible and the Talmud as the three pillars of Jewish faith and ancient tradition has become an article of faith in modern orthodox Judaism. Confidence that the Zohar was actually written by the sage Rabbi Shimeon bar Yohai in the early second century CE defines a Jew as completely orthodox, and doubting this is regarded as the beginning of heresy and denial of Jewish tradition. It became an article of faith for the Christian kabbalah as well. The fact is that since the end of the fifteenth 29

K A B B A L A H

century there were Jewish thinkers who doubted this attribu-tion and stated that the work is a medieval one, written by Rabbi Moses de Leon, who died in 1305. Rabbi Judah Arieh of Modena presented a detailed, systematic argument to that effect in the middle in the seventeenth century. Among modern scholars there were some who were hesitant, but Heinrich Graetz, the great nineteenth-century historian, accepted and developed Modena’s argument and Gershom Scholem presented a detailed justification for the medieval origin in his

Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism

(1941). Scholem’s closest disciple, Isaiah Tishby, further developed this line of reasoning in his

Wisdom of the

Zohar

(Hebrew, 1949; English, 1989) and several other studies.

Today, while there is still some debate concerning the exact date of the Zohar’s composition and concerning the participation of some other kabbalists in the writing of the work, there seems to be no doubt that the Zohar was written mainly by Rabbi Moses de Leon in the last decades of the thirteenth century.

De Leon, who wrote several kabbalistic works other than the Zohar, used to sell portions of the Zohar to people interested in esoteric traditions, claiming that he was copying it from an ancient manuscript that reached him from the Holy Land.

We have an incomplete document written by a kabbalist a short time after de Leon’s death, in which a story is told about the authorship of the Zohar. According to it, de Leon left his widow and daughter destitute when he died. A rich kabbalist offered them a large sum of money if they would sell him the original manuscript from which de Leon claimed to have copied the various portions of the Zohar. The widow said that she was unable to do that, because her late husband “wrote from his own mind” and there was no source from which he was copying. Scholars have made different interpretations of this document, and clearly it cannot alone serve as proof. Yet, integrated with numerous philological and linguistic characteristics, it seems that De Leon was the principal author of the main part of the Zohar.The Zohar is actually a library, comprised of more than a score of treatises. The main part, the body of the Zohar, 30

T H E K A B B A L A H I N T H E M I D D L E A G E S

is a homiletical commentary in Aramaic on all the portions of the five books of the Pentateuch, as if they were ancient midrashic works (though they were not, as a rule, written in Aramaic). Among the other treatises included in the body of the Zohar are: the Midrash ha-Neelam (The Esoteric Midrash), written partly in Hebrew, and probably the first part of this huge work to be written; a section dedicated to the discussion of the commandments; and others including revelations by a wondrous old man (

sava

) and a boy (

yenuka

). The most esoteric discussions, regarded as the holiest part of the Zohar, are called Idra Rabba (The Large Assembly) and Idra Zuta (The Small Assembly). A later writer imitating the style and language of de Leon added two works to the Zohar in the beginning of the fourteenth century: Raaya Mehemna (The Faithful Shepherd, meaning Moses), which is presented in several sections of the work, and Tikuney Zohar (Emendations of the Zohar), which was printed as an independent work. A fifth volume in the Zohar library is the Zohar Hadash (The New Zohar), a collection of material from manuscripts that were not included in the first edition of the Zohar. The body of the Zohar was first printed in Mantua in 1558–1560 in three volumes, and this is the traditional edition that was printed many times since. Another edition was published in Cremona, Italy, in 1559 in one large volume. Rav Yehuda Ashlag published a translation of the whole Zohar into Hebrew with a comprehensive traditional commentary in many volumes in the middle of the twentieth century.

The English reader can profit from the large anthology of Zohar sections in Tishby’s

Wisdom of the Zohar

and Daniel Matt’s translation and commentary (first two volumes, 2004).