Leviathan

Authors: John Birmingham

John Birmingham tells stories for a living. For doing so he has been paid by the

Sydney Morning Herald

, the

Age

, the

Australian

,

Penthouse

,

Playboy

,

Rolling Stone

,

HQ

,

Inside Sport

and the

Independent Monthly

. He has also been published, but not paid, by the

Long Bay Prison News

. Some of his stories have won prizes including the George Munster prize for Freelance Story of the Year and the Carlton United Sports Writing Prize.

Leviathan

, John's fifth book, was first published in Knopf hardback in 1999. His earlier works are

He Died With a Felafel in His Hand

(now being made into a feature film starring Noah Taylor),

The Tasmanian Babes Fiasco

,

How to be a Man

and

The Search for Savage Henry

. He lives at the beach with his wife, baby daughter and two cats. He is not looking for any more flatmates.

He Died with a Felafel in His Hand

The Tasmanian Babes Fiasco

How to be a Man

(with Dirk Finthart)

The Search for Savage Henry

(as Commander Harrison Biscuit)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian

Copyright Act 1968

), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Leviathan: The Unauthorised Biography

ePub ISBN 9781742741628

A Vintage Book

Published by Random House Australia Pty Ltd

Level 3, 100 Pacific Highway, North Sydney, NSW 2060

http://www.randomhouse.com.au

First published in Knopf hardback in 1999

This Vintage edition first published in 2000

Copyright John Birmingham 2000

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian Copyright Act 1968), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia.

Addresses for companies within the Random House Group can be found at

www.randomhouse.com.au/offices

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry

Birmingham, John, 1964-.

Leviathan: the unauthorised biography of Sydney.

Rev ed.

Bibliography.

Includes index.

ISBN 978 0 091 84203 1 (pbk.).

1. Cities and Towns - New South Wales - Sydney - Growth. 2. Immigrants - New South Wales - Sydney. 3. Aborigines, Australian - New South Wales - Sydney - History. 4. Police - New South Wales - Sydney. 5. Crime - New South Wales - Sydney. 6. Sydney (N.S.W.) - History. 7. Sydney (N.S.W.) - Environmental conditions. 8. Sydney (N.S.W.) - Social life and customs. I. Title.

994.41

Extracts from

Green Bans, Red Unions

by Meredith and Verity Burgmann reproduced with kind permission of UNSW Press. Extracts from

Weevils in the

Flour

by Wendy Lowenstein reproduced with kind permission of the author.

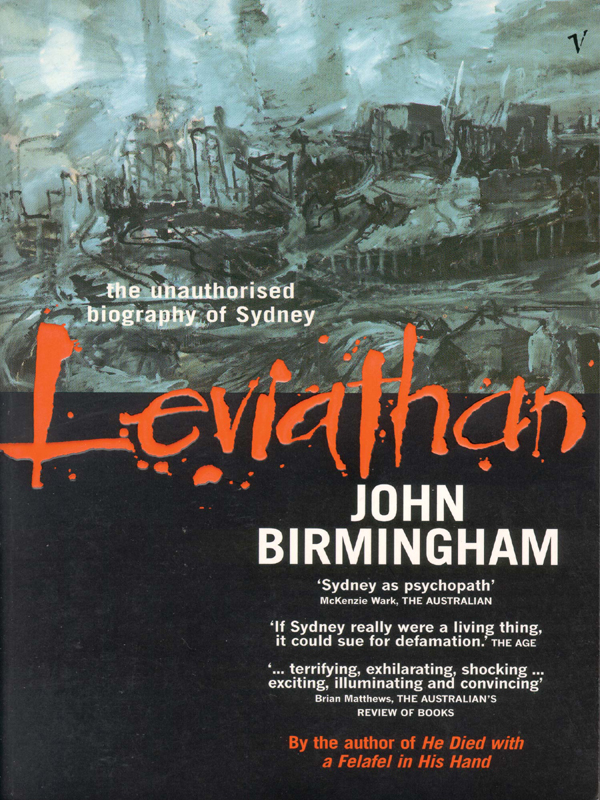

Cover painting by Kevin Connor

Cover design by Greendot Design

In memory of Pat Bell.

Drinker, smoker, talker, friend.

A great loss to the city.

A lot of innocent people suffered to make this book happen. I owe them all thanks, beers and a friendly squeeze on the rump. In a mate-to-mate sort of way, you understand. So present tooshies â¦

Annette Hughes for all sorts of nifty bayonet work in the trenches; Caitlin Lye and Shelly Horton for some sterling efforts on the sick-making microfilm readers at State Library; Andrew Hollis at the Bureau of Meteorology, for his detective work on the weather records; Ross Fitzgerald for casting a gimlet-eyed gaze over the Rum Rebellion section, when my first choice, Grafton Everest, was caught indisposed at the last moment; Ross Pogson and friends at the Australian Museum for help with ⦠uhm, really old stuff; all of the staff at the State Library of NSW, especially the crew at the Mitchell and Dixson, and the gang in the Glasshouse for keeping me thoroughly caffeinated. A jittery salute too, to the boys at Due Mondi for the double, triple and quadro espressos which kept me awake, alert and jittering at warp speed in the Mitchell during a thousand long, long afternoons. And hell, while I'm at it, thanks to everyone at Gusto in Bondi for the brekky rolls and toasted croissants which pushed me into the day in the first place; Neville Wran for enduring half an hour of my ranting questions about the power structure of the city at the end of a very long day; Michelle Jeuken, Les Wales and all the crew at the Macquarie Fields cop shop; Gordon and Wendy Gallagher for taking me into their confidence at the worst possible time; Bronwyn Ridgeway, Rowan Cahill and Bill Langlois for help with the green bans; Liz Wynhausen, Judith Elen and Paul Fraser for delving into the bowels of the News Ltd library; Michael Pawson for smoothing my troubled passage through maritime history; Bryce Wilson, Laltu and Mr Kang for help with the slave cases (which never made it to print thanks to our enlightened defamation laws); Tony Hughes for a champion effort on the photocopiers and for the research papers he knocked out on my behalf; the Monday lunch crew for six hundred chicken curries; the hard chargin' bitches of the Valerie's Surf Club for not cancelling my sorry butt when I had to skip a whole season while on deadline; Dinh Tran and Hiep Chi Phan for enduring my dumb questions with superhuman patience; and Anne-Maree Whitaker for making sure the dead stayed that way.

And two big tooshy squeezes for the following colourful Sydney writing identities for their stand up efforts above and beyond the call of duty. From Random House the fabulous Jane Palfreyman, the awesome Ana Cox and the bodacious Jody Lee. From somewhere in the forest, the spookily perceptive and always three-steps-ahead-of-me Julia Stiles. From the back paddocks of Warwick the long suffering, pants backwards nine hundred bucks richer but wishing he'd never touched my filthy money Peter McAllister. And from just across the brown couch, via two cats and a Jane Austen novel, my amazing wife Jane.

Â

I luvs yooz all.

JB

There Leviathan hugest of living creatures, on the deep stretched like a promontory sleeps or swims, and seems a moving land â¦

John Milton,

Paradise Lost

The Long Goodbye

Make a hole with a gun perpendicular

To the name of this town in a desktop globe

Exit wound in a foreign nation.

Ana Ng, They Might Be Giants

Dinh Tran's city was dying. People ran through the streets, terrified, aimless, spooked by the rumble of distant artillery and the crash of rockets falling nearby. They ran under hot grey skies, unnerved by short bursts of remote gunfire. Some had gone mad. You could see them here and there, mostly frail-looking older men, quiet and trancelike in the midst of the stampede. Dinh picked his way carefully through the crowd, dismounting and pushing his old bicycle through the worst of the chaos, around those few cars and trucks that had been abandoned in the crush, adding to the confusion. A scared, thin young schoolteacher, he was headed, like many, for the port of Saigon. He hoped to find a friend there who might deliver his family to the safety of the American fleet waiting offshore. But Dinh's escape, like the Americans' own, was confounded by the speed and violence of the city's collapse.

He was staying with relatives in the second district, a faded gem of French colonial rule close to the waterfront. His parents had sold most of their property ten days earlier, intending to flee as four divisions from the north, supported by heavy armour and artillery, tripped over a few battered, lightly armed units of what remained of South Vietnam's army at the hamlet of Xuan Loc. The battle for Xuan Loc, the last great engagement of the war, was fought less than seventy kilometres from the Trans' front step, and when the killing was done with, South Vietnam was no more. Dinh and his family had followed the disintegration as best they could. Some omens could be read easily in the closure of local shops and businesses, violent chaos spreading through the streets in defiance of a military curfew, whole families vanishing from the neighbourhood, garbage rotting in the streets, power failures, tracer fire arcing through the night sky, flashes and rumbles over the horizon. Other events only whispered their message, their meanings transmitted through rumour and low-grade intuition â the flight of Vietnamese government figures from the US air base at Tan Son Nhut; mass desertions of armed forces personnel; the machine gunning of fleeing civilians on the river barges; the resignation of President Thieu, his late-night dash to the air base, escorted by American spies toting machine guns and hand grenades, all of them expecting to be pulled over and shot by South Vietnamese troops.

The communists had surrounded Saigon by then. Up to twenty divisions with armoured support. They even had a small air force composed of southern mutineers which bombed the city on the day after the President's escape. The raid touched off wild rumours of a coup, or perhaps the first dread footfall of the North Vietnamese Army within the city itself. But that was one more day away. Even so, Dinh could hear the war getting closer every minute, could feel it through his feet with the explosions of rockets and tank fire in the city precincts, could smell it in the dark oily smoke which boiled up from warehouse fires and intermittent shell bursts. The air in his chest thudded to the beat of evac choppers, while American gunships and navy jets flew shotgun overhead.

âThe soldiers of the Republic had abandoned the army,' said Dinh. âThey had abandoned their arms and uniforms. People were panicking and running around, trying to find a way to escape.' He leant forward as he said this, holding the memory within himself. He seemed to stare into and through the photographs arranged in front of him, dozens of them, spread across two coffee tables, pressed between glass and tabletop, tracing the pilgrimage of the Tran family from Saigon to Sydney; family snaps in refugee camps, tragic 1970s fashions in Villawood, flares and body shirts in front of the first car, the first house in a new country, the first high school dance. A slow but unmistakable accretion of security and wealth. From the photograph of a small, fragile family group standing in the dust of a Malaysian resettlement camp, through to a beaming, healthy new daughter in ski parka and boots up in the Australian Snowy Mountains.

âI used my bicycle to get to the port of Saigon,' Dinh recalled quietly. âOn that day people were moving around everywhere, not knowing where to go or what to do. Just walking and riding. Not much traffic, but people everywhere. On the twenty-ninth there was some bombing. We heard the noise of tanks moving and some gunfighting. There weren't too many people in the heart of Saigon. Very few soldiers. But there were probably a few thousand people running around the port. They just ran around in panic trying to escape. I saw some navy boats in the river, but nobody on them.'

The smell of steamed rice crept in from the kitchen. We sat in Dinh's living room and sipped a sickly sweet fizzy cola while Saigon burned and died behind his eyes. The room was not very big. Apart from a small black lacquer wall-hanging with an opal outline of Vietnam, it contained few signifiers of the cultural shift wrought on Sydney by the Vietnamese who settled there after the war. Escape had been closer that afternoon than Dinh realised. While he noticed only a few small abandoned navy craft at anchor in the river down at the port, around a bend at Khanh Hoi lay two huge barges, tugged there as part of an abortive American effort to move 30 000 high-risk Vietnamese out of the city. The barges were massive, with sandbag redoubts along the sides, harking back to their previous role, ferrying militia forces up the Mekong to Phnom Penh. There was no government presence of any sort at Khanh Hoi the afternoon Dinh went looking for an escape route. Anyone who cared to step onto the barges could have done so unchallenged. They pulled away from the docks, half empty, as evening fell and Dinh's family gathered together in their small room in the second district to await the arrival of the communists.

It was not long in coming. Next morning, NVA General Tran Van Tra ordered his army to advance into Saigon an hour after the last American chopper lifted off the roof of the embassy. It was a disastrous, humiliating exit for the superpower. Thousands of Vietnamese crawling and scrambling over the embassy fence, looting and burning the snack bar and warehouse, letting off small arms, chanting anti-American slogans and driving the embassy vehicles in mad slashing circles on the ruined lawn. Revolt everywhere, except for the local fire brigade who had volunteered to stay and fight the blaze, expecting in vain to be picked up by the Americans.

Â

Totalitarian regimes aren't big on entertainment. Lots of parades and a constant subcutaneous frisson of terror just about covers the options. Thus at nine in the evening of 15 April 1980, when Dinh Tran, his wife Phong and their two daughters stepped out through the door of the small closed-up shop where they'd been living since the communist takeover, they presented a weird picture to the deserted streets of Saigon, or Ho Chi Minh City as it had become. A young, neatly dressed family stepping out on the town where there was nowhere to go and nothing to do. They hailed a passing cyclo, the ubiquitous three-wheeled taxi which had survived the end of the war, and directed the driver to take them to a closed riverside market about twenty kilometres away.

They rode quietly through the mostly deserted streets, an anxious trip of about half an hour, through intersections guarded by sleepy, disinterested policemen. Finally stopping amongst the shuttered market stalls, Dinh paid off the cyclo jockey and ushered his family into the shadows. He was frightened and tense and torn up inside. Just before leaving home he had leaned forward and kissed his frail father's shaking head. âI have to go now, Daddy,' he'd said, squeezing out the words. After Dinh turned his back to leave, he knew he would not see his father again. There was, however, no time for dwelling on such things. Dinh hustled everyone dockside and down to the end of a jetty. A fishing boat lay tethered there, low in the water but otherwise no different to any other in the small fleet bobbing slowly about in the dirty, foul-smelling river. They climbed aboard and â one, two, three, four â they dropped out of sight. The dock was still again; hot, quiet, dark and deserted. It remained so for a short time until an engine started up with a very faint, throaty growl and the little vessel into which the Trans had disappeared slowly pulled away from the dock and out into the river.

It was close and rank down in the boat's hold, pitch black and claustrophobic. Dinh could sense rather than see the press of thirty, maybe forty other bodies in the confined space. Hard to tell in that inky gloom. He kept Phong and the girls nearby, huddled tight, just as he had pressed close to his own parents and siblings on their flight out of North Vietnam twenty-six years earlier. He thought sadly of his father who was simply too old and weak to attempt this sort of adventure again. The other runaways whispered softly as the trawler slipped quietly downstream, stopping now and then to pick up more people who dropped into the hold through the tiny hatch which Dinh saw only as a square of lighter darkness. âIt is like they fall down from the sky,' he thought.

They motored along, stopping and starting, until dawn, by which time there were nearly sixty people below decks. In the cabin above, the crew ran up the government flag to establish their bona fides as honest toilers of the People's Republic. They ploughed on for a few more hours, picked up more human cargo, this time actually dressed like fishermen. Then the engines started to vibrate and roar and everyone in the hold felt the trawler lean back on her heels and pick up speed. They were away. Relief washed through the densely packed band of refugees. The little boat started to pitch and roll as she punched into the swell of the South China Sea.

Dinh relaxed a little; but while he took comfort in the long curling rise of the waves beneath the keel he could not let go completely. This was his third attempt to escape from Vietnam and now, having made the open sea, the most dangerous. Although thousands had made it out of Vietnam, thousands more had died trying. The fast inshore gunboats of the regime were perhaps the least of their worries. If caught they might be sent to a prison camp, a marginal threat when the whole country was effectively a prison anyway. There were other terrors ahead: storms, freak waves, shipwreck, thirst, starvation or madness. The sea might deliver them up to freedom, or into the hands of Thai pirates who would most likely murder them, after indulging in a few hot, slow days of rape and torture. If they avoided all that and made it into international waters, they might be run down by a supertanker. The boat might fall apart. The sea could swallow them up without trace. Or the crew might just get a hundred kilometres offshore and force them all over the side at gunpoint. Although Dinh had helped put this escape network together, he had bitter experience of the mendacity of his fellow man.

His brother had escaped via a secret network some years before. Dinh spoke to the smugglers, who said they could repeat the getaway at the cost of all the family's savings. A tall, well-built Kampuchean picked them up from their house at four in the morning. No baggage, no possessions. Normal street clothes for the long sea journey. They were crammed into a small sclerotic Honda, and driven to a province about 200 kilometres from Saigon. They pulled up to a stall at dawn, a hut beside the road with a very old table and some chairs. An old man ran the store, sixty years of age, thin and very poor. The driver asked them to wait while he picked up some other passengers for the next stage of the journey. He would return in an hour. They waited for three.

âThey abandoned us,' he muttered fiercely, his voice quavering. âThey tricked us. We were nearly captured. We sat there, my wife and my small children and, at the table next to us, two more people. Two other escapees, disguised like poor people, labourers or peasants. Only at the end, as we all became very frightened, did we know the truth. We sat in this hut watching the dirt road out the front, cars and trucks and carts rolling by, until we gave up and returned to Saigon.'

After another unsuccessful attempt Dinh knew he had to organise his own escape network. He approached one of the few people he trusted outside his own family, another teacher at his school, his best friend Cuong. Cuong and Dinh worked hard at being good fanatical comrades during the day. So diligent were they about maintaining their facade that the school's principal, an informer, trusted them implicitly, never imagining that the atlases, encyclopaedias and English language textbooks they gathered were to be used for anything more than school lessons. âThey never thought we would escape,' said Dinh with more than a touch of satisfaction. âDuring the day we worked very hard and contributed everything we could to the school. But outside, at night, we prepared our escape.'

Cuong had many relatives in the fishing industry. They helped the teachers buy a twelve-metre fishing boat with a covered hold and a simple wheelhouse, helped them install the equipment and plan the provisions needed for a sea voyage. Cuong and Dinh pored over the old encyclopaedias after dusk fell, studying the oceans and currents and consulting Cuong's closest relatives for more specific details about the coastal waters. They knew that when they left they would have to sail due east from Saigon, directly into the South China Sea on a heading for the military hot zone of the Spratley Islands. They would never make it there, they hoped. April's prevailing winds and currents should, over the slow beat of many hundreds of nautical miles, drag the little boat and its seventy-three passengers around in a wide arc down towards the joining waters of Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines.

On the evening of the first day the boat hit a sandbank and stuck fast. A terrible shudder ran through the hull as they fetched up on the submerged hazard. Worried murmurs filled the darkened hold as the engines cycled up to no effect. The boat would not move. Finally word came down for all the men aboard to climb over the sides and push the stranded craft off. A bizarre scene ensued as two dozen Vietnamese men, all in their casual street clothes, surrounded by miles of ocean, laboured at the sides of the vessel, while far away on the horizon the lights of the coast shimmered and winked. It took half an hour to work the vessel free.

There was no food on that first day because, apart from the incident on the sandbank, nobody was allowed above decks. They waited until they were several hundred kilometres beyond Vietnam's territorial waters before relaxing the rule. And even then, with so many people squeezed into such a small area, it was not safe to have more than two or three people moving around at any one time. Everyone sat very still for a week and a half, fearful that movement might capsize the boat. Rice was cooked in little petrol burners up on deck and passed from hand to hand below. Foreign ships passing close by made no move to assist them.