Lamy of Santa Fe (49 page)

Authors: Paul Horgan

He was expected. A new friend who had a store in a small wooden building “on the corner of Fifteenth and Holladay” put him and his curate up for the night, and after a good night's sleep under a roof, they walked around to see the town. Machebeuf was astonished to

find that a small congregation, impatient for his arrival, had obtained a gift of two lots on the outskirts of town from the “express company, worth about $15 each, and had given the contract for the erection” of a brick church fifty by thirty feet in size. The specification gave the legal site as in “Denver City, Arapaho County, Kansas Territory.” Machebeuf said, “What folly to build a church so far from the town”âfor it stood actually on the prairie. He put up a seventy-five-dollar frame house behind the church, and soon enough both would be engulfed by the spreading city.

In 1858, a party of Kansas prospectors working near Pike's Peak had heard that gold had been found to the north, on a tributary of the Platte River, had made their way up to the site, had created a township and corporation there, and had returned to Kansas to excite prospective immigrants. In their absence, another party struck gold, set up their own camp of Aurora (named for their own town in Georgia) and soon a third party from Kansas arrived with a charter to organize a settlement given them by General James W. Denver, territorial governor of Kansas. The third place was named for him, and in due course all three areas merged in population as word spread and gold-seekers arrived in a growing rush. Gold in grains was to be had simply for the washing of the sand in the clear, shallow creeks of the region. Other gold was locked away in underground veins and was more laboriously mined by tunneling and by refining the mother ore. The earliest comers had no thought of settlingâonly of making quick fortunes and getting out. The rush came in a flood of people in 1859. Uncle Dick Wootten, a famous scout, opened the first saloon, serving the whiskey known as Taos Lightning, and a second soon followed under the name of the Hotel de Dunk.

It was a spontaneous society. Thieves or other criminals were given summary mob justice, andâthe usual frontier styleâwere often shot to death or hanged within minutes of their crimes. As always, there was an element which stood for law and order, but vastly the greater population consisted of lonely men, living a hard life, and taking loose pleasures in compensation, though at high cost. Gambling, whoring in dance halls, horse-racing, gun-fighting, claim-jumping and consequent killings, were common. The promise of riches and the less material but almost equally strong pull of the West as an idea brought party after party over the plains into the mountains. Many never forgot their first view of the Rockies from a hundred miles awayâagain the illusion was of cloud, often of a symbolic golden hue. Guide books were rushed through eastern presses to help the emigrants. Indian tempers were uncertain and many a survivor arriving at the camps could tell of massacre and pillage on the way.

But the energy of the whole nation seemed to be behind the movement westward, and already the shores of the continent were connected by a vital link which closed the gap between the steamboat terminus of St Joseph, where the Missouri River was almost four hundred yards wide, and the ports of the Pacific. This was the pony express. The riders went in relays of twenty-five miles each, taking two and a half hours, mostly at headlong gallop. Fresh horses waited at each stage, the saddle-bags were transferred, and the courier was off again, never to pause for any reason until his span was complete. A Colorado immigrant in 1860 after weeks on the plains longed for news, and seeing the Pony Expressâhe capitalized itâapproaching in a thunder of hooves, hoped for a little exchange. But “the Pony Express returning from San Francisco ⦠passed us like the wind and we could not get a single word of news.” It became a familiar, possibly comic, sight, the rider leaning forward in his saddle, scowling in the importance of his mission, his hat brim pressed flat against his crown by the wind, his driven pony, like the rider, distracted by nothing, as the pony's loyal triple beat faded at the gallop into the empty distance.

Beyond the open Platte River valley of Denver City rose the wonderful mountains with their infinite complexity of form. Entry into them followed creek and river beds, which were soon accompanied by the rudest of roads, leading to side canyons or hardly accessible slopes where mining camps were put up out of raw timber. The miner's life could hardly have been harder; yet camp after camp grew into village, then town, and "in some instances, cities which endured.

In the beginning, Denver City was the miner's only change from the camps, and with a nugget, or a little pouch of gold dust, he went, when he could, for the violent relief to be had in a town whose chief industry was the assuagement, in various ways, of the hungers of lonely men. One such remembered coming to town from the lost gulches.

We made a most woeful appearance. When we started out we had a gay suit of miner's dress. Only two weeks passed and we came back our clothes hanging in shreds from our backs, our hats in ribbons and scarcely affording us any protection from the sun. Our boots were left behind more than twenty miles back and our feet entirely bare and cut from the sharp jagged rocks. They had a thousand questions to ask us but before we would answer any of them we made them get us something to eat and a change of clothing. We did not have one for two weeks. It was almost as good as renewing life when we got new clothes and I felt as if it was worth going through all those hardships for the rare enjoyment of that hour.

By the time Machebeuf arrived, the city was already swelling with commerce and growth. Overland waggons brought goods to the wooden warehouses, including “to some extent the luxuries” of life. Hundreds came not to find gold in mines but in the pockets of the minersâbilliard-hall proprietors, the milkman ringing his bell as he went along the mud streets, even a theatre manager whose place was running “full blast with the Bateman sisters as the great attraction.” The United States mail had a regular route to Denver, and men lined up a hundred at a time to get their letters. The

Rocky Mountain News

already had a two-storey building with a pitched roof and a great sign at one end which read

PRINTING.

It was a mark of Denver's isolation when a miner, “coming round one corner ⦠found an auctioneer in full blast, selling as cheap and cheaper he said than the things could be bought

in America”

The young Bishop Lamy of Santa Fe in the 1860s

Marie Lamy, the bishop's niece, as a young girl. She came to America with him in 1849, was put to school with the Ursulines in New Orleans, and in 1857 Joined him at Santa Fe as a pupil in the Loretto Academy

Marie Lamy, while a pupil in the Loretto Academy, entered the novitiate, became a nun as Sister M. Francesca. She later became mother superior of the Loretto Convent at Santa Fe, and outlived her uncle by twenty-four years, dying in 1912

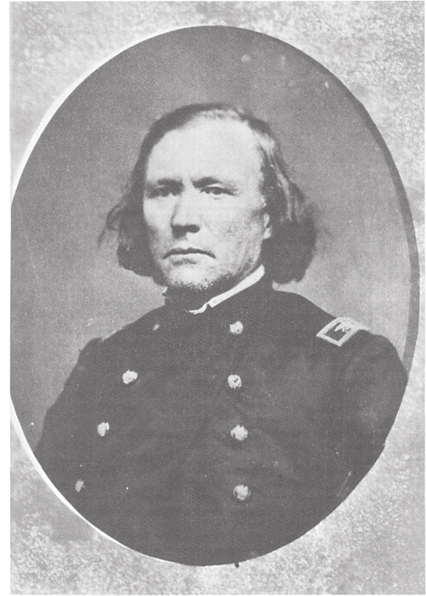

Christopher (Kit) Carson as colonel of the First New Mexican Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War period

Joseph Priest Machebeuf, Lamy's lifelong friend and lieutenant, as Bishop of Denver in his late years

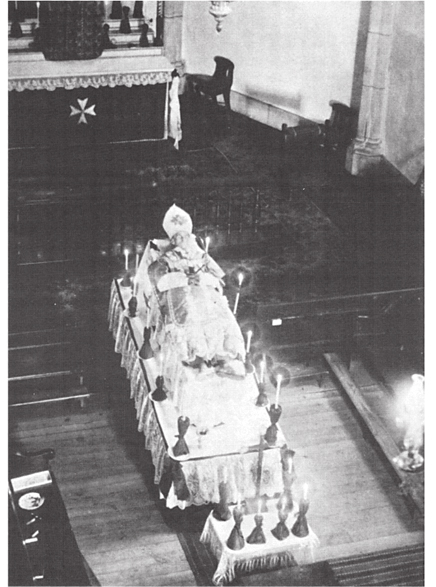

The aged and ailing Archbishop Lamy in retirement