Lakota Woman (17 page)

Authors: Mary Crow Dog

Leonard Crow Dog praying.

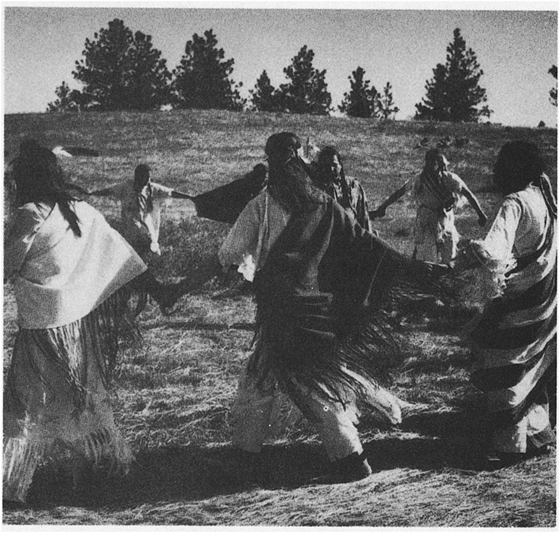

Revival of the Ghost Dance at Rosebud Reservation in 1974.

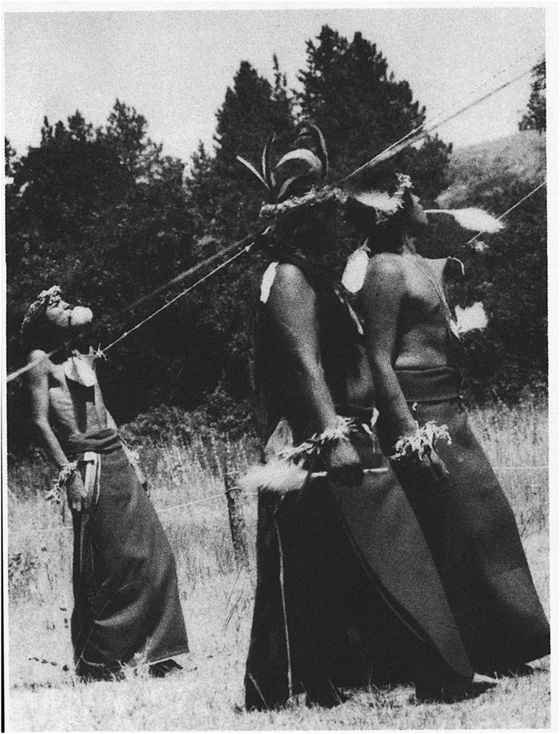

Piercing during the Sun Dance ceremony at Leonard Crow Dog’s place.

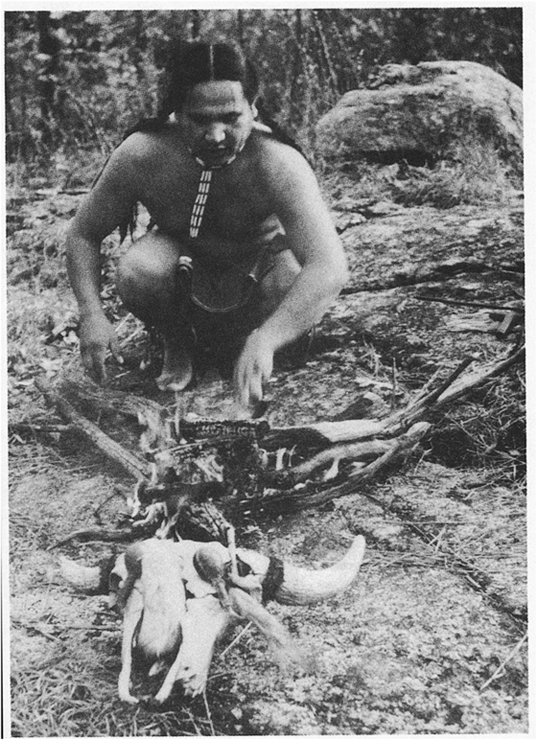

Leonard Crow Dog preparing for vision quest in 1973.

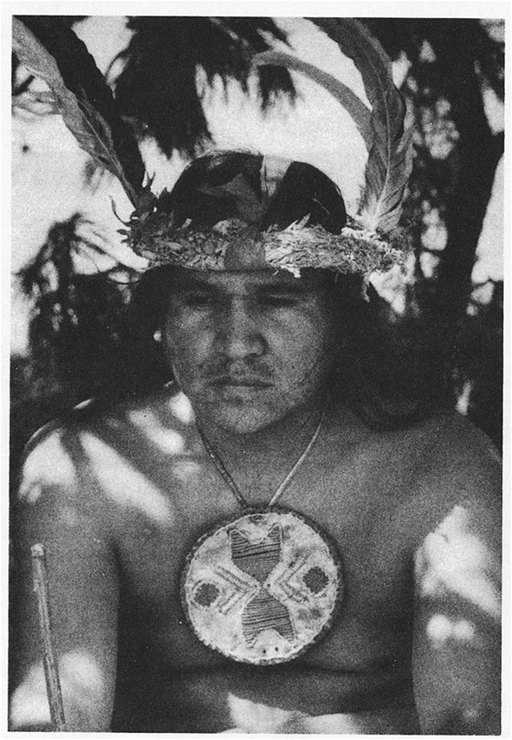

Sun Dancer Merle Left Hand Bull blowing on eaglebone whistle during Sun Dance.

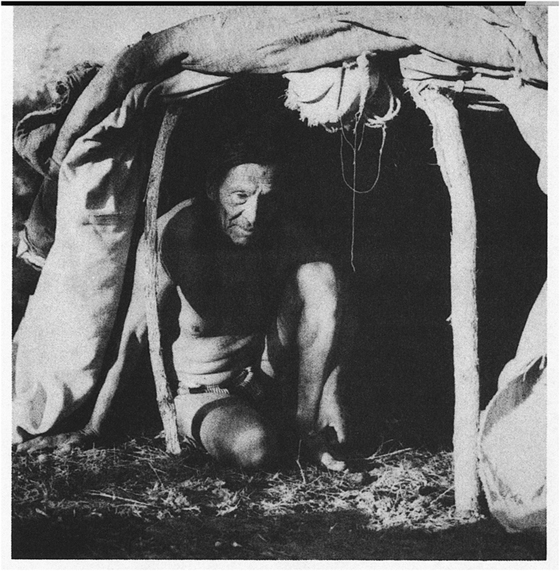

Henry Crow Dog in sweat lodge, 1969.

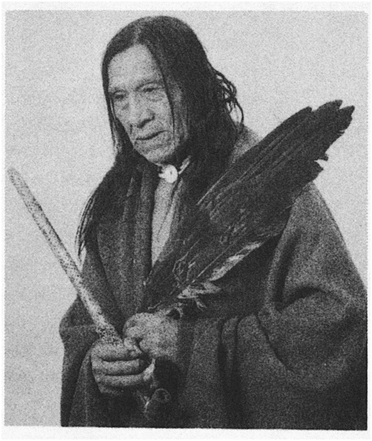

Henry Crow Dog before vision quest.

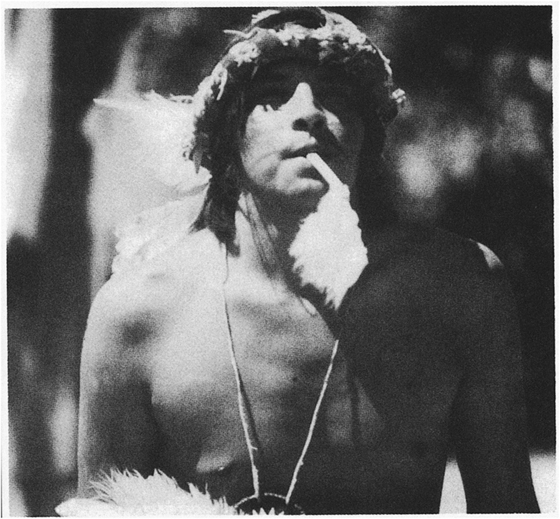

Leonard Crow Dog in Sun Dance regalia, 1973.

CHAPTER 10

The Ghosts Return

Eighty-five years ago

the ghost dancers thought

that by dancing

they could change the earth.

We dance to change ourselves.

Only when we have done this

can we try to change the earth.

—

Crow Dog 1974

I

t was the Ghost Dance religion which was at the core of the first Wounded Knee, and Indian religion as much as politics was also at the heart of the second Wounded Knee in 1973. By common consent, Crow Dog was the spiritual leader inside the Knee, and together with medicine man Wallace Black Elk he performed all the ceremonies. Crow Dog’s influence upon the spiritual and physical well-being of the occupiers was very, very strong. Outside, and not far from Wounded Knee, the oldest and most respected Sioux holy man, Frank Fools Crow, acted in support of us from his place at Kyle, doing as much for the Sioux people outside as Crow Dog did inside. All the medicine men of the Sioux Nation visited and supported us, but it was Crow Dog who revived the Ghost Dance, outlawed for over eighty years, right at Wounded Knee, during the siege.

Leonard did so many things. He performed the rituals and prayers, took a major part in all negotiations, operated upon gunshot wounds, healed the sick, and even took over for a while as chief engineer. The fires for the sweat lodge were kept going twenty-four hours a day, and almost every night we had a ceremony, such as a yuwipi or, on a few occasions, a peyote meeting. On solemn occasions men and women made flesh offerings by cutting pieces of skin from their arms, just as Sitting Bull had done in 1876, a few days before the Custer battle. Some of the leaders pierced their breasts as is done during a Sun Dance, thinking their suffering could help the people through spiritual power.

Every evening I went to a ceremony. These rituals were quiet, very quiet. One evening, after a ceremony, I was walking back to the other side of Wounded Knee where I stayed, and all along the creek I heard women crying, babies screaming, cannon shots, and the hooves of horses drumming on the earth. I was walking along Cankpe Opi Wakpala where our women and children had been killed in 1890. It was so strange, reliving this tragedy in a half dream, this recurring of a vision I had as a young girl after a peyote meeting. I still do not know what to make of it. Is it the vision of a tragedy still to come, of history repeating itself?

Every evening all the warriors took sweat baths to purify themselves. Leonard put his friend Wallace Black Elk in charge of most of these inipi ceremonies. One night Leonard himself was running the sweat, and when he and the others came out of the lodge the feds opened up on them, hitting the lodge and the tipi with their M-16s. Some men jumped into the shallow bunker nearby, but Crow Dog got stuck between the fireplace and the bunker and had to lie there, very exposed, for about two hours before he had a chance to make a dash for shelter. It was a miracle nobody got killed that day.

Before we had our first meeting with the government representatives trying to negotiate a settlement, everybody asked Leonard to perform a sunrise ceremony at Big Foot’s grave. He set up an altar and said: “Our most sacred altar is this hemisphere, this earth we’re standing on, this land we’re defending. It is our holy place, our green carpet. Our night light is the moon and our director, our Great Spirit, is the sun.”

Leonard was our chief doctor and all the white medics and volunteer M.D.s deferred to him. The white doctors had come to the Knee expecting to treat children’s and respiratory diseases. They had not thought that there would be firefights. They had no surgical equipment. So Leonard did all the operating. When Buddy Lamont got killed there were three other men with him in the bunker. One of them was hit four times, three times in the arm and once in the foot. The second man was shot in the hand and the third, Milo Goings, got a bullet in his knee. Leonard doctored them all. It took him less time than it would have a white doctor to take a bullet out and there never were any infections. He was using Indian medicine to treat the wounds. To take a bullet out, he first used porcupine quills and an herb, redwood, to make the flesh numb. Once this kind of Indian anesthesia began working—and it acted very fast—he went in with the knife, the same knife he uses to pierce the Sun Dancers. He sewed the wounds up with deer sinew and stopped the bleeding with sacred gopher dust, a medicine Crazy Horse had preferred above all others. To prevent infections and speed up the healing process, he used taopi tawote, wound medicine, I think in white botany it is called yarrow. He employed an herb called wina wazi hutkan, burr root, to stop internal hemorrhages. He treated respiratory diseases with the sweat bath and with teas made of several varieties of sage, and reduced fever with hehaka pejuta, the elk herb which the whites call horsemint. This is also a powerful love medicine. These were some of the Indian herbs which Leonard used. Pat Kelly, a white doctor from Seattle who came to the Knee to help us, had complete faith in Leonard. He always said that wounds treated by Crow Dog healed twice as fast as those treated by the white medics with their modern medicaments.

Rocky Madrid, a chicano medic, was hit in the stomach. It was a miracle that he did not get his guts blown out. He managed to walk back to the hospital and Crow Dog took the bullet out. Luckily it had not penetrated all the way into the stomach. Rocky said that Leonard was in and out with his knife almost before he knew it and that with Indian anesthesia he did not feel a thing. Leonard taught the white medics how to use his natural medicines and to say the proper prayers before treating a patient.

It was strange that Crow Dog was called upon to doctor machines as well as men. After Bob Free resigned as chief engineer, Leonard took over his job, too. When things broke down he fixed them. He had a real gift for that kind of work. As a kid he had learned how to repair cars. At the Knee he repaired the gas pumps and kept the electricity going. During the last few weeks it was cut off and we had to make do with kerosene lamps which we had found in the store. Part of Leonard’s job as chief engineer was to put up defense works. He supervised the building of bunkers, all of which had individual names, such as the Strong Heart or the Sitting Bull bunker. He engineered a defensive circle of mines. He put some boys to work pounding a hundred pounds of coal from the store into charcoal. Also from the store he got about a thousand light bulbs. These he filled with charcoal and battery acid. He put all these tiny light bulb bombs on one fuse, all the way around the perimeter, connected to a battery. They were strung on a wire and when one of the feds touched that it set off a spark which exploded the bulbs. Individually his tiny mines could not do much damage but they served well in keeping the marshals at a respectful distance. One thing Leonard did not do was to take up a gun and shoot. His being a medicine man forbade it.

The most memorable thing Leonard did was to bring back the Ghost Dance. I think he did this not only for us, the living, but also for the spirits of those lying in the mass grave. As I mentioned before, the Ghost Dance tradition has always been strong in our family. Leonard’s great-grandfather, the first of the Crow Dogs, was not only one of the earliest Ghost Dancers among the Sioux, but also one of their foremost leaders.

Back in 1889 a man came and told Crow Dog: “A new world is coming. A new power will strip off like a blanket this world which the wasičun has spoiled, and underneath will be the new world, undefiled and green. Walking on it we will meet our dead relatives whom the wasičun has killed, come to life again, coming to greet us. The buffalo, who have all disappeared into a great hole in a mountain to get away from the wasičun, will come out from their caves beneath the earth to fill up the prairie again with their countless herds. The father says so.” That man was Short Bull from our own Brule tribe, a famous warrior who had fought Custer.

Many men were soon traveling silently at night, on foot, on horseback, hidden in cattle trains, wandering hundreds of miles across the new railroad tracks and over the barbed-wire fences, traveling ghostlike, unseen and unheard by the wasičuns, spreading the same message from tribe to tribe.

Short Bull and his friends Kicking Bear and Good Thunder had received this message from Wovoka himself, the Paiute holy man to whom the Ghost Dance religion had been given in a dream on the day the sun had died. Wovoka had let them look inside his black Uncle Joe hat. In it they had seen the universe. They had looked into the hat and understood. The Piute dreamer made them die and walk on the new world that was coming. Then he made them come to life again. Wovoka had given them a new dance, new songs, and new prayers. He gave them a sacred eagle feather, an eagle wing, and scarlet face paint. Of the four songs he gave them, the first brought fog and white mist, the second brought snow and icy cold, the third, gentle rain, and the fourth, sunshine and warmth.

Life was so hard for our people—starving, fenced in, without horses or weapons. The message brought them hope. And so they began to dance and sing, to bring back the buffalo, to bring back the old world of the Indians which the wasičun had destroyed, the world they had loved so much and for whose return they were praying.

Crow Dog, together with his friends and relatives Two Strikes and Yellow Robe, joined Short Bull’s camp of Ghost Dancers, bringing all his followers along. They moved to Pass Creek where a sacred tree stood, which was good to dance around. They were dancing, too, at Sitting Bull’s camp at Standing Rock, at Big Foot’s place near Cheyenne River, even at Pine Ridge right under the wasičuns’ noses. The Ghost Dance was a religion of love, but the whites misunderstood it, looking upon it as the signal for a great Indian uprising which their bad consciences told them was sure to come. The whites were afraid, and the agents called in the army to put this new religion down.

At Pass Creek, Crow Dog’s people danced in a circle holding hands, wrapped in upside-down American flags symbolic of the wasičuns’ world of fences, telegraph poles, and factories which would also be turned upside down, as well as a sign of despair. They also dressed in special Ghost Dance shirts painted with star and moon designs and with the images of eagles and magpies. These shirts, the people believed, would make them bulletproof. Whirling in a circle for hours and hours, some dancers fell down in a trance, “died,” and in death wandered among the stars, spoke with their long-dead relatives, and experienced wonderful things which they described afterward.

Grandpa Dick Fool Bull was a child when he witnessed the Ghost Dance, but he remembered it well. A few years before he died over a hundred years old, Leonard taped him. This is what Dick Fool Bull said on his tape: “To start with I’ll tell you what I remember started the trouble, the big trouble. I happened to be at Rosebud, camping at Rosebud under guard—soldiers, cavalry—they rounded up all the fathers and grandfathers to make sure they don’t get away and mix up with that hostile bunch.

“My father was hauling freight from Valentine with his ox team. He’d go down there in the morning and camp down there and then he’d come back to Rosebud and unload. We heard there was a Ghost Dance going on, north of us by the falls at an Indian village called Salt Camp. My mother’s youngest brother took sick somehow and he wanted to see the dance, thinking that it might cure him. So they hooked up the team, the buckboard, and I rode over there with my uncle and my mother and my sisters. We got up there and when we got to level ground and could see the village we saw a lot of commotion going on, a lot of people on horseback and running around. When we got closer we could see a big circle of women and men, no children, just men and women clasping hands like they do now in a round dance.

“They all sing the ghost song, go round and round. I remember one fellow, he has a cartridge belt and a butcher knife, and a woman on each side of him. He acted like he was drunk, weaving back and forth, then he keeled over, falling on his face. Then he turned over. He lay there like dead and two men, the dance leaders, went over to him. One came with a fire, a pan full of glowing coals, and a big eagle wing. He put something on the fire which made a good-smelling smoke and with his big wing he fanned that smoke over that dancer, the one who was lying on his back. As he fanned the man he came to and sat up. The leader asked him what he had experienced.

“He said: ‘Well, there was a road from here to over there, a ghost road. I could not see it but I knew it was there and I walked on it. I came to a hill and a lone man stood there. When he saw me he sat down and waved to me to sit down beside him. I went up the hill and he showed me a big Indian camp, tipis, buffalo, horses, men hunting, women tanning, like in the old days, and that man told me, “That is your people over there, that’s where you’re going to be. That’s how you shall live. Now you go back. Teach your people. Teach them to live the old way.” ‘ And he gave that dancer a new song to remember when he woke up.

“And there was another dancer, not from our tribe, an Arapaho I think, and he got into a trance. He was like hypnotized, like not being where he was but somewhere else. In those days they had rifles and they wore shirts that were made out of canvas. And on the back they had the sun and the half-moon painted on each one. And the fringes were painted. They hung up those shirts on posts and they took their rifles and shot at them. And the bullets don’t pierce the shirts but are falling on the ground. And one man puts a ghost shirt on and says, ‘Come on, shoot at me,’ and they do and when the bullets hit the shirt they just fall harmlessly on the ground and the man isn’t hurt. And he tells the people, ‘With that sacred shirt, when you wear it, no bullet can hurt you.’ That’s the way it was.” This is how old Dick Fool Bull remembered it.

When you go toward Parmelee, in the bed of the Little White River, you come to a place where Leonard’s great-grandfather had a Ghost Dance in 1890. You can still make out the circle made by many footsteps. During that dance an old man called Black Bear swooned and fell down in a trance. He lay like dead for some time. All of a sudden he woke up. They saw this man standing, his arms raised and outspread. And in broad daylight they saw lightning strike and go into his hand, and when they cedared him, and he came to, he had a little rock in his hand, a rock from the stars.