Kull: Exile of Atlantis (14 page)

Read Kull: Exile of Atlantis Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard

“There are ways,” purred the Valusian.

“Torture?” grunted Kull, his lips writhing in unveiled contempt. “Zarfhaana is a friendly nation.”

“What cares the emperor for a few wretched villagers?” blandly asked Ka-yanna.

“Enough.” Kull swept aside the suggestion with true Atlantean abhorrence, but Brule raised his hand for attention.

“Kull,” said he, “I like this fellow’s plan no more than you but at times even a swine speaks truth–” Ka-yanna’s lips writhed in rage but the Pict gave him no heed. “Let me take a few of my men among the villages and question them. I will only frighten a few, harming no one; otherwise we may spend weeks in futile search.”

“There spake the barbarian,” said Kull with the friendly maliciousness that existed between the two.

“In what city of the Seven Empires were you born, lord king?” asked the Pict with sarcastic deference.

Kelkor dismissed this by-play with an impatient wave of his hand.

“Here is our position,” said he, scrawling a map in the ashes of the camp-fire with his scabbard end. “North, Felgar is not likely to go–assuming as we do that he does not intend remaining in Zarfhaana–because beyond Zarfhaana is the sea, swarming with pirates and sea-rovers. South he will not go because there lies Thurania, foe of his nation. Now it is my guess that he will strike straight east as he was travelling, cross Zarfhaana’s eastern border somewhere near the frontier city of Talunia, and go into the wastelands of Grondar; thence I believe he will turn south seeking to gain Farsun–which lies west of Valusia–through the small principalities south of Thurania.”

“Here is much supposition, Kelkor,” said Kull. “If Felgar wishes to win through to Farsun, why in Valka’s name did he strike in the exactly opposite direction?”

“Because, as you know Kull, in these unsettled times all our borders except the eastern-most are closely guarded. He could never have gotten through without proper explanation, much less have carried the countess with him.”

“I believe Kelkor is right, Kull,” said Brule, eyes dancing with impatience to be in the saddle. “His arguments sound logical, at any rate.”

“As good a plan as any,” replied Kull. “We ride east.”

And east they rode through the long lazy days, entertained and feasted at every halt by the kindly Zarfhaana’an people. A soft and lazy land, thought Kull, a dainty girl, waiting helpless for some ruthless conqueror–Kull dreamed his dreams as his riders’ hoofs beat out their tattoo through the dreamy valleys and the verdant woodlands. Yet he drove his men hard, giving them no rest, for ever behind his far-sweeping and imperial visions of blood-stained glory and wild conquest, there loomed the phantom of his hate, the relentless hatred of the savage, before which all else must give way.

They swung wide of cities and large towns for Kull wished not to give his fierce warriors opportunity to become embroiled with some dispute with the inhabitants. The cavalcade was nearing the border city of Talunia, Zarfhaana’s last eastern outpost, when the envoy sent to the emperor in his city to the north rejoined them with the word that the emperor was quite willing that Kull should ride through his land, and requested the Valusian king to visit him on his return. Kull smiled grimly at the irony of the situation, considering the fact that even while the emperor was giving benevolent permission, Kull was already far into his country with his men.

Kull’s warriors rode into Talunia at dawn, after an all night’s ride, for he had thought that perhaps Felgar and the countess, feeling temporarily safe, would tarry awhile in the border city and he wished to precede the word of his coming.

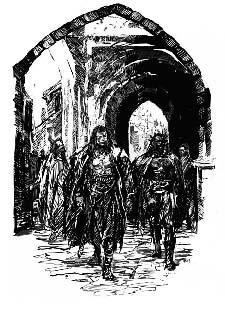

Kull encamped his men some distance outside the city walls and entered the city alone save for Brule. The gates were readily opened to him when he had shown the regal signet of Valusia and the symbol sent him by the Zarfhaana’an emperor.

“Hark ye,” said Kull to the commander of the gate-guards. “Are Felgar and Lala-ah in this city?”

“That I cannot say,” the soldier answered. “They entered at this gate many days since but whether they are still in the city or not, I do not know.”

“Listen, then,” said Kull, slipping a gemmed bracelet from his mighty arm. “I am merely a wandering Valusian noble, accompanied by a Pictish companion. None need to know who I am, understand?”

The soldier eyed the costly ornament covetously. “Very good, lord king, but what of your soldiers encamped in the forest?”

“They are concealed from the eyes of the city. If any peasant enters your gate, question him and if he tells you of a force encamped, hold him prisoner for some trumped-up reason, until this time tomorrow. For by then I shall have secured the information I desire.”

“Valka’s name, lord king, you would make me a traitor of sorts!” expostulated the soldier. “I think not that you plan treachery, yet–”

Kull changed his tactics. “Have you not orders to obey your emperor’s command? Have I not shown you his symbol of command? Dare you disobey? Valka, it is you who would be the traitor!”

After all, reflected the soldier, this was the truth–he would not be bribed, no! no! But since it was the order of a king who bore authority from his emperor–

Kull handed over the bracelet with no more than a faint smile betraying his contempt of mankind’s way of lulling their conscience into the path of their desire; refusing to admit that they violated their own moral senses, even to themselves.

The king and Brule walked through the streets, where the trades-people were just beginning to stir. Kull’s giant stature and Brule’s bronze skin drew many curious stares, but no more than would be expected to be accorded strangers. Kull began to wish he had brought Kelkor or a Valusian for Brule could not possibly disguise his race, and since Picts were seldom seen in these eastern cities, it might cause comment that would reach the hearing of those they sought.

They sought a modest tavern where they secured a room, then took their seats in the drinking room, to see if they might hear aught of what they wished to hear. But the day wore on and nothing was said of the fugitive couple nor did carefully veiled questions elicit any knowledge. If Felgar and Lala-ah were still in Talunia they were certainly not advertising their presence. Kull would have thought that the presence of a dashing gallant and a beautiful young girl of royal blood in the city would have been the subject of at least some comment, but such seemed not to be the case.

Kull intended to fare forth that night upon the streets, even to the extent of committing some marauding if necessary, and failing in this to reveal his identity to the lord of the city the next morning demanding that the culprits by handed over to him. Yet Kull’s ferocious pride rebelled at such an act. This seemed the most logical course, and was one which Kull would have followed had the matter been merely a diplomatic or political one. But Kull’s fierce pride was roused and he was loath to ask aid from anyone in the consummating of his vengeance.

Night was falling as the comrades stepped into the streets, still thronged with voluble people and lighted by torches set along the streets. They were passing a shadowy side-street when a cautious voice halted them. From the dimness between the great buildings a claw-like hand beckoned. With a swift glance at each other, they stepped forward, warily loosening their daggers in their sheaths as they did so.

An aged crone, ragged, stooped with age, stole from the shadows.

“Aye, king Kull, what seek ye in Talunia?” her voice was a shrill whisper.

Kull’s fingers closed about his dagger hilt more firmly as he replied guardedly.

“How know you my name?”

“The market-places speak and hear,” she answered with a low cackle of unhallowed mirth. “A man saw and recognized you today in the tavern and the word has gone from mouth to mouth.”

Kull cursed softly.

“Hark ye!” hissed the woman. “I can lead ye to those ye seek–if ye be willing to pay the price.”

“I will fill your apron with gold,” Kull answered swiftly.

“Good. Listen now. Felgar and the countess are apprized of your arrival. Even now they are preparing their escape. They have hidden in a certain house since early evening when they learned that you had come, and soon they leave their hiding place–”

“How can they leave the city?” interrupted Kull. “The gates are shut at sunset.”

“Horses await them at a postern gate in the eastern wall. The guard there has been bribed. Felgar has many friends in Talunia.”

“Where hide they now?”

The crone stretched forth a shrivelled hand. “A token of good faith, lord king,” she wheedled.

Kull put a coin in her hand and she smirked and made a grotesque curtesy.

“Follow me, lord king,” and she hobbled away swiftly into the shadows.

The king and his companion followed her uncertainly, through narrow, winding streets until she halted before an unlit huge building in a squalid part of the city.

“They hide in a room at the head of the stairs leading from the lower chamber opening into the street, lord king.”

“How do you know that they do?” asked Kull suspiciously. “Why should they pick such a wretched place in which to hide?”

The woman laughed silently, rocking to and fro in her uncanny mirth.

“As soon as I made sure you were in Talunia, lord king, I hurried to the mansion where they had their abode and told them, offering to lead them to a place of concealment! Ho ho ho! They paid me good gold coins!”

Kull stared at her silently.

“Now by Valka,” said he, “I knew not civilization could produce a thing like this woman. Here, female, guide Brule to the gate where await the horses–Brule, go with her there and await my coming–perchance Felgar might give me the slip here–”

“But Kull,” protested Brule, “you go not into yon dark house alone–bethink you this might all be an ambush!”

“This woman dare not betray me!” and the crone shuddered at the grim response. “Haste ye!”

As the two forms melted into the darkness, Kull entered the house. Groping with his hands until his feline-gifted eyes became accustomed to the total darkness he found the stair and ascended it, dagger in hand, walking stealthily and on the look out for creaking steps. For all his size, the king moved as easily and silently as a leopard and had the watcher at the head of the stairs been awake it is doubtful he would have heard his coming.