Lenin: A Revolutionary Life (28 page)

Plate 7

Lenin in a wheelchair, 1923 © Bettmann/CORBIS

Plate 8

Crowd at Lenin’s funeral, 1924. The cult begins © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

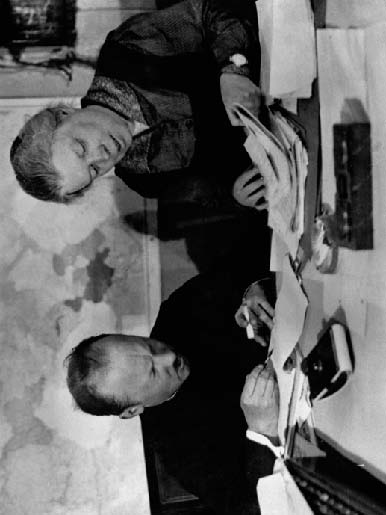

Plate

9

Lenin’s work goes on –

Pravda

editors at work (Bukharin and Maria Ulyanova, Lenin’s sister), 1925

© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

the assumption of civil war. Indeed, he even went so far as to remind Party colleagues that, in the event of a soviet takeover and a refusal of peace by the enemy (something that was as certain as anything could be in politics), then the Bolsheviks would become real defensists, they would ‘be the

war party par excellence

’. [SW 2 368]

This was actually consistent with all Lenin had said on the issue, including

The April Theses

. However, it was not part of the general per

ception of the party of peace on the part of the masses. Even some of the leaders were still surprised by it. Only perceptive observers really understood longer-term Bolshevik aims. According to the diarist Sukhanov ‘We [the Menshevik-Internationalists] were divided [from the Bolsheviks] not so much by slogans as by a profoundly different conception of their inner meaning. The Bolsheviks reserved that meaning for the use of the leadership and did not carry it to the masses.’

7

However, Lenin asserted several times that the majority of the country now supported the Bolsheviks. His critics, including Kamenev and Zinoviev, were more sober in suggesting the Bolsheviks might attain a quarter to a third of Constituent Assembly votes rather than a majority. Second, Lenin argued that a full-scale insurrection was going on in the country. Here he was on surer ground. As we have seen, the Kornilov revolt had galvanized the left into more active defence of its ‘gains of February’ as they became known. The Kornilov affair had raised the spectre of counter-revolution; so, for the masses, it was now or never. Peasants speeded up the acquisition of landowners’ land. Workers fought to control their factories and keep them running. Soldiers and sailors reasserted the authority of their committees and were more determined than ever not to be pawns in an imperialist struggle. Linked to this, Lenin also argued that the enemies of the revolution were wavering. Kornilov had split the propertied classes and provoked the backlash just mentioned. The arrest of Kornilov, and the ensuing despair of the army officers, was sowing confusion among the former elites. Lenin believed the international conjuncture was also right and Bolshevik action was imperative to realize the international potential of the revolution. On 29 September (OS) he argued the world revolution was reaching its ‘third stage’ which ‘may be called the eve of revolution’. [SW 2 371] Lenin insisted on it many times in the campaign of September–October. For instance, he referred to the German mutinies in the Central Committee resolution of 10 October (OS). All the above arose out of his earlier writings. However, as we have seen, one major additional argument began to take a more and more prominent part in Lenin’s armoury, the rather fanciful but powerfully argued notion that only a soviet seizure of power would

prevent

social and economic catastrophe.

Incidentally, the last of Lenin’s communications to his comrades in the Central Committee written on 24 October (OS), which was never sent because he broke cover himself and went to join them, stated that power should be taken by the ‘armed people’ and ‘the masses’. Strangely, nowhere in it does he specifically mention workers. For the last time before the actual revolution, Lenin’s populist matrix emerged from under the orthodox Marxist surface.

Lenin took no direct part in the seizure of power itself before the night of 24–25 October (OS). The overthrow of the remnants of the Provisional Government was not conducted by the Party as much as by the Petrograd Soviet and its Military Revolutionary Committee with Bolsheviks such as Trotsky but also others including Left SRs, anarchists and Left Mensheviks taking a leading role. However, some have suggested that Lenin’s dramatic emergence from hiding was decisive in tipping the balance from a defensive operation to protect the Congress of Soviets which was about to meet and also, perhaps, the city of Petrograd itself which, it was widely though probably incorrectly believed, was on the point of being surrendered to the Germans. We do not know for sure what Lenin did in the vital hours following his arrival at the Smolny Institute, the soviet nerve centre. We do know that he left hiding almost on an impulse and, still in disguise, made his way through the city, narrowly avoiding a Provisional Government patrol. On arrival at the Smolny Institute he handed his disguise to his friend Bonch-Bruevich who had accompanied him. Knowing his retreat might yet be as rapid as his advance, Bonch-Bruevich, only half-jokingly, said he would keep hold of it as it might yet come in handy.

Whether the influence came from Lenin or not, a bolder set of actions emanated from the Smolny in the middle of the night of 24–25 October (OS). The following morning at 10 a.m. the overthrow of the Provisional Government and the establishment of a Soviet Government was proclaimed. Even so, it was only the following evening that, without any significant part being played by Lenin, the Winter Palace was raided and the remaining Provisional Government ministers arrested.

Kerensky himself had already left the city to seek assistance. Later in the day, that is 26 October (OS), Lenin went to the Second Congress of Soviets and was acclaimed as the leader of the Revolution. He was nominated as Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, that is as head of the new government, though for the moment the full personnel of the government were not named as negotiations were continuing. Lenin introduced Decrees on Peace and Land which were approved. The Menshevik and SR leaders, the chief rivals of the Bolsheviks, suicidally walked out of the Congress into what Trotsky described as ‘the dustbin of history’. Lenin, in the midst of these events, commented to Trotsky that ‘The transition from illegality and being hounded from pillar to post to power is too abrupt. It makes one dizzy.’ [Weber 141] It was a dizziness Lenin would have to get used to.

FROM CLASSROOM T

O LABORATORY – EARLY EXPERIMENTS

Almost from the very first day of the October Revolution Lenin’s hopes and expectations for it began to collapse. His opponents had predicted as much. Lenin’s assertion that the transition to soviet power would be ‘gradual, peaceful and smooth’ was so far off the mark that observers have wondered if he seriously meant it or if it was simply a propaganda device. In October, the Bolsheviks had appeared to offer, as far as the population was concerned, four things above all. They were: soviet power; peace; bread (i.e. economic and material security); and land. The delivery of these promises was faltering at best. At the same time the Bolsheviks were gradually improving the toehold on power they had achieved in October. October was no more than a beginning from which more secure consolidation had to be achieved. Opposition also gained momentum but was divided between the anti-Bolshevik soviet left and the more broadly counter-revolutionary propertied classes of the centre and right. Social and economic disruption deepened at an alarming rate. The war against Germany did not disappear overnight. The essential condition for success – world revolution – showed little sign of appearing quickly.

Such was the unpromising situation into which Lenin stepped on 25 October (OS). Up to that time he had been mainly a professor and teacher of revolution, a frequenter of Europe’s great libraries, who con

stantly produced articles of analysis and denunciation. Even in the crucial weeks and months before the October Revolution Lenin had been in hiding and his weapons continued to be words not deeds. Events over which he had no control, like the Kornilov affair, had propelled him into power. In no sense had Lenin, up to this point, exerted leadership over the revolution. As we have seen, he had found it hard enough to exert his authority over the tiny band of ardent supporters in the various higher committees of his own party. With what success would he make the transition to practical politician, to activist? He was stepping out of his professorial classroom and study into a laboratory where actions were judged by their results. But it was no ordinary laboratory. It was chaotic, near-bankrupt and threatened with external attack. Experiments conducted in these conditions would be risky in the extreme and the odds would be strongly stacked against them working successfully. It is hardly surprising that it took Lenin several attempts to get the formula right – at least to his own satisfaction. Maybe even the final formula he bequeathed to his party and people – the New Economic Policy – was flawed in ways that only came to light after his death. The remainder of our study of his life will centre on how Lenin coped with the immense challenges he, and the Revolution, faced.

INITIAL CONSOLIDATION AND THE FIRST CIVIL WAR

Whose power?

In Lenin’s own words in

The Dual Power

of 9 April 1917, ‘the basic question of any revolution is state power.’ [SW 2 18] The first task was to secure power. But there was an associated problem. Whose power was it that would be consolidated? The slogans of October were unambiguous. They all proclaimed ‘All Power to the Soviets’. Lenin, however, had secretly been urging Bolshevik power. Only one of these positions could be implemented.

On the surface, soviet power appeared to reign supreme. It was to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets that the Petrograd Soviet and its Military Revolutionary Committee, which had actually spearheaded the takeover, turned to formalize the new system. The government called itself the Soviet Government and retained the title until 1991. It was through soviets and especially their military revolutionary committees that power began to spread throughout the country in its so-called triumphal march. If the local soviet supported the takeover all well and good. However, where Mensheviks and SRs were in the majority, many soviets did not support the new authorities and this included some major army soviets at the front and in the Ukraine. Here tactics were cruder. Local Bolsheviks, plus a minority of non-Bolsheviks from other parties, set themselves up as a military revolutionary committee and used their authority to call on revolutionary regiments to coerce the soviet majority into acquiescence. In other places the soviet forces as a whole were not strong enough to prevail immediately. In Moscow, the left–right balance was much more even and it took six days of fighting before the authority of the soviet prevailed. The fighting was also notable because, hearing reports of damage to the Kremlin, Anatoly Lunacharsky briefly resigned as Minister of Education. Arresting the remnants of the General Staff at

Stavka

(HQ) in Mogilev was a delicate enterprise. The acting Chief of Staff, Admiral Dukhonin, negotiated an uneasy handover but the troops sent by the Bolsheviks could not resist the temptation of revenge and lynched him before they could be reined in.

The military squads used in such operations gradually became the core of the Bolshevik enforcement system on which it relied from its first days. Spontaneous organizations of the people – ironically those closest to the militia pattern supposedly supported by Lenin, such as Red Guards – were disbanded in favour of more tightly controlled groups. The most famous was the Latvian Rifle Regiment, members of which became Lenin’s and the Soviet government’s bodyguards. They also formed the active arm of the king of all enforcement agencies, the Cheka, when it was set up in December 1917. It is worth pausing here for a moment to reflect, since this was one of the earliest examples of an extraordinary process that affected the whole revolution very quickly. In his writings of only a few weeks earlier, Lenin had insisted on the value of actively democratic ways of conducting state business, or more correctly, what was formerly state business since the state was, in Lenin’s words taken from Marx, to be smashed. Far from being smashed and replaced by militias and socially conscious workers in place of civil servants, the new institutions increasingly took on a traditional look. Some issues, like the restoration of ranks and insignia, not to mention the death penalty, in the Red Army, eventually caused Party scandals. Others, particularly in the early days, were passed over without even being noticed. By the time Lenin came to reflect on what was happening he was, as we shall see, already complaining about drowning in a sea of red tape. Lenin was finding out that while one might have ideas about how a completed revolution would look, the exercise of transition – what steps one took the day after the revolution, the day after that and so on – was much trickier than anticipated. No natural instinct to build the revolution emerged from the masses. The new leaders were too preoccupied with facing a massive wave of events to do more than respond instinctively. By the time they came to take stock they were already well off course and it was not clear that, with the prevailing winds and tides, they would ever be able to regain their expected destination.

Despite the operation against

Stavka

, the main figures in the General Staff, including Kornilov who slipped out of jail, along with other parts of the officer corps and a crystallizing resistance to soviet power, had retreated to the protection of Ataman Kaledin, chief of the Don Cossacks. South Russia and parts of eastern Ukraine became no-go areas for soviet power and General Alexeev formed the anti-soviet Volunteer Army. The remainder of Ukraine was drifting towards independence. Siberia had areas of support for each of the two sides and was of uncertain affiliation for some time to come. However, the Soviet government, with its increasingly effective Red Army also growing from politically active Bolshevik regiments and their allies, appeared, by the beginning of the new year, to be dealing a series of powerful blows to the havens of counter-revolution. In January radical Don Cossacks repudiated the authority of Kaledin. In early February Kiev fell to soviet forces. By the end of February, Rostov and NovoCherkassk were under soviet control and the Volunteer Army was forced to retreat to the Kuban. However, the Germans took Kiev on 2 March and threw out the left and restored the nationalist Rada (Assembly). The following day the peace treaty was signed at Brest-Litovsk handing Ukraine and other territories to Germany and Austria-Hungary, and driving soviet authority out. However, on 14 March Red troops took the last stronghold of the Volunteers, the Kuban capital Ekaterinodar. When, a month later (13 April), Kornilov himself was killed during an unsuccessful attempt to retake Ekaterinodar, it appeared that the Civil War was all but over. Many Bolsheviks were of this opinion. Considering also that peace had been made with Germany, it appeared that fighting might soon cease. Nothing could have been further from the truth. But before we turn to the renewal of the Civil War in May, we need to look at many other aspects of the early months.

As a result of the processes traced above, soviet power appeared to be relatively secure by March 1918. However, such an assertion begs a vital question. Was it soviet power that occupied this position or was it Bolshevik power that had triumphed?

While Lenin had wavered over the issue of soviet power in 1917 he never wavered over Bolshevik power. From his first, rhetorical, assertion that the Bolsheviks were prepared to take power uttered at the First Congress of Soviets he proclaimed his resolve. Even when things turned against them in July Lenin still believed in a Bolshevik-led armed uprising in the context of a nationwide revolution – roughly what happened in October. His drive for power in September and October was ambiguous in the early stages with the uncharacteristic musing about compromise and peaceful transfer of power between soviet-based parties. However, the very titles under which his later letters and articles have come down to us – ‘The Bolsheviks Must Assume Power’ and ‘Can the Bolsheviks Retain State Power?’ – tell their own story. At the Central Committee meetings of 10 and 16 October (OS) it was Bolshevik power that Lenin urged.

Lenin’s imagination had also, in professorial mode again, been fired by the example of the Jacobins in the French Revolution. This association of ideas is a key to unlocking the seemingly utopian and disparate parts of Lenin’s discourse on the revolution in the weeks leading up to October. The Jacobins had inherited a crumbling revolution, threatened by impending foreign invasion, from the temporizing Girondins. Through resolute revolutionary action, including terror and sending out plenipotentiaries (

représentatives en mission

) from the centre, they had turned the situation round. Lenin believed he and the Bolsheviks could do the same, the hapless Menshevik and SR right playing the role of Girondins. As far back as July Lenin had defended the Jacobin heritage. The theme grew as the October Revolution approached. It was their example which inspired some of the more improbable statements which we have seen that he made at the time, notably that only further revolution could defend the left and create a transition that would be ‘gradual, peaceful and smooth’ [SW 2 261]; that the ‘resources, both spiritual and material, for a truly revolutionary war are still immense’ [SW 2 368]; that ‘the workers and peasants would soon learn’ [SW 2 261] and ‘will deal better than the officials … with the difficult practical problems’ of production and distribution of grain [CW 24 52–3 (April)]; and that the Bolsheviks, like the Jacobins, would become ‘the war party

par excel

lence

’. [SW 2 368] Lenin increasingly appealed to ‘the history of all revolutions’, meaning primarily the French. [SW 2 450] He even quoted Marx who was himself quoting one of the Jacobin leaders, Danton: ‘Marx summed up the lessons of all revolutions in respect to armed uprising in the words of “Danton the greatest master of French revolutionary policy yet known:

de l’audace, de l’audace, encore de l’audace

”’ (boldness, boldness and yet more boldness). [SW 2 427]

Lenin’s letter of the night of 24 October (OS) claimed power would be handed over to ‘the true representatives of the people’ and ‘not in opposition to the Soviets but on their behalf’ as ‘proved by the history of all revolutions’. [SW 2 449–50] The official declaration of 25 October (OS), issued by the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC), claimed power passed to itself, the MRC, and thereby ‘the establishment of Soviet power …. has been secured.’

1

[SW 2 451]

The coup was presented to the Second Congress of Soviets in the wrapping of soviet power but the realities were changing. The most formidable of opponents, from the soviet right to Martov on the internationalist left, walked out and formed the never-effective Committee for the Salvation of Russia. That left the entire Congress with virtually no alternative leadership to the Bolsheviks. Many delegates were Bolsheviks and a majority appear to have been mandated to support soviet power before they left their home areas, that is

before

the Bolshevik operation. 612 out of a total of 670 delegates were mandated to end the alliance with the bourgeoisie and only 55 to continue it. Holding to their mandate the majority supported the Bolsheviks and many, but by no means all, declared themselves to be ‘Bolshevik’, around 390 being the accepted figure.

2

However, there is some difficulty in identifying just what being a Bolshevik meant. Many identified with the Bolsheviks mainly, probably only, because the Bolsheviks supported soviet power. Therefore, more or less by definition, most of those who supported soviet power described themselves as Bolsheviks. It is extremely unlikely that many of them had a developed sense of what the Bolsheviks stood for beyond their immediate slogans.

Many Party leaders, including Kamenev and Zinoviev, had been sceptical about the Bolsheviks taking power alone, hence their ‘strikebreaking’ outburst. But even after 25 October (OS) some Party leaders believed the emerging path of unsupported Bolshevik power was not only impossible, it was undesirable and could lead to unhealthy dictatorship. An alliance of soviet parties would, they believed, be more democratic. On 4 November (OS) they expressed themselves unambiguously: ‘It is our view that a socialist government should be formed from all parties in the soviet … We believe that, apart from this, there is only one other path: the retention of a purely Bolshevik government by means of political terror.’ To follow this path would result in cutting the leadership off from the masses and ‘the establishment of an unaccountable regime and the destruction of the revolution and the country’.

3

Amazingly Kamenev and Zinoviev, who had not been expelled as Lenin had demanded, were prepared to criticize again.