Legends and Lore of the Mississippi Golden Gulf Coast (15 page)

Read Legends and Lore of the Mississippi Golden Gulf Coast Online

Authors: Edmond Boudreaux Jr.

Marathon swimmers would swim the ten-mile course from Biloxi to the Isle of Caprice in the 1920s.

Courtesy of Alan Santa Cruz Collection

.

The next day, Higgins began looking for owners Skeet Hunt and Arbeau Caillavet and, in short order, located Caillavet. Higgins asked why the Isle of Caprice was not listed on any chart. Caillavet explained that they changed the name because Dog Island was not a proper name for a resort and that was the reason it was not listed on the charts. He told Higgins the area was a popular fishing ground for trout, Spanish mackerel and red fish. Caillavet indicated that the island was stable and had weathered many storms with little or no change. Due to the steady wind, the island also had no mosquitoes. Caillavet continued that additional attractions and rental cottages would be built by next year. They hoped to develop it into a famous resort, like many European watering places. Long-term development would include building a seawall around the island and filling it in. Caillavet said, “Then it can really be made into a beautiful and permanent a resort as Deauville or Monte Carlo or Biarritz.” Once again, Higgins questioned the sale of liquor, and Caillavet responded that no liquor would be sold. Caillavet indicated Skeet Hunt and Caillavet himself leased the land to the concessions and casino. The casino was operated by Al Haupt of Natchez, Walter Brenham of New Orleans and Mr. Gregory of Cincinnati, and it was reported to take in about $1,000 a night on weekends. Even though Higgins was unable to obtain liquor during his visit, by all accounts, liquor could be purchased on the Isle of Caprice.

People swimming the Gulf of Mexico surf.

Courtesy of Alan Santa Cruz Collection

.

The Hurricane of September 1926 did little or no damage to most coastal towns, but it did erode a portion of the Isle of Caprice. In 1927, a one-hundred-foot double-deck boat was purchased and rechristened the

Nonpareil

to carry individuals to the island paradise. One of the promotional events of Caillavet and Hunt's Isle of Caprice Company was its annual marathon swim. The starting point was a pier that today is the Beau Rivage Casino property to the Isle of Caprice. The swimmers were each followed by a skiff, and no one was ever injured. In January 1928,

Way Down South Magazine

reported that Biloxi businessmen had built “sports city” on the Isle of Caprice. In its January 11, 1929 issue, the

Guide

, put out by the Mississippi Coast Hotel Association, reported that the Isle of Caprice Company was beginning its schedule of boat sightseeing trips, which included trips to the islands, the scenic rivers, the bays and the picturesque fisheries. Then, on June 9, 1929, the Gulfport Business and Professional Women's Club went to the Isle of Caprice onboard the

Pan American

, and on July 5, 1929, five hundred Memphis Shriners went to the Isle of Caprice. Even a noted actress, Miss Ethel Barrymore, visited the island on April 17, 1931. Buena Vista Hotel manager Fred Moser accompanied Miss Barrymore on the boat trip to the Isle of Caprice, where she enjoyed a day of swimming, dining and sightseeing.

New Orleans Item

reporter Don H. Higgins described the resort island in July 1926, and by 1927, a Chicago journalist had also written an article. Even the University of California allowed its Kappa Beta Sorority to vacation there. By 1927, there were four excursion boats providing transportation between Biloxi and the Isle of Caprice resort. The next few years witnessed seasonal invasions by college students, tourists and area locals. There were family picnics, swimming, beauty contests and fishing along the island's beautiful shores. Of course, visitors also dined, danced and gambled the days and nights away in the casino.

Unnoticed by the visitors was the fact that seasonal storms were eroding the eastern tip of the island. Another problem was the removal of sea oats from the sand dunes. In the beginning, only small amounts of the sea oats were removed. As their popularity increased, the sea oats were used in floral arrangements and even painted in a variety of colors. They became commercially harvested, with Marshal Field of Chicago being one of the largest outlets. Soon the Isle of Caprice's roughly 150 acres of sea oats were gone. The harvesters had removed even the roots, leaving the now unprotected sands dunes to be blown by the Gulf winds.

By 1930, the island was nothing more than abandoned buildings on a sandbar without dunes. In January 1931, large flames could be seen from the mainland on the Isle of Caprice. Some young men from New Orleans were camping on the island, and by accident or vandalismâwe will never knowâthe main building was on fire. Soon the fire spread to other buildings, leaving only the power plant, the artesian well and just a few cabanas. With our nation entering into the Depression years and the Isle of Caprice slipping under water, all ventures and hopes were placed on hold. By the summer of 1932, the island was completely under water. In due time, only the artesian well pipe stood above the water, still gushing fresh water from its deep well. Descendants of Skeet Hunt continued to pay property taxes in hopes that the island would rise again.

For many years, local fishermen would stop and take a drink from this last visible piece of the Isle of Caprice. In time, the pipe rusted and was repaired by some local fishermen. By the late 1960s, it too finally disappeared beneath the waves.

Seventy-eight years have passed since the Isle of Caprice first disappeared beneath the waves, but the old Indian legend of the Isle of Caprice rising from the depths remains. Is it just a legend? Only time will tell.

CHAPTER 23

T

HE

S

HIP

I

SLAND

L

IGHTHOUSES

The history of Ship Island's lighthouses began on March 13, 1848. Louisiana governor Isaac Johnson signed a resolution requesting Louisiana's senators and representative in Congress to try to appropriate a lighthouse for Ship Island. Congress approved the Ship Island Lighthouse and appropriated $12,000 for its construction. At this time, Ship Island was still a major anchorage for ships.

On August 31, 1852, President Millard Fillmore signed into law $12,000 for the Ship Island Lighthouse. In September of the same year, three bids were opened, and John McCaughan of Mississippi won the bid for $8,000. In short order, McCaughan's construction crew was hard at work, and the lighthouse was completed on March 17, 1853. The round brick lighthouse was forty-five feet high, with three windows.

In late November, the light was tested, and on December 25, 1853, Edward Havens was appointed lighthouse keeper, with a salary of $500 a year. In April 1854, Edward and his wife, Mary Mercier Ladnier, were joined by assistant lighthouse keeper Christian Ladnier, brother of Mary Mercier Ladnier Havens and son of Jean Baptiste and Marie Morin Ladnier. Christian's salary was $300 a year.

In June 1855, an accident resulted in the deaths of Edward Havens and Christian Ladnier on Ship Island. Mary Havens was appointed to replace her husband as keeper, and John Reid was appointed assistant. Interestingly enough, John Ried married Edward and Mary Havens's daughter, Adelle Adeline Havens, on July 4, 1850. They had two children, John and Alexander. In November 1856, Mary passed away on Ship Island, and John Ried became lighthouse keeper. William Stanley was appointed assistant to Reid.

The Ship Island Lighthouse and lighthouse keeper's home on Ship Island, 1896.

Courtesy of Maritime & Seafood Industry Museum

.

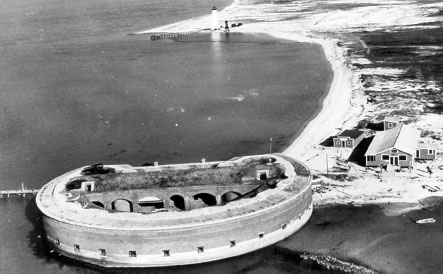

The Ship Island Lighthouse is visible in the background of Fort Massachusetts.

Courtesy of Alan Santa Cruz Collection

.

On February 28, 1859, at twenty-nine years of age, John Reid passed away on Ship Island. In a span of four years, his wife, Adelle Havens Reid, lost her father, uncle, mother and husband. Adelle left the island and moved to Mobile, where she passed away in 1880.

On April 12, 1861, the Civil War began and would last until April 9, 1865. Confederate troops took control of Ship Island and all its structures on January 13, 1861. On September 17, 1861, the island was retaken by Union forces and used as headquarters for the Union Naval Gulf Blockade forces. There was some indication that the lens from the lighthouse was removed by Confederate forces and taken to New Orleans. After the war, reports indicate that the lens, lamps and other accessories were found on Ship Island. In 1862, repairs were made, and in late November, the light was back in service.

Frederic Shede was appointed keeper, and his assistant was Peter Richter. Between 1863 and 1877, several keepers were appointed and removed. One of these was Ordnance Sergeant James McCabe. A report indicated that Sergeant McCabe was not giving “proper attention to his duties.” His assistant was Daniel “Dan” McColl, who had been appointed in February 1875. On May 23, 1877, McColl relieved McCabe as keeper. Dan and his wife, Elizabeth Dudley, served as keepers from 1877 to June 1904, when he passed away on Cat Island. Dan was considered a very colorful person. He had lost his leg in an 1869 railroad accident, but his peg leg did not stop him from climbing and tending the Ship Island lighthouse. Tourists to the island would constantly make remarks about Dan's collection of tokens from all over the world.

Beginning in 1853, it was noted that the beach around the lighthouse was eroding, and by 1885, the lighthouse was in danger of falling. A decision was made to build a new tower and keeper house on higher ground. A location 320 feet south of the old lighthouse was selected. The dunes in this area were fifteen to twenty feet high and would offer some protection. It was estimated that it would take thirty years for the eroding beach to endanger the new lighthouse.

On May 1, 1886, the bid was awarded to John H. Gardner of New Orleans. Gardner proposed building the keeper house for $3,500 and the lighthouse tower for $2,375. The tower was a square metal skeleton with an enclosed lamp room on top. On September 1, 1886, the new light was put into service. In December, it was decided to enclose the whole tower. Weatherboarding was placed on the exterior and sheathing on the interior. A door, windows and shelving were installed and the exterior painted white. This was the lighthouse that most remember.

In 1899, Dan McColl was transferred to the Cat Island Lighthouse, and Peter Clarisse took over the Ship Island Lighthouse. By 1901, the original brick lighthouse had been toppled by the Mississippi Sound. The Ship Island Lighthouse continued to be manned until 1947, when it was automated. The Ship Island Lighthouse was removed from service in the mid-1950s. In 1959, Philip Duvic was granted use of the lighthouse for recreational purposes. A kitchen and bathroom were installed. In addition, a dormitory was set up on the third floor for men and on the second floor for women.

On August 17, 1969, Hurricane Camille struck the Mississippi Gulf Coast and split Ship Island into two sections. The Ship Island Lighthouse had survived numerous previous storms, and it survived Camille as well. With the coast recovering from Camille, repairs on the lighthouse would have to wait.

On June 27, 1972, a fire was reported on Ship Island, and it was discovered that vandals had set the lighthouse on fire. Before long, the wood was ash and the metal blackened on the eighty-six-year-old landmark.