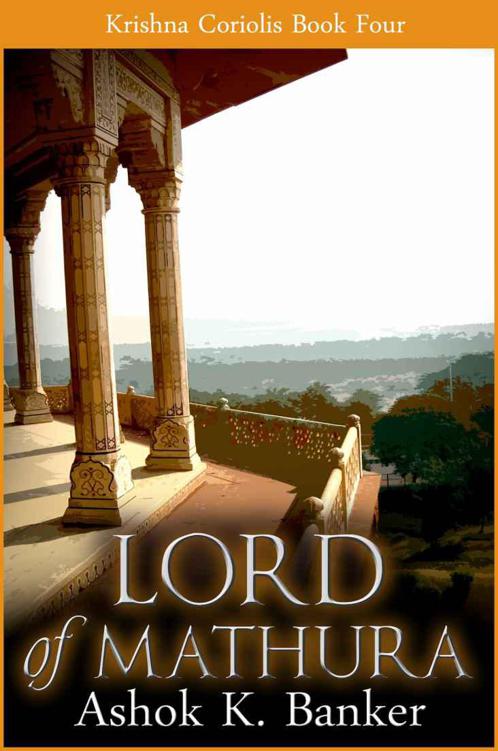

KRISHNA CORIOLIS#4: Lord of Mathura

Read KRISHNA CORIOLIS#4: Lord of Mathura Online

Authors: Ashok K. Banker

Contents

Also in the Krishna Coriolis Series

Also in the Krishna Coriolis Series

Also in the Krishna Coriolis Series

Also in the Krishna Coriolis Series

Also in the Krishna Coriolis Series

LORD OF MATHURA

Ashok K

.

Banker

KRISHNA CORIOLIS

Book

4

AKB eBOOKS

AKB eBOOKS

Home of the epics!

RAMAYANA SERIES®

PRINCE OF DHARMA

PRINCE OF AYODHYA & SIEGE OF MITHILA

PRINCE IN EXILE

DEMONS OF CHITRAKUT & ARMIES OF HANUMAN

PRINCE AT WAR

BRIDGE OF RAMA & KING OF AYODHYA

KING OF DHARMA

VENGEANCE OF RAVANA & SONS OF SITA

KRISHNA CORIOLIS SERIES™

MAHABHARATA SERIES®

MUMBAI NOIR SERIES

FUTURE HISTORY SERIES

ITIHASA SERIES

& MUCH, MUCH MORE!

only from

AKB eBOOKS

www.akbebooks.com

About Ashok

Ashok Kumar Banker’s internationally acclaimed

Ramayana Series®

has been hailed as a ‘milestone’ (

India

Today)

and a ‘magnificently rendered labour of love’ (

Outlook

). It is arguably the most popular English-language retelling of the ancient Sanskrit epic. His work has been published in 56 countries, a dozen languages, several hundred reprint editions with over 1.2 million copies of his books currently in print.

Born of mixed parentage, Ashok was raised without any caste or religion, giving him a uniquely post-racial and post-religious Indian perspective. Even through successful careers in marketing, advertising, journalism and scriptwriting, Ashok retained his childhood fascination with the ancient literature of India. With the

Ramayana Series®

he embarked on a massively ambitious publishing project he calls the Epic India Library. The EI Library comprises Four Wheels: Mythology, Itihasa, History, and Future History. The

Ramayana Series®

and

Krishna Coriolis

are part of the First Wheel. The

Mahabharata Series

is part of the Second Wheel.

Ten Kings

and the subsequent novels in the Itihasa Series dealing with different periods of recorded Indian history are the Third Wheel. Novels such as

Vertigo, Gods of War, The Kali Quartet, Saffron White Green

are the Fourth Wheel.

He is one of the few living Indian authors whose contribution to Indian literature is acknowledged in The Picador Book of Modern Indian Writing and The Vintage Anthology of Indian Literature. His writing is used as a teaching aid in several management and educational courses worldwide and has been the subject of several dissertations and theses.

Ashok is 48 years old and lives with his family in Mumbai. He is always accessible to his readers at www.ashokbanker.com—over 35,000 have corresponded with him to date. He looks forward to hearing from you.

PRARAMBH

1

The

song of the flute filled the hamlet of Vrindavan.

Its sweet mournful melody carried to the remotest eaves and highest treetops and no creature that heard it failed to be moved.

Its daily presence brought comfort and strength to the denizens of that secluded valley, assuring them that they were safe and secure in this little world away from the world at large, that someone powerful and benevolent watched over them constantly, and that any threat would be dealt with at once. But there was another message imparted by the flute: one embodied by the sweet sadness of its song. This said that life and all its pleasures were finite and would end someday, and all we could do was make the best of the time we have for it will not last. It mourned the lost brothers and sisters of the Vrishni who were here in voluntary exile from their beloved homeland, it mourned the tragedy that had befallen the Yadava nation as a whole, it shared the grief of love and loss, death and failure, war and vengeance.

The flute sang of things that could not be spoken, things that were felt but left unsaid, things that had happened before and would happen again, inevitably, but not now, not just yet. The flute song was the pause between battles, the respite between wars, the rare moment of peace between the violence of yesterday and the madness of tomorrow. The flute was what kept the Vrishni sane and whole and nourished them with the nectar of hope each fine day in Vrindavan. The flute was their reason for going on, for facing each new day with confidence, for living.

When the song was done, the hand that played the flute lowered the instrument. The player wiped the wooden reed on his brightly colored anga-vastra before tucking it securely into his waistband sash. Even now, despite all that had gone before, he was still just a boy.

Yet there was a sense of serenity about him that belied his years. His dark face could be sombre and brooding like a monsoon cloud yet when he smiled his white teeth flashed in that dark space like lightning against a pitch-black sky. His hot brown eyes gleamed with life, danced with intelligence. His smile tended to crease one cheek more than the other, giving him a sly rascally look that portended mischief. Unconcerned about his appearance and grooming, he nevertheless managed to always look fetching, almost girlishly handsome. In contrast to his brother’s fair-skinned bullish bulk, he was a slender dark calf.

Already, the mother gopis gossiped about what a handsome young man he would turn out to be and how some young gopi would be very lucky to have him as her mate. Child marriage was common among Yadavas but not always compulsory. In the case of a clan headman such as Nanda Maharaja, his sons could choose their mates when they pleased. The Vrishni, even more than other Yadavas, appreciated the finer emotions and the heart played as important a part in that choice as other factors such as clan, tribe, gotra and family. In Krishna’s case, he was already a prince among gopas and could have any gopi of his choice for a paramour and wife.