Las Christmas (9 page)

Liz Balmaseda

Liz Balmaseda, a columnist for the

Miami Herald

,

was awarded the

1993

Pulitzer Prize for commentary. She was

Newsweek'

s

Central America bureau

chief, based in El Salvador, and a field producer for NBC News based in Honduras.

The National Association of Hispanic Journalists awarded her the first prize for

print in the Guillermo Martinez-Márquez contest; and she was honored by the

National Association of Black Journalists for her commentaries on Haiti.

NEXT YEAR IN HAVANA

THERE ALWAYS SEEMED to be that one lucky lechón, plumped by nostalgia, marinated by exile politics, and always in the endâ that lucky pigâspared by Fidel.

It was the one the old Cubans in Miami perennially vowed to consume in Havana the next Nochebuena.

“Oye chico, el año que viene el lechoncito lo comemos allá . . .”

Over there.

This would be a

lechón

slaughtered at dawn, skewered with particular satisfaction, lowered into an earth hole in the back yardâor perhaps into one of those tin contraptions they use in

el exilio,

called “

La

Caja China.

” It would be slow-roasted to perfection as morning dissolved into afternoon, the cousin population swelled inside the kitchen, and in a rustle of palms the strains of triumph filtered into the night, serenading the martyred

lechoncito

like a Willy Chirino song.

We all asked Santa for bicycles and Barbies.

Mami and Papi and Abuelo and Abuela asked for Christmas in Cuba.

For as long as I can remember, Nochebuena Miami-style has been a feast of fantasy. We would spray our winter wonderlands upon the sliding glass door in the Florida room

â¡Feliz

Navidad!

/snowflake/snowflake/snowman/candy caneâoblivious to the contrast of the scene outside, the palm trees and banana trees and oranges and mangos, the Virgencita de la Caridad shrine, the Slip-n-Slide, and the basketball net.

We celebrated a stream of Nochebuenas in Hialeah, the

viejos

invoking the spirits of long-ago celebrations as their sons and daughters picked apart the Miami Dolphins' starting lineup. Our unwitting stabs at assimilation left us in a bizarre time capsule. Consider the juxtaposition of Celia Cruz, Benny Moré, and Joe Cuba with Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, and Vixen.

My uncle sang rum-soaked tangos. My cousin sang Charles Aznavour songs. I chased her into startling octaves with my guitar. We drank eggnog and nibbled

turrón.

And sometime during the night, as inevitably as Christmas would dawn the next day, somebody in the house cried for those left behind in Puerto Padre, Cubaâthose who seemed to exist in another dimension, a sad, gray state of inertia.

On Christmas, we could produce evidence of our Cuban roots at the dinner table and on the dance floor. But no amount of black beans and

yuca con

mojo

and cha-cha-chá could summon all of Cuba to West Hialeah, Dade County, Florida. The nostalgia-bound had to settle for the fantasy.

In the meantime, we all thought ourselves to be pretty American. After all, we had the American Christmas routine down. We had accomplished lay-away and the mall. We anticipated Santa like everybody else. (Of course we knew he had to make extra stops at Cuban families' homes, considering how many cousins and second cousins and aunts and great-aunts and uncles we had.)

What seemed to make us different from

los americanos

was that extra

lechón,

the one always granted a stay of execution when it became clear Nochebuena, once again, would be in Miami.

Over here.

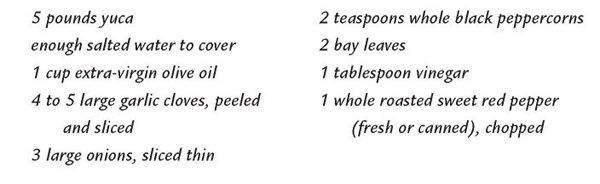

Yuca

al

Escabeche

YUCA IN GARLIC SAUCE

Yuca is a root vegetable that grows in the tropics. It can be found in the freezers of many supermarkets that carry tropical produce. Esmeralda's mother, Ramona Santiago, makes this dish the night before she serves it, but she prefers to eat her portion warm, right after it's prepared. It's equally delicious at room temperature.

Boil yuca in salted water to cover for 30 minutes or until it can be pierced with a fork but is not too soft. Drain. Slice into 1½-inch-wide slices. Transfer to heat-proof serving dish.

Heat oil in a cast-iron skillet. Add garlic and cook, stirring, just until golden. Add onions, peppercorns, and bay leaves. When onions begin to turn transparent, add vinegar. Add chopped red pepper and cook until just heated. Do not overcook.

Pour sauce over yuca in the dish. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Estela Herrera

Estela Herrera grew up in Mendoza, Argentina. She has lived in the United States

since

1968

, working extensively as an educator and a journalist in the Spanish-languagemedia. In

1991

, she received the National Association of Hispanic

Publications Award for Outstanding Editorial Column. She currently teaches at

the University of California, Los Angeles, and is working on her first novel.

NURTURING THE WILD BEAST OF CHRISTMAS

IT WAS MID-NOVEMBER in the little western Argentine town of Luján de Cuyo and the heat was relentless. Summer was fragrant with the sweet smell of melons and peaches, a prelude to the annual bounty of Christmas delicacies. Only one more month and these fruits, together with cherries, early apples, and apricots from the neighboring orchards would mingle happily with imported bananas and pineapples in the colorful concoctions that kept the women of the household busy for days peeling, cutting, cooking, and baking.

The air was full of expectations, of foods to enjoy, of people to see. Father had left early that morning, and when I asked why he hadn't taken me along I was hushed and told I should keep quiet because he was bringing home a surprise. And he certainly did.

We lived at the edge of the town, between the asphalt and the vineyards. From our house we could see the endless, orderly rows of green vines that turned red and yellow in the fall against the blue backdrop of the mountains. The Andes were always blue and mysteriously dangerous: so many stories of people who found their death at the bottom of an abyss or in the snow of a peak. There were no trees and certainly no vineyards on the harsh, rocky slopes.

Father had gone to the mountains that day to meet one of the few people who were, as Auntie put it, either so desperately daring or so desperately poor as to scrape a living from the tough and scant wild bushes that were all the mountains had to offer. When he came back, late and covered with dust, he was holding in his arms a small, warm, and trembling black creature.

“A baby goat,

nena.

Do you like it?”

I loved it instantly! I hardly slept that night, stirred by the anticipation of all the things I could do with the new member of the household. The following morning, I announced my plan over the breakfast table. I was going to feed it twice a day and take it to the vineyards for a walk. At night I was going to bring it indoors so it wouldn't be afraid of the dark. “None of that nonsense,” said Father, particularly bringing it into the house. The baby goat was to be kept in a little shed, improvised with chicken wire in the back patio, and I should not involve myself with it at all.

The rules were soon violated. I fed the goat as often as I could without being seen. In the afternoons, when the house succumbed to the heavy stupor of the siesta and everything stood still for two or three hours, I took it to the vineyards where I pointed it to the tender grasses and clover leaves that grew abundantly from the rich soil. “So much better than the thorny weeds of the mountains, don't you think? You will never have to eat them again. I will never let you go back, my poor

chivito.

”

In time, the copious leftovers in the shed led the grown-ups to discover my secret activities, but they didn't get very angry. In fact, they seemed to tolerate it with a bit of amusement. So I felt free to talk about my new friend. I struggled for days to find the perfect name for it and was ecstatic when somebody suggested Azabache. Jet stone. I was very young then and still blessed with a sense of astonishment when confronted with the obvious or the banal. I thought the name was strikingly original and so appropriate.

Azabache was a constant source of pleasure. The way its big eyes looked at me, its clumsy walk on the coarsely tilled soil beyond the asphalt, or the way it jumped and frolicked for no reason at all. I lived with and for Azabache.

By mid-December, Azabache had grown considerably while the adults' amusement with my obsession had sharply dwindled. Christmas preparations had begun full tilt and the house was a harried tumult of skirts coming and going, cleaning, polishing, shopping, planning. The Nativity scene was disinterred and the peeling paint on San José's cloak had to be retouched. The aroma of freshly baked

pan dulce

wafted from the kitchen, redolent with vanilla and candied fruit. Nobody noticed I had stolen some of the sugary lemon and orange rinds. I was so proud of myself that I was taken aback when Azabache met my offering with utter indifference. It refused to even taste them. A few days later, the pineapples and bananas were bought and placed in the warmest corners of the house to ensure their precise ripeness for the

clericó,

the fruit salad of the season, laced with orange juice for children, with champagne or vermouth for adults.

That holiday season my days were divided between the back patio and the vineyardsâI hardly visited the kitchen. Azabache was far more fun than the adults who had grown increasingly silent. But the fact that they lowered their voices when I came in or avoided my eyes bothered me only a little, since I had already experienced the whimsical ways of grown-ups, who were always changing the rules for obscure reasons or no reason at all. God only knew why they were acting so peculiar. Was Father angry at them? Just too much to do? After all, Mother and the other women were really very busy frying flaky quince turnovers, plucking chickens, and pressing the stuffed beef rolls for the

matambre.

No time for silly conversations with me. They needed to prepare the bite-size beef

empanadas

and the diminutive

sandwiches de miga,

moist towers of

pain de mie,

ham, red pimentos, cheese, and tender lettuce.

On the night of December 23 I went to bed happy knowing that cousins Irma, Amanda, and MarÃa Luisa were coming. We would all take Azabache for a walk, and in the early evening, when the heat had eased, help set the tables in the garden. We would eat many wonderful treats and play until past midnight. We would talk about the gifts we were expecting on January 6 from the Three Wise Kings, while trying to keep count of the firefliesâour favorite summer pastimeâshouting over the deafening choir of crickets. Mother and her sisters would blame our loudness, as they always did, on my father's largess in allowing us to drink a little alcoholic apple cider.

I slept soundly only to be awakened by a loud, sharp scream such as I never heard before. It came from the back patio, lacerating the early morning light and stabbing me in the heart. There was nothing in the world but that scream and my pain. And suddenly I knew. I understood the silence of the previous days and the women's feigned indifference toward me. I jumped out of bed and rushed to the front door. I ran out of the house in a frenzy, choked by my own scream stuck in my throat. I ran into the vineyards, stumbling on the moist soil, toward the blue mountains where Azabache had come from and I knew he would never, ever, go back.

It was the first and last time that Christmas roast goat, a regional delicacy, was prepared at our house.