Lawless

Authors: John Jakes

The Kent Family Chronicles (Book Seven)

John Jakes

Introduction: Answering the #1 Question

Chapter I “A Dog’s Profession”

Chapter VI In the Studio of the Onion

Chapter IX Colonel Lepp Insists

Chapter XIII On the Chelsea Embankment

Interlude

“And Thou Shalt Smite the Midianites as One Man”

Chapter V “The Lucy Stone Brothel, West”

Chapter VI Invasion at Ericsson’s

Chapter XI Decision in the Rain

Interlude

A Shooting on Texas Street

Chapter IV The Hearts of Three Women

Chapter VII Among the Goldhunters

Chapter VIII Death in Deadwood

Chapter XI The Man in Machinery Hall

Chapter XIV At the Booth Association

Chapter IV “Hell with the Lid Off”

Chapter VII Call to Forgiveness

Chapter IX From out of the Fire

Chapter XIII The Law and the Lawless

Answering the #1 Question

I

N Q & A SESSIONS, WRITERS

are repeatedly asked one question above all others: “Where do you get your ideas?” In the case of

The Lawless,

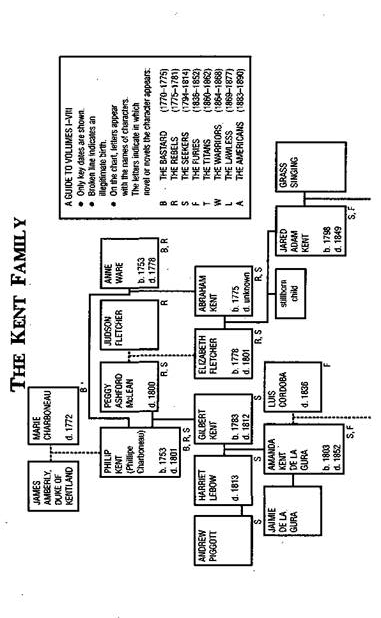

the seventh novel about the Kent family, I can confidently point to several sources.

I’ve said many times before that I’ve always relished the history of the American West. It has a place in the novel, in the sequences dealing with Jeremiah’s unhappy descent into a life of outlawry.

My admiration for the French Impressionists is long-standing and that, too, is reflected in the book’s opening section, which finds Matthew Kent in Paris, hanging around with some of the young, and as yet unappreciated, painters who would profoundly influence modern art. Among them is Matt’s unruly friend Cézanne.

Eleanor’s early career as an actress in a touring version of

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

comes from my lifelong love of the stage. These road company adaptations of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s blockbuster were called “Tom Shows,” and their performers “Tommers,” which I used for a chapter title. Tom Shows remained a staple of American theater well into the twentieth century.

It’s possible that Gideon Kent became a labor organizer because, early in my life, my parents and I lived for a few years in Terre Haute, Indiana, under the long shadow of the legendary union organizer and socialist Eugene Debs. At the time I had no interest in Debs; besides, my parents, along with most of Terre Haute, dismissed him as a radical who didn’t fit in as a proper citizen of Indiana. Ironically, Debs’s home has become a tourist attraction, much as sites in Montgomery, Alabama, connected with the once-reviled Martin Luther King are now embraced by the local chamber of commerce and promoted as important places to visit.

But the most specific answer to the question about ideas can be found in a dark room in a building at the south end of Chicago’s Lincoln Park. I visited the room many times as a youngster, gazing with awe and fascination at the scenes re-created in miniature behind glass windows: eight of them, as I remember.

The place is the Chicago Historical Society, one of the nation’s finest museums and research facilities. The dark room at the CHS contained a series of dioramas, or models, depicting Chicago at various times in its past. The diorama that drew my interest most often showed the city, under a flickering red sky, being devoured by the Great Fire of 1871. Somehow that scene buried itself in my imagination, to be recalled and used at some unknown moment in the future. This turned out to be the sequence in

The Lawless

that finds Gideon trapped in, and trying to escape from, the Great Fire.

When I started this new introduction, I asked the Chicago Historical Society whether the dioramas still exist. Lesley Martin of the CHS Research Center assured me that they do and in fact were recently featured in a photo piece in the

Chicago Tribune.

I was delighted to hear that not everything I knew and loved as a kid has been washed away by contemporary culture.

Thus, for this second-to-last volume of

The Kent Family Chronicles,

I can, for a change, answer the question about the springboard for ideas. I wish it were that easy for every book I’ve written.

The Lawless

remains one of my favorite novels in the series, because it encompasses so many aspects of history that have always fascinated me, not the least of them that harrowing image of Chicago burning. I thank my friends at New American Library for returning this and all the other volumes in the Kent saga to new life in these excellent new editions.

—John Jakes

Hilton Head Island,

South Carolina

“Pistols are almost as numerous as men. It is no longer thought to be an affair of any importance to take the life of a fellow being.”

October 13, 1868:

Nathan A. Baker,

editorializing in the

Cheyenne Leader.

“What is the chief end of man?—to get rich. In what way?—dishonestly if we can; honestly, if we must. Who is God, the one only and true? Money is God. Gold and Greenbacks and Stock—father, son, and the ghost of same—three persons in one; these are the true and only God, mighty and supreme …”

September 27, 1781:

“The Revised Catechism”

by Samuel Clemens,

published in the

New York Tribune.

The Dream and the Gun

i

T

HEY HUNTED BUFFALO

and lived in the open, away from the settled places. That sort of life tended to keep a man fit. But sometimes even the most robust constitution couldn’t withstand foul weather. So it proved with Jeremiah Kent in April of 1869.

Three days of exposure to fierce wind and pelting rain left him sneezing. Two days after that, he and his companion made camp in a hickory grove. Jeremiah rolled up in his blankets and surrendered to fever. Kola, the Oglala Sioux with whom he’d traveled since early ’66, kept watch.

After sleeping almost continuously for forty-eight hours, Jeremiah woke late at night. He saw Kola squatting on the other side of the buffalo chip fire, a dour look on his handsome face. Between Jeremiah and the Indian lay the cards of an uncompleted patience game Kola had started to pass the time. Over the past couple of years, whenever they’d had nothing else to do, Jeremiah had tried to teach his friend all the card games he knew. The Indian liked cards and had learned to shuffle and deal almost as fast and expertly as his mentor.

Jeremiah struggled to rise on one elbow. The fever still gripped him, distorting sounds: the rustle of new leaves in the spring breeze; the purl of water out of a limestone formation behind the grove; the occasional stamp or snort of one of their long-legged calico ponies. From his friend’s expression, Jeremiah knew something bad had happened. He licked the inside of his mouth. The fever made his teeth feel huge, his head gigantic. “You ought to sleep once in a while,” he said.

“The sickness has not passed. I will keep watch.”

“That all you’re fretting about, the sickness?”

The Sioux glanced into the wind-shimmered flame.

“Something’s sticking in your craw. What is it?”

The Sioux was three years older than Jeremiah, and his true

kola,

his sworn friend for a lifetime. Jeremiah had found the Indian on the prairie, nearly beaten to death by one of his own tribe; the beating was punishment for adultery. He’d cared for the Indian until he recovered, as Kola was caring for him now.

The young man’s bleary stare fixed on the Indian, prodding. “Come on. What?”

Kola sighed. “I did sleep a little tonight. While I slept, a vision came.”

The various branches of the Sioux tribe put great stock in visions. Clearly Kola’s had upset him. Jeremiah tried to put him at ease with a laugh and a wave. “Listen, I’m the one with the fever and the dreams.”

“Dreams of what?” Kola asked instantly. Jeremiah’s grin widened. “Women. Plump women.”

Kola grunted. “Better dreams than mine. I dreamed a dark thing.”

“Tell me.”

Looking at him with eyes that brimmed with misery, Kola said, “I dreamed I saw you with your guns again. I saw the guns in your hands.”