Life in a Medieval City (10 page)

Read Life in a Medieval City Online

Authors: Frances Gies,Joseph Gies

Tags: #General, #Juvenile literature, #Castles, #Troyes (France), #Europe, #History, #France, #Troyes, #Courts and Courtiers, #Civilization, #Medieval, #Cities and Towns, #Travel

Small Business

And he looks at the whole town

Filled with many fair people;

The moneychangers’ tables covered with gold and silver

And with coins;

He sees the squares and the streets

Filled with good workmen

Plying their various trades:

One making helmets, one hauberks

,

Another saddles, another shields

,

Another bridles, and another spurs

,

Still another furbishes swords

,

Some full cloth, others dye it

,

Others comb it, others shear it;

Others melt gold and silver

,

Making rich and beautiful things

,

Cups, goblets, écuelles

,

And jewels with enamel inlay

,

Rings, belts, clasps;

One might well believe

That the city held a fair all year round

,

It was full of so many fine things

,

Of pepper, wax and scarlet dye

,

Of black and gray velvet

And of all kinds of merchandise

.

—

CHRÉTIEN DE TROYES I

in

Perceval, le Conte du Graal

A

lmost every craftsman in Troyes is simultaneously a merchant. The typical master craftsman alternately manufactures a product and waits on trade in his small shop, which is also his house. Sometimes he belongs to a guild, although in Troyes only a fraction of the hundred and twenty guilds of Paris

1

are represented. Many crafts stand in no need of protective federation or have too few members to form a guild.

Each shop on the city street is essentially a stall, with a pair of horizontal shutters that open upward and downward, top and bottom. The upper shutter, opening upward, is supported by two posts that convert it into an awning; the lower shutter drops to rest on two short legs and acts as a display counter. At night the shutters are closed and bolted from within. Inside the shop master and apprentice and a male relative or two, or the master’s wife, work at the craft.

In a tailor’s shop, the tailor sits inside, cutting and sewing in clear view of the public, an arrangement that simultaneously permits the customer to inspect the work and the tailor to display his skill. When the buying public arrives—even if it is only a single housewife—tailors, hatmakers, shoemakers and the rest desert their benches and hurry outside, metamorphosing into salesmen who are so aggressive that they must be restrained by guild rules—for example, from addressing a customer who has stopped at a neighbor’s stall.

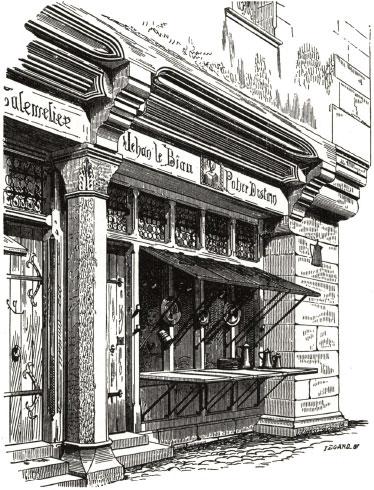

Medieval shop front

, sketched in Brittany by Viollet-le-Duc, nineteenth-century architect. The horizontal shutter was raised when the shop was opened to form an awning over the merchandise.

Related crafts tend to congregate, often giving their name to a street. Crafts also give their names to craftsmen—Thomas le Potier (“Potter”), Richarte le Barbier (“Barber”), Benoît le Peletier (“Skinner”), Henri Taillebois (“Woodman”), Jehan Taille-Fer (“Smith”). With the rise of the towns, surnames are becoming important; the tax collector must be able to draw up a list. But neither in the case of the man nor the street is the name a reliable guide to the occupation. Just as a grocer’s son may be a chandler, so the Street of the Grocers may be populated by leather merchants and shoemakers.

Not far from the helmetmakers, armorers, and sword-makers one may be sure to find the smiths, who not only produce horseshoes and other finished hardware for retail sale, but supply the armorers with their wrought iron and steel. Iron ore is obtained almost entirely from alluvial deposits—“bog iron”—and only rarely by digging. Though coal is mined in England, Scotland, the Saar, Liège, Aix-la-Chapelle, Anjou, and other districts, iron ore is smelted almost exclusively by charcoal. A pit is dug on a windy hilltop, drains inserted to allow the molten iron to be drawn off, and charcoal and ore layered in the hole, which is sealed at the top with earth. The advantage of this method is that the iron drawn off has some carbon in it; in other words, it is steel of a sort. Medieval metallurgists do not really understand how this happens. This “mild steel” is taken in lumps to the smithy.

The blacksmith’s furnace is table-high, with a back and a hood, and like those of the smelters, burns charcoal. The smith’s apprentice plies a pair of leather bellows while the mith turns the glowing bloom with a long pair of tongs. When it is sufficiently heated, the two men drag it out of the furnace to the floor, where they break off a chunk and take it to the anvil, which is mounted on an oak stump. They pound, then return the chunk to the fire, then back to the anvil for more pounding, then back to the fire. Hour after hour the two swing their heavy hammers in rhythmic alternation, their energy slowly converting the intractable metal mass. This metal may vary considerably in character, depending on the accident of carbon-mixing at the smelter.

If the smith is fabricating wire, the next step will be to draw a piece of the hot metal through a hole with pincers. Several such drawings, each time through a smaller hole in a plate, accomplished with patience and much labor, produce a wire of the correct diameter, which is retempered and cut into short lengths. These are sold to the armorer up the street, who pounds them around a bar into links, the basis of chain mail.

The sages believe iron is a derivative of quicksilver (mercury) and brimstone (sulfur). The smith and the armorer know only that the material they get from the smelter sometimes is too soft to make good weapons or good chain mail, in which case they consign it to peaceful uses—plowshares, nails, bolts, wheel rims, cooking utensils. Other craftsmen who use the products of the forge include cutlers, nail makers, pin makers, tinkers, and needlemakers. But the great use of iron, the one that ennobles the crafts of smith and armorer, is for war, either real or tournament-style.

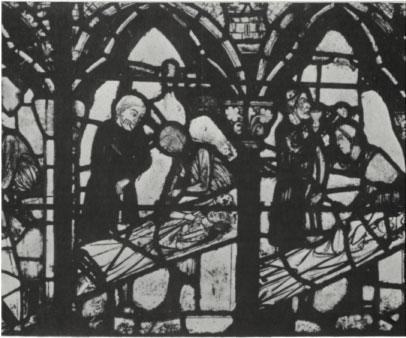

Sculptors at work

, as shown in Chartres Cathedral window. Medieval sculpture, much of high quality, was created by men trained as stonemasons. Often the Master of the Works doubled as sculptor.

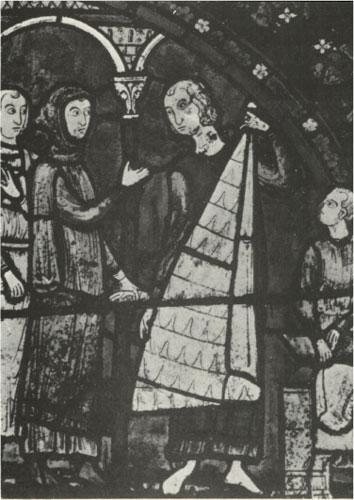

Merchant furriers

. The furrier displays a cloak to a customer, while his apprentice stands behind him ready to hand out additional furs from the stock. The picture is the signature of the St. James window at Chartres, donated by the wealthy furriers’ guild.

There are also metalworkers on a more refined plane: goldsmiths and silversmiths. Since the twelfth century those of Troyes have enjoyed a wide reputation. The beautifully worked decoration of the tomb of Henry the Generous and the silver statue of the same count are justly famous. Goldsmiths are the aristocrats of handicraft, though not all are rich. Some goldsmiths scrape along working alone, making and selling silver ornaments, with hardly a thread of gold to their name. But most have an apprentice and a small store of gold, and fabricate an occasional gold paternoster or silver cup. The most prosperous have well equipped shops with two workbenches, a small furnace, an array of little anvils of varying sizes, a supply of gold, and two or three apprentices. One holds the workpiece on the anvil while the master hammers it to the desired shape and thickness, wielding his small hammer with incredible speed. Gold’s value lies not merely in its rarity and its glitter but in its wonderful malleability. It is said that a goldsmith can reduce gold leaf by hammering to a thickness of one ten-thousandth of an inch. Thin gold leaf embellishes the pages of the illuminated manuscripts over which monks and copyists labor.

Hours of labor, tens of thousands of blows, with the final passage of the hammer effacing the hammer marks themselves—these are the ingredients of goldsmithing, a craft of infinite patience and considerable artistry.

But the bulk of even a prosperous goldsmith’s work is in silver, the second softest metal. Sometimes a smith makes a whole series of identical paternosters or ornaments. To do this he first creates a mold or die of hardwood or copper and transfers the shape and design to successive pieces of silver by hammering. For repair jobs he keeps on hand a quantity of gold and silver wire, made in the same way the blacksmith makes his iron wire.

As the armorer depends on the smith, the shoemaker depends on the tanner, though he prefers to have his shop at a distance from his supplier’s operation. The numerous tanners of Troyes occupy two streets southeast of the church of St.-Jean. Hide-curing, either by tanning or the ancient alternative method of tawing, creates a pungent atmosphere. Masters and apprentices may be seen outdoors, scraping away hair and epidermis from the skins over a “beam” (a horizontal section of treetrunk) with a blunt-edged concave tool. The flesh adhering to the underside is scraped off with a sharp concave blade. Next the hide is softened by rubbing it with cold poultry or pigeon dung, or warm dog dung, then soaked in mildly acid liquid produced by fermenting bran, to wash off the traces of lime left by the dung.