Kasher In The Rye: The True Tale of a White Boy from Oakland Who Became a Drug Addict, Criminal, Mental Patient, and Then Turned 16 (29 page)

Authors: Moshe Kasher

“That’s When Ya Lost”

—

Souls of Mischief

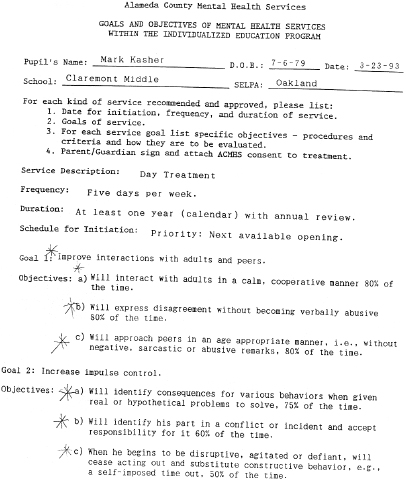

School was starting again and I was now entering my third year without having successfully passed a grade since the seventh. I was on my way to becoming the cool, older senior with a beard and a Camaro. Every time I’d get thrown back into a school, my new, doomed-to-failure educational plan would be outlined in an IEP.

An IEP, or Individualized Education Program, is created at a meeting that the school administration calls in order to determine the best means of making you successful in school. It never works. At least it never did for me.

“Well, I see here that you have been experiencing repeated failures in all of the placements we have sent you to,” the lady assigned to my case said as she handed me a chart that essentially, graphically, explained why I was such a fuckup.

“He just hasn’t found the right placement yet. That’s your

responsibility to find.” My mother scolded the school district constantly for what she perceived as their complicit involvement in my educational failures. It was never just that I’d fucked up, it was always that I hadn’t been helped right.

Codependent or not, my mother knew the system and wasn’t shy about milking it dry.

“Mrs. Kasher, the school board has done all it can do.”

My mother upended her purse to reveal the catalogs of fifteen private behavioral modification and special education schools that Oakland contracted through.

“You haven’t done enough,” she signed.

The entire team assembled by Oakland Public Schools shot eye

daggers at my mother. You could almost hear the thoughts of “that uppity deaf bitch” ringing through the room.

My mama.

Whatever, I wasn’t thrilled either. Why my mother couldn’t just let me be a high school dropout bum in peace was beyond me.

By the way, dropping out wasn’t just my idea. Oakland’s dropout rate currently sits at 40 percent (Piedmont’s is 0.09 percent).

Sorry, I didn’t mean to make this a social critique! Back to the destruction!

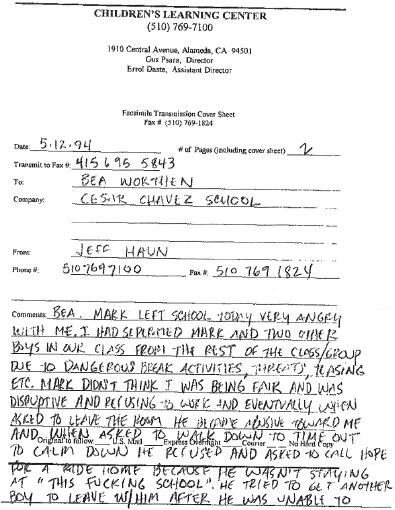

I was sent, with my mother’s blessing, to a school in Alameda called Children’s Learning Center. An innocent-enough-sounding name for a school. Well, actually perhaps an innocent name was appropriate as the student body was made up of the most innocent people in the world, the mentally retarded.

I’m not making a joke here. I mean that, literally, the entire student body at CLC, with one notable, adorable, Jewish exception, was straight up retarded.

Some severely so. Autistic children who’d severed their connections to the world in the womb, taking the shortcut on realizing that people disappoint you and retreating inside their own complicated heads where Burger King logos and numerical patterns were

very, very

important.

Some were just mildly retarded, thick-lipped and amiable with enough smarts to make you wonder, “Is he or isn’t he?” and then you’d see them picking their nose in front of a cute girl and you’d think, “Ahhh! Of course!”

I was now enrolled in a school with a student body of less than one hundred who all had IQs of less than one hundred.

There are some times when the illusion that you haven’t made

any wrong turns in life and that you are a victim of circumstance becomes very difficult to believe. Nothing quite defines that feeling as strongly as looking around a classroom and seeing drool dangling from the lip of more than one classmate surrounding you. Being the only non-retarded kid in class, at a certain point you have to ask yourself, “Am I certain I am not retarded?”

I was too weary to ask. I just showed up and did the entire battery of their hardest schoolwork in less than an hour. I’d spend the rest of the afternoon with my Walkman headphones on, feet up on the desk, a pinch of snuff in my lip spitting into a Snapple bottle in defiance. Finally the principal of the school approached me and asked if I’d like to use my sign language skills in the afternoons by helping the autistic preschoolers. I agreed to do it. I still wonder why, in the midst of all that assholery, I would have cared a bit about helping some autistic kids. I must’ve had something in me that still wanted to be good, to be okay. Also I was fascinated by them. I’d walk downstairs and work with these kids, checked out from reality, and look at them with a kind of envy. There was agony in their existence, no doubt. They would cry and scream in glass-breaking shrieks if even the slightest anomaly blipped outside of their absurdly chosen comfort zones; if snack time didn’t have animal crackers, if there was purple Play-Doh and not yellow, it became a fucking crisis. But something about the lack of concern with the real world surrounding them made me jealous. If only I could check out like that. I felt useful down there, the severity of disability at Children’s Learning Center ironically providing me an opportunity to actually feel engaged in a school setting. I felt like I was doing something good. The problem seemed to always be that I could never do good for too long.

One day, in the middle of class, I simply got up and walked out. I’d had enough. All this goody two-shoes stuff wasn’t for me. I needed to get the fuck out. Thus marked my re-entry into the high school dropout community. I was now three high schools down and no grades successfully passed. This wasn’t going well.

That night I got invited to a kegger at Lake Temescal. Temescal is a lake just up the hill from Rockridge. Far enough from the city to escape the cops’ eyes. Close enough to walk if you had to. How I ended up there I don’t really know. I was drunk, already having spent the afternoon soaking my high school dropout memories in gin.

I stumbled out onto the field at Temescal, looking for something to do. I found it. A girl I knew from the neighborhood called me over to introduce me to the guy who was hosting this outdoor soiree.

I didn’t know this guy and wondered what hell he was doing in my neighborhood, having a party.

It wasn’t that it was forbidden, it just wasn’t really done. People in Oakland didn’t try to own blocks like the gangbangers in L.A. Those guys claimed absolute ownership of neighborhoods, and they’d defend to the death any trespass. We didn’t get down like that. It was just, if you blew into the neighborhood, you made yourself a target for the hungry eyes of a group of kids so desperate for cash and drugs that they were robbing each other. And those guys were

friends

. It was

always

preferable to rob a stranger over a friend. That’s the kind of questionable closeness the relationships in Oakland yielded.

The party was nice enough. Too bad there was a dirty mole in the mix. Me. I sat down with the birthday boy and chatted him up a bit. Nice kid, a hippie from the hills, he busted out a big brown paper bag and pulled out a handful of buds.

I’m sorry, but you pull out a gallon-sized bag of weed in front of a stranger wearing a Fila hat and you should expect to get jacked.

He kept talking but I stopped listening—that bag was all I had my eyes on.

A big fat brown bag of weed. That would look so nice on my mantel. Or in my lungs. Or converted to cash that sat, plump in my pockets.

Mmmm.

I looked around. There were hippies everywhere. People I could only assume were deadlock connected to Weed-Bag Man. If I tried anything, they would pray to their Avatar Gods, trap me in a Maypole circle, and kill me with kindness.

That bag, though.

It was whispering to me, calling my name. Like a valentine, it said, “Be Mine.”

I couldn’t take it anymore. I jumped up, muttered something about being right back, and rode my bike, as fast and hard as I could, to Joey’s house about a mile away. Donny was gone and I needed help. Tough, Sean The Bomb type help.

I charged into his backyard, back by where his room was, and banged on the window. The blinds opened into a peephole and Joey’s angry eye peered through.

“Dude, what the fuck are you doing here!” Joey slid open the door and grabbed me by my shirt.

“Stop! I’m telling you! I’ve got something for us. An opportunity to split like a pound of weed.”

Now, let’s be fair here. I had no idea how much weed was in that bag. It might have been a poor man’s Russian doll of bags until he got to the little teeny bag in the middle that contained weed.

But I took a gamble. Too big of a gamble, actually.

“A pound?” Joey’s rage was ebbing, being replaced by his entrepreneurial spirit.

“Maybe more!” I said, digging my grave deeper.

“Maybe more, huh?” I knew, at this point, Joey was in. Unfortunately,

I didn’t know that Joey owed hundreds of dollars to Fat Pete for all the coke he’d been snorting lately.

Fat Pete was a thug of gigantic proportions. He was huge. Both in the gut and in the game.

Fat Pete was white, but so dedicated to the wannabe black lifestyle that he had started to actually look ethnically ambiguous. His skin may have been white, but his soul was mulatto.

Pete was the guy who had recruited Terry Candle into his empire of crime and black accents. I feared Fat Pete the way Iraqis feared Saddam Hussein. A leader, but a terrifying one.

Looking back, I realize that Pete was a petty drug dealer, a small-time coke peddler with serious drug and deep-fried food problems. At the time, though, he seemed like the closest thing to Pablo Escobar I could ever hope to meet. A legend of extreme proportions.

Apparently, Joey owed him six hundred bucks’ worth of coke that was meant to have been sold but was sniffed into Joey’s nostrils instead.

Unbeknownst to me, pounds of theoretical hippie weed was exactly what the doctor ordered to pay off this debt.

Before I had time to protest, Joey was on the phone with Fat Pete making him an offer he couldn’t refuse. A bucket of KFC. Just kidding.

“Dude, why’d you tell fucking Pete about it? That was our lick, man!” I was pissed. This shit had nothing to do with Pete, but I could envision my pounds of weed transmogrifying into a snack for him. I imagined him deep-frying the buds and sucking them into his cheeks, cackling as he dangled them just above his mouth, licking his lips like a fat cat holding a proletariat mouse by the tail in a pro-communist propaganda poster.

“Bitch, I told Pete because I fucking wanted to tell Pete. You got something to say about it?”

Joey flinched at me like he was going to punch me in the face but then went too far and, in fact, actually punched me in the face.

“Oh, sorry, dude. I meant to almost punch you, not to punch you.”

“Dude, what the fuck? Quit being such a dick!” I held the side of my face, screaming.

“Who the fuck you calling a dick?” Joey reached back and punched me in the other side of the face. This time deliberately.

To this day I have never again been punched by accident, apologized to, and then immediately punched on purpose.

I swallowed my pride and held in my tears. There was business to attend to.

We set out in Joey’s bucket, a ’92 Toyota Celica jalopy with a modified exhaust that screamed when he accelerated. I didn’t even know what we were doing anymore. As we left, Joey grabbed a barbell handle from his drawer, a heavy metal pole just the right size for cracking someone’s skull with. I kept staring at it, lying there, gaining violent inertia with every second closer to Lake Temescal we came. The fucking pole was all I could look at.