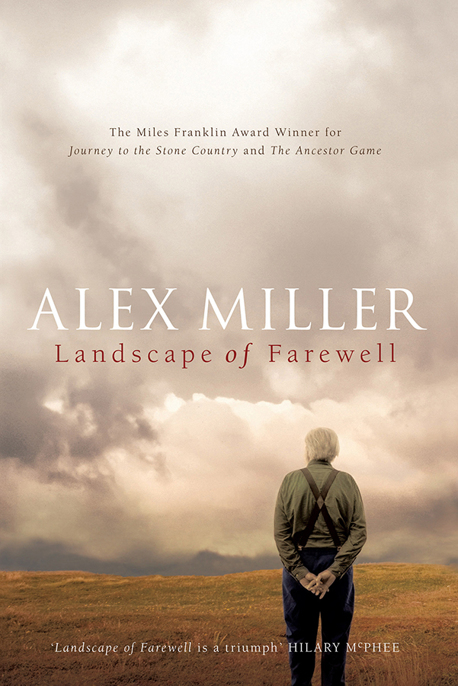

Landscape of Farewell

Read Landscape of Farewell Online

Authors: Alex Miller

PRAISE FOR ALEX MILLER

Prochownik’s Dream

‘

Prochownik’s Dream

is an absorbing and satisfying novel, distinguished by Miller’s enviable ability to evoke the appearance and texture of paintings in the often unyielding medium of words.’

—Andrew Riemer,

The Sydney Morning Herald

‘With this searing, honest and exhilarating study of the inner life of an artist, Alex Miller has created another masterpiece.’

—

Good Reading

‘

Prochownik’s Dream

… exemplifies everything we’ve come to expect and enjoy from one of Australia’s most accomplished authors … wonderfully absorbing and insightful.’ —

Sunday Telegraph

‘A beautiful novel of ideas which never eclipse the characters.’

—

The Age

Journey to the Stone Country

‘The most impressive and satisfying novel of recent years. It gave me all the kinds of pleasure a reader can hope for.’

—Tim Winton

‘A terrific tale of love and redemption that captivates from the first line.’

—Nicholas Shakespeare, author of

The Dancer Upstairs

Conditions of Faith

‘This is an amazing book. The reader can’t help but offer up a prayerful thank you: Thank you, God, that human beings still have the audacity to write like this.’

—

Washington Post

‘I think we shall see few finer or richer novels this year … a singular achievement.’

—Andrew Riemer,

Australian Book Review

‘Ambitious and convincing … highly readable … it explores the psyche of a woman torn between family and career with subtlety and grace.’

—

The New York Times Book Review

‘Rich and deeply emotional … a compelling portrayal of a young woman’s complicated feelings in the face of motherhood.’

—

Booklist

(starred review)

‘My private acid test of a literary work is whether, having read it, it lingers in my mind afterward.

Conditions of Faith

fulfils that criterion; I am still thinking about Emily.’

—Colleen McCulloch

The Sitters

‘Like Patrick White, Miller uses the painter to portray the ambivalence of art and the artist. In

The Sitters

is the brooding genius of light. Its presence is made manifest in Miller’s supple, painterly prose which layers words into textured moments.’

—Simon Hughes,

The Sunday Age

The Ancestor Game

‘Extraordinary fictional portraits of China and Australia.’

—

New York Times Book Review

‘A major new novel of grand design and rich texture, a vast canvas of time and space, its gaze outward yet its vision intimate and intellectually abundant.’

—

The Age

The Tivington Nott

‘

The Tivington Nott

abounds in symbols to stir the subconscious. It is a rich study of place, both elegant and urgent.’ —

The Age

‘In a virtuoso exhibition, Miller’s control never once falters.’

—

Canberra Times

ALEX MILLER

of

FAREWELL

Also by Alex Miller

Prochownik’s Dream

Journey to the Stone Country

Conditions of Faith

The Sitters

The Ancestor Game

The Tivington Nott

Watching the Climbers on the Mountain

For Stephanie

& for my friend Frank Budby, elder of the Barada

First published in 2007

Copyright © Alex Miller 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The

Australian Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

| This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory board. |

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web:

www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Miller, Alex, 1936–.

Landscape of farewell.

ISBN 978 1 74175 375 2

I. Title.

A823.3

Set in 11.5/17.5 pt Fairfield Light by Midland Typesetters, Maryborough, Victoria Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

From where rises the high tide of desire, of expectation, of an obsession with sheer being defiant of pain, of the treadmill of enslavement and injustice, of the massacres that are history?

George Steiner

1

Agamemnon’s edict

On examining my reflection in the hallstand mirror before leaving for the conference that morning, it was not my imminent death nor the poor quality of my paper that concerned me, but that I was in need of a haircut and had once again forgotten to shave. Winifred would have run her fingers along the back of my neck and reproved me,

You need tidying up!

As if I were a neglected room in her house. Winifred never had a house of her own, but in the ideal life of her imagination I am confident she had lived in one. For all the forthrightness of her modern feminist spirit, there was something immovably old-fashioned in Winifred’s secret longings and I am sure she saw herself, in this life of her interior fantasies, as the broad-hipped, bosomy mistress of a grand establishment with a vast brood of noisy and unruly children and large dogs.

We never talked about it. I just knew it, the way I knew her mood before she came into a room. Could that be where she had gone? Not to nothingness, but teleported to her true home when the summons came? Although I am an unbeliever, I devoutly wished such a blessing on her. For she was a woman who deserved to meet her true—indeed her ideal and imaginary—self one day. Which I cannot say of everyone I meet.

She seemed to stand behind me that morning as I examined my reflection in the mirror, unhappy that her husband, Professor Max Otto, for whom she once possessed ambitions, was not to cut a distinguished figure in front of his colleagues on the occasion of his last appearance before them, but was to be remembered by them at the end as a dishevelled, grieving, defeated old man. But perhaps that is too harsh. I am of average height and a little stooped these days, owing to the persistent pain of a mildly arthritic spine, and my hair, which in my youth was glossy and abundant, floats about at the back of my head like a luminous nimbus. My eyes too have faded—I had not expected this. Once a lustrous amber of great depth and clarity, my eyes are now a pale mud colour and are inclined to water, as if I am forever on the point of weeping—as I should be—or have been peeling onions. And speaking of onions, the skin of my face and neck has become thin and papery, and several of those darkly discoloured patches have appeared on my forehead. I resent this deterioration in my appearance more even than the daily allotment of pain. Until

well into my middle years I enjoyed an unblemished complexion, which I no doubt owed to a distant Barbary ancestor. I took this blessing for granted as something that was mine for life, as if it were the unearned due of class or breeding. Absurd vanity! I am able to detect only the faintest remains of that glorious past today. Now I look on a landscape arid and deserted, where once a gay society flourished amid ripening pomegranates and purple grapes, the splash of fountains and cool sounds of laughter from the grove on summer evenings, from where the erotic imploring of the oud aroused our lusts …

But I exaggerate. If only it ever had been thus.

I ran my fingers through my ghostly hair, and touched with the forefinger of my right hand a flaky darkness above my left eye, then patted my inside pocket to make certain I had not forgotten my paper and my glasses, and turned from the mirror and went downstairs into the fresh morning. There was the mahogany glint of horse chestnuts littering the footpath and the grass verges. The fine old trees along Schlüterstrasse were clinging to the last of their leaves—as we humans cling to life and to memories beyond their season. It was that brief, charmed period in Hamburg before the cold arrives, when the weather can still be relied upon to be fine, and even reminiscent of summer. It did not seem inappropriate to me that I planned to end my life on such a day. I had written my paper without conviction, obedient to a duty felt more towards the dead than the living.

There had been no joy in it. It had been a task imposed on me by the grim moral overseer who rules my life—my conscience, let us say. To claim now that I understood then my true motives for persisting with it would be a lie. Perhaps I persisted because I unconsciously desired a

reason

to persist. Who knows? I cannot truly say what my deeper motives were. I did not know them then and I do not know them now. I had postponed my death in order to write this valedictory paper because my daughter told me Winifred would have wanted me to do it. That was all. I composed it with only the most fleeting moments of pleasure and forgetfulness, and entirely without those surprising instants of inspiration that make intellectual labour worthwhile. Its arguments were concocted from yesterday’s leftovers, those stale thoughts out of that mouldering store of notes which I had preserved for thirty years—if preserved is the word for it—in the carton on top of my bookshelves in my study. I dug about in the cold ashes of that youthful folly and

came up

with something for this occasion. I hoped no one would notice how second rate it was, or that if they did notice they would not take offence, but would forgive this faltering of my advanced years and greet it with forbearance and silence.

As I walked down the front steps of our apartment building, little birds flew up at my approach. The publisher’s unhappy wife from the apartment below mine, Lydia Erkenbrecht, herself a published poet, had scattered crumbs from her table for them.

Or perhaps, more prosaically, not having a family of her own to feed and therefore having few crumbs on her table, the good woman purchased packets of birdseed from the supermarket for this purpose. At any rate, these little street birds were now her family—starlings and sparrows for the most part, with the occasional avuncular pigeon. I had noticed how shamed she was whenever my sudden appearance in the entryway to our building interrupted this pathetic substitution. But she kept on with it, and now the birds had come to rely on her, and she possessed, besides her poetry, if not love, then an object to her persistence rather less pathetic than my own desperate insistence on delivering my last paper to the conference in Aby Warburg’s old library.