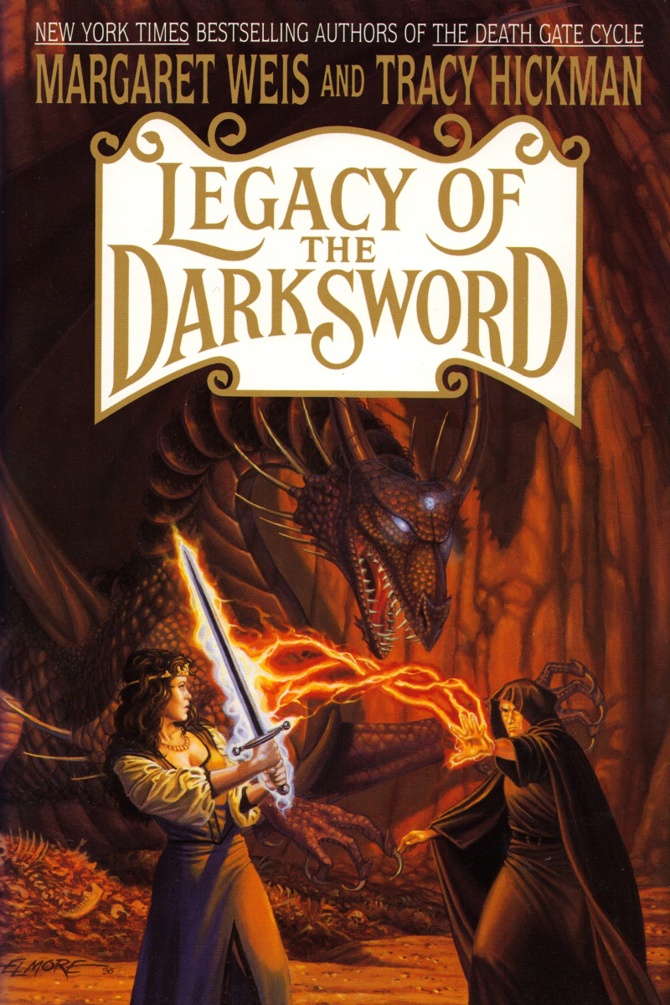

Legacy of the Darksword

Read Legacy of the Darksword Online

Authors: Margaret Weis,Tracy Hickman

Legacy

of the Darksword

The

Darksword Setting

Subsequent

volume

Dedicated

to all our readers who keep asking us, “

And then

what

happens?”

Finally, a child may be born to

the rarest of all the Mysteries, the Mystery of Life. The thaumaturgist, or

catalyst, is the dealer in magic, though he does not possess it in great

measure himself. It is the catalyst, as his name implies, who takes the Life

from the earth and the air; from fire and water, and, by assimilating it within

his own body, is able to enhance it and transfer it to the magi who can use it.

FORGING

THE DARKSWORD

S

aryon, now somewhere in his

sixties or seventies, as reckoned by Earth time, lived very quietly in a small

flat in Oxford, England. He was uncertain of the year of his birth in

Thimhallan, and thus I, who write this story out for him, cannot provide his

exact age. Saryon never did adapt well to the concept of Earth time relative to

Thimhallan time. History has meaning only to those who are its products and

time is but a means of measuring history, whether it

be

the history of the past moment or the history of the past billion moments. For

Saryon, as for so many of those who came to Earth from the once-magical land of

Thimhallan, time began in another realm—a beautiful, wondrous, fragile bubble

of a realm. Time ended when that bubble burst, when Joram pricked it with the

Darksword.

Saryon had no need for measuring

time anyway. The catalyst (though no longer required in this world, that is how

he always termed himself) had no appointments, kept no calendar, rarely watched

the evening news, met no one for lunch. I was his amanuensis, or so he was

pleased to call me. I preferred the less formal term of secretary. I was sent

to Saryon by command of PrinceGarald.

I had been a servant in the

Prince’s household and was supposed to have been Saryon’s servant, too, but

this he would not allow. The only small tasks I was able to perform for him

were those I could sneak in before he was aware of it or those which I wrested

from him by main force.

I would have been a catalyst myself,

had our people not been banished from Thimhallan. I had very little magic in me

when I left that world as a child, and none at all now after living for twenty

years in the world of the mundane. But I do have a gift for words and this was

one reason my prince sent me to Saryon. Prince Garald deemed it essential that

the story of the Darksword be told. In particular, he hoped that by reading

these tales, the people of Earth would come to understand the exiled people of

Thimhallan.

I wrote three books, which were

immensely well received by the populace of Earth, less well received among my

own kind. Who among us likes to look upon himself and see that his life was one

of cruel waste and overindulgence, greed, selfishness, and rapacity? I held a

mirror to the people of Thimhallan. They looked into it and did not like the

ugly visage that glared back at them. Instead of blaming themselves, they

blamed the mirror. My master and I had few visitors. He had decided to

pursuehis study of mathematics, which was one reason that he had moved from the

relocation camps to Oxford , in order to be near the libraries connected with

that ancient and venerable university. He did not attend classes, but had a

tutor, who came to the flat to instruct him. When it became apparent that the

teacher had nothing more to teach and that, indeed, the teacher was learning

from the pupil, the tutor ceased to make regular visits, although she still

dropped by occasionally for tea.

This was a calm and blessed time

in Saryon’s tumultuous life, for—although he does not say so—I can see his face

light when he speaks of it and I hear a sadness in his voice, as if regretting

that such a peaceful existence could not have lasted until middle age faded,

like comfortable jeans, into old age, from thence to peaceful eternal sleep.

That was not to be, of course,

and that brings me to the evening that seems to me, looking back on it, to be

the first pearl to slide off the broken string, the pearls that were days of

Earth time and that would start falling faster and faster from that night on

until there would be no more pearls left, only the empty string and the clasp

that once held it together. And those would be tossed away, as useless.

Saryon and I were pottering about

his flat late that night, putting on the teakettle, an act which always

reminded him—so he was telling me—of another time when he’d picked up a

teakettle and it wasn’t a teakettle. It was Simkin.

We had just finished listening to

the news on the radio. As I said, Saryon had not up until now been particularly

interested in the news of what was happening on Earth, news which he always

felt had little to do with him. But this news appeared, unfortunately, to have

more to do with him than he or anyone else wanted and so he paid attention to it.

The war with Hch’nyv was not

going well. The mysterious aliens, who had appeared so suddenly, with such

deadly intent, had conquered yet another one of our colonies. Refugees,

arriving back on Earth, told terrible tales of the destruction of their colony,

reported innumerable casualties, and stated that the Hch’nyv had no desire to

negotiate. They had, in fact, slain those sent to offer the colony’s surrender.

The objective of the Hch’nyv appeared to be the annihilation and eradication of

every human in the galaxy.

This was somber news. We were

discussing it when I saw Saryon jump, as if he had been startled by some sudden

noise, though I myself heard nothing.

“I must go to the front door,” he

said. “Someone’s there.”

Saryon, who is reading the

manuscript, stops me at this point to tell me, somewhat testily, that I should

break here and elaborate on the story of J or am and Simkin and the Darksword

or no one will understand what is to come.

I reply that if we backtrack and

drag our readers along that old trail with us (a trail most have walked

themselves already!) we would likely lose more than a few along the way. I

assure him that the past will unfold as we go along. I hint gently that I am a

skilled journalist, with some experience in this field. I remind him that he

was fairly well satisfied with the work I’d done on the first three books, and

I beg him to allow me to return to this story.

Being essentially a very humble

man, who finds it overwhelming that his memoirs should be considered so

important that Prince Garald had hired me to record them, Saryon readily

acknowledges my skill in this field and permits me to continue.

“How odd,” Saryon remarked. “I

wonder who is here at this time of

night?

”

I wondered why they did not ring

the doorbell, as any normal visitor would do. I indicated as much.

“They have rung it,” Saryon said

softly.

“In my mind, if not my ears.

Can’t you hear

it?”

I could not, but this was not

surprising. Having lived most of his life in Thimhallan, he was far more

attuned to the mysteries of its magicks than I, who had been only five when

Saryon rescued me, an orphan, from the abandoned Font.

Saryon had just lit the flame

beneath the teakettle, preparatory to heating water for a bedtime tisane which

we both enjoyed and which he insisted on making for me. He turned from the

kettle tostare at the door and, like so many of us, instead of going

immediately to answer it or to look through the window to see who was there, he

stood in the kitchen in his nightshirt and slippers and wondered again aloud.

“Who could

be

wanting

to see me at this time of night?”

Hope’s wings caused his heart to

flutter. His face flushed with anticipation. I, who had served him so long,

knew exactly what he was thinking.

Many years ago (twenty years ago,

to be precise, although I doubt if he himself had any concept of the passage of

so much time), Saryon had said good-bye to two people he loved. He had neither

seen nor heard from those two in all this time. He had no reason to think that

he should ever hear from them again, except that Joram had promised, when they

parted, that when his son was of age, he should send that son to Saryon.

Now, whenever the doorbell rang

or the knocker knocked, Saryon envisioned Joram’s son standing on the

doorstoop. Saryon pictured that child with his father’s long, curling black

hair, but lacking, hopefully, his father’s red-black inner fire.

The psychic demand for Saryon to

go to the front door came again, this time with such a forceful intensity and

impatience that I myself was aware of it—a startling sensation for me. Had the

doorbell in fact been sounding, I could envision the person leaning on the

button. There were lights on in the kitchen, which could be seen from the

street, and whoever was out there, mentally issuing us commands, knew that

Saryon and I were home.

Jolted out of his reverie by the

second command, Saryon shouted, “I’m coming,” which statement had no hope of

being heard through the thick door that led from the kitchen.

Retiring to his bedroom, he

grabbed his flannel

robe,

put it on over his

nightshirt. I was still dressed, having never developed a liking for

nightshirts. He walked hastily back through the kitchen, where I joined him. We

went from there through the living room and out of the living room into the

small entryway. He turned on the outside light, only to discover that it didn’t

work.

“The bulb must have burned out,”

he said, irritated. “Turn on the hall light.”

I flipped the switch. It did not

work either.

Strange, that both bulbs should

have chosen this time to burn out.

“I don’t like this, Master,” I

signed, even as Saryon was unlocking the door, preparing to open it.

I had tried many times to

convince Saryon that, in this dangerous world, there might be those who would

do him harm, who would break into his house, rob and beat him, perhaps even

murder him. Thimhallan may have had its faults, but such sordid crimes were

unknown to its inhabitants, who feared centaurs and giants, dragons and faeries

and peasant revolts, not hoodlums and thugs and serial killers.

“Look through the peephole,” I

admonished.

“Nonsense,” Saryon returned. “It

must be Joram’s child. And how could I see him through the peephole in the

dark?”

Picturing a baby in a basket on

our doorstoop (he had, as I said, only the vaguest notion of time), Saryon

flung open the door.

We did not find a baby. What we

saw was a shadow darker than night standing on the doorstoop, blotting out the

lights of our neighbors, blotting out the light of the stars.

The shadow coalesced into a

person dressed in black robes, who wore a black cowl pulled up over the head.

All I could see of the person by the feeble light reflected from the kitchen

far behind me were two white hands, folded correctly in front of the black

robes, and two eyes, glittering.

Saryon recoiled. He pressed his

hand over his heart, which had stopped fluttering, very nearly stopped

altogether. Fearful memories leapt out of the darkness brought on us by the

black-clothed figure. The fearful memories jumped on the catalyst.

“Duuk-tsarith!”

he cried through trembling lips.

Duuk-tsarith,

the

dreaded Enforcers of the world of Thimhallan.

On our first coming—under

duress—to this new world, where magic was diluted, the

Duuk-tsarith

had

lost almost all of their magical power. We had heard vague rumors to the effect

that, over the past twenty years, they had found the means to regain what had

been lost. Whether or not this was true, the

Duuk-tsarith

had lost none

of their ability to terrify.

Saryon fell back into the

entryway. He stumbled into me and, so I vaguely recollect, put his arm out as

though he would protect me. Me! Who was supposed to protect him!

He pressed me back against the

wall of the small entryway, leaving the door standing wide open, with no

thought of slamming it in the visitor’s face, with no thought of denying this

dread visitor entry. This was one who would not be denied. I knew that as well

as Saryon, and though I did make an attempt to put my own body in front of that

of the middle-aged catalyst, I had no thought of doing battle.