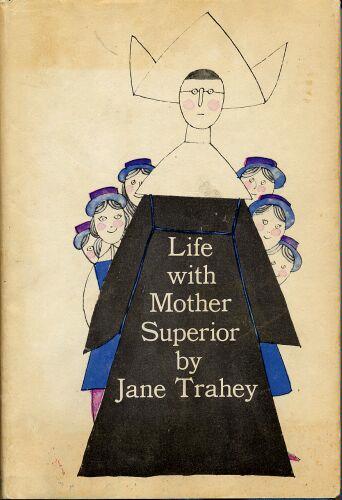

Life With Mother Superior

By Jane Trahey

Foreword

I

was lucky enough to be born a Catholic and fortunate enough to be Irish. What more could anyone ask? Well, my mother asked much more than that. She wanted a charming, polite, intelligent, well-mannered youngest child—instead of the off-beat rebellious child she had.

For the first twelve years of my life, she tried, unsuccessfully, to produce the results desired; then disillusioned and tired, she turned me over to the academy, which she firmly believed would and could polish her treasured piece

of

carbon and produce to order on Graduation Day one sparkling diamond.

The nuns I knew certainly deserved “A” for effort, considering what they had to work with—and what I found fun and amusing to write about my days at St. Marks and

Life with Mother Superior

perhaps concerns itself more with the frosting than the cake. My impressions of the life were the first light shed on the fine art of living, and if I could live it over again, I wouldn’t change a minute of it.

Chapter One: Bad Day for Black Sock

The only difference between the school Mama picked out for me and The Girls’ Reformatory was tuition. Mama paid for me instead of having me committed. Other than that, the rules, the hours, and the food were just about the same. I had no intention of going to St. Marks, and had made many gay little plans for entering the very avant-garde New Trends High School. Mama had no intention of sending me to New Trends and had planned to enter me in the freshman class of St. Marks. Age and money were on her side, always, and, as I had my uniform fitted one hot August afternoon, I had the feeling that St. Marks and I would not see eye to eye, any more than Mama and I did.

I had loved the New Trends Grammar School. It was my favorite place. It was at New Trends that I had learned to grow sweet potato plants, play the silent keyboard, and sing. The rest of my preliminary education was fairly sparse. It wasn’t until my father realized that I couldn’t add or spell that he thought I should be sent to the nuns.

My father had been paying one dollar a week for me to learn the piano. At New Trends, we worked on a long cardboard keyboard that opened out three times. Even if you had a piano at home, you weren’t supposed to play on it.

“Why don’t you use the piano?” Papa asked crankily one night.

“I can’t play on that,” I said, aghast that he would suggest such a thing.

“Well, who in the hell is going to want to hear you at the silent keyboard?”

“It’s not time yet.”

“Time for what?” sneered Papa.

“It’s not time for us to come out of our musical cocoons. I’m crystallized,” I told him.

“You’re nuts, that’s what.”

And that’s when it all began. Mama convinced him that I should finish New Trends and graduate and then the nuns would take over.

In preparation for graduation, Miss Home, my eighth grade teacher, had asked us to please print our correct names on the cards she would distribute. No nicknames like Sally or Bunny or Peggi. We were to put down our real names. She passed out the cards and we all fell to writing our full and proper names on them.

“These are for your diplomas,” she added:

I hated my name. Jane. What a dumb name. Plain Jane. Pain Jane. Arcane Jane. None of them suited me. I was the more glamorous type.

What I needed was an exciting name and I would give myself one. I was reading a book where the heroine’s name was Adrienne. I printed that as my first name. Now what would go well with Adrienne? I peered over my shoulder at the little girl in back of me. Her name was Mary Frances Carroll. Frances. . . . I thought. No, that’s not exotic enough. Francine. Francine. That was beautiful. I printed in: Francine.

When Miss Home picked up the cards she looked at mine.

“I thought your name was Jane.”

“Just for short,” I said.

Miss Home was supposed to check them against the records but she obviously didn’t follow through.

The night of graduation, I shook through the whole ceremony. When they called “Adrienne Francine Trahey” there was a slight murmur from where my family sat.

My father poked my mother and said, “I had no idea there was another Trahey in her class.”

“There isn’t,” Mother said, knowingly.

My father sighed. “What if the nuns don’t take her?”

“They will,” Mother said with determination. As usual, she was right.

The Convent of St. Marks was not only a school, it was also the Motherhouse of the Order. It was here that the young Sisters attended novitiate and the old Sisters came home to die. The school ran almost incidentally. The old building was nearly a hundred years old, the new school was only fifty. The whole Megillah sat on the side of a hill overlooking a soft flowing river—much like a huge, fat old lady sunk in a cozy chair.

The architecture was pure King Arthur—turrets, spires, niches, stone. It was a formidable home away from home. Fortified by a nine-foot stone wall and a gate that had everything but broken beer bottles on top, it lacked only a moat and drawbridge to completely isolate us from the outside world. If the truth be known, Mother Superior had undoubtedly tried to cajole the Fathers’ Club into digging one.

Roger, the janitor, and Miss Connelly, who we surmised by her build was the gymnasium teacher, met the few of us arriving on the 5:15. I had noticed a wizened-faced blond girl smoking a cigarette on the train and hoped upon hope that she would be going to St. Marks.

Some little old lady who sat next to her told her she was shocked to see a child that age smoking and the blonde merely looked at her through the cloud of Twenty Grand smoke and said, “Madam, I am not a child, I’m a midget.”

When the conductor called the station, she stood up, and St. Marks already seemed a livelier place.

“Line up girls, line up. Everyone for St. Marks, line up,” Miss Connelly shouted.

She seemed to me to be overdoing it a bit, as there were just four of us and the most we could do was huddle together.

“I’m Miss Connelly,” she said, “and I’m part of the lay faculty at St. Marks. Now, if you’ll all line up we’ll count heads.”

This seemed ridiculous to me since it wasn’t any strain to figure there were four of us.

“When I call your names, please answer ‘here.’”

The blond girl whispered to me, “Let’s not answer.”

“Okay with me,” I said.

She got her message to the other two and we all lined up.

“Clancey.”

There was no answer.

“Trahey.”

I kept mum.

“Schlessman.”

She seemed restless, but went along with the gag.

“Wertheim.”

Miss Connelly turned the card over to see if by any chance she had been reading the wrong side.

Schlessman began to titter and the blonde gave her a withering look.

I adored this girl. She was the most composed criminal I had ever met.

“Aren’t these your names?” she asked incredulously.

“No, ma’am,” the blonde said meekly.

“Well, who are you?” she said, digging into her military knapsack for a pencil. She put the card up against the station door and said, “All right, now spell out your names, one at a time.”

Obviously, she dealt with low I.Q. children, as everything she did had an institutional quality to it.

The blonde began, “F-a-y—” She paused.

“First or last name?”

“First,” the blonde said.

“Last.”

“W-r-a-y.”

Spelling it out this way made it seem more possible,

I suppose, to Miss Connelly, since she never batted an eye.

“Next,” she said. It was my turn. Apologetically she said, “Mother Superior must have given me the wrong list to meet.” Secretly, she seemed delighted to

have all these problems. It was sort of a oneupmanship on Mother Superior.

By the time she loaded us on the bus she had carefully copied down our names. We were delighted with ourselves and, for a moment, forgot to be homesick. Before Miss Connelly could blow her whistle, we all had new names and I obviously had a new friend.

Miss Connelly smiled and chatted with us all the way, reassuring us that we would be very welcome, despite the bad beginning on St. Marks’ part. She was a serious, hard-working girl, the kind of faithful St. Bernard who finds they can’t leave the school, so they teach in it. With care and diligence she ran us into the main hall of the building. Everything Miss Connelly did was paced toward the Olympics; she did not walk, she slowly trotted. By the time we got to the office, we were all a bit out of breath. It was a hot September afternoon, stifling as only Midwestern Septembers can be. Like the movie-house slogan, it seemed to be twenty degrees cooler inside the convent, though this slogan, we learned, held just as true in the winter as it did in the summer.

“Now line up nicely,” she urged, “and I’ll find out how I met the right train with the wrong list.”

When she left, the other two girls seemed worried. “I don’t think we should go on lying.”

“Your name,” said the blonde sternly, “is Lemmon,” and she turned to the tallest girl and said, “And your name is Bottom.”

They didn’t want to play. I said, “My name is Pawnee and I’m a full-blooded Seminole.”

“That’s right,” she said, pleased with me.

I was delighted with her.

“Girls, this is Mother Superior,” Miss Connelly said. We heard her first, a soft rustle of beads, a swish-swish—it was a sound that would haunt me for my days at St. Marks.

And there she was, the High Lama of the Lamasery. She seemed to be about eight feet tall with swarthy skin, black eyes, and bushy eyebrows that thatched above her glasses. She looked medieval. She held her hands under her front cape on her habit and observed us quietly. I suppose we were a typical sampling of every freshman class she could remember.

One of the girls, the tall one, giggled, and Mother’s look was like a quick slap.

Her voice was of cut glass. “How do you do.”

We all coughed back in answer.

“Mother,” said Miss Connelly charmingly, “there seems to be some mistake. I was supposed to have picked up these four”—she handed Mother the card—“and instead, I got these four.” She headed toward Mother Superior and leaned over, pointed to her own printing and read out, “Wray, Lemmon, Bottom and Pawnee.”

“Did you know she’s a pure Seminole?” she said aside to Mother.

“Really,” Mother Superior said, “really, I had no idea we had any pure breeds in this class at all. Which one of you is Pawnee?” she said, smiling coldly.

At that moment, I rather wished I had said I was Bottom or Lemmon.

“I am,” I stuttered. I tried to look and sound as Indian as I could, which wasn’t easy with my pale coloring.

“And what is your first name, Pawnee?” Mother Superior quizzed, much as an Indian chief might ask at a burning ceremony.

“Black Sock.” I could hardly say it, I thought it was so funny.

Miss Connelly looked impressed.

“And you, Miss Wray, what is your first name?”

“Fay,” the blonde answered coyly.

“Fay Wray,” Mother said. “My, that’s pretty. And Miss Bottom?”

The girl completely forgot her first name was Sandy and Mother Superior said to Miss Connelly, “You take Miss Bottom and I think you can take Miss Lemmon to Sister Portress. And you can go on and meet the next train. I know you’re anxious.” She looked at the two of us. “I think that I would like to get to know our Indian friend and Miss Wray just a bit better.”

Miss Connelly flexed her sweatered muscles and shepherded the two other girls out of the room. Fay and Mother Superior and Black Sock headed for the other side of the building, where Mother Superior made it clear that she did not appreciate this kind of tournament.

“I suppose you”—she flipped through her cards and pulled out one that she read—”are Mary Clancey.”

The blonde smiled and said, “That’s me.”

“A simple ‘Yes, Mother’ or ‘No, Mother’ will do.

“And you”—she looked at me—”you must be Adrienne Trahey.”

“No, Mother,” I said miserably, “I’m Jane.” Stumbling badly, I tried a light explanation of my various monickers.

“And so your

real

name is Jane,” Mother Superior said resignedly.

“Yes, Mother.”

“I do not know what you were taught at New Trends,” she added sternly, “but I want you to forget it. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Mother.”

“All right, you can both go now. I hope that we will not meet again under this type of circumstance.”

We scooted out of her office and went wandering through the empty corridors. Jane Trahey and Mary Clancey. I felt as if I had known her for years.

“Let’s go have a smoke,” Mary said. “I’m dying, simply dying for a smoke.”

Suddenly St. Marks looked brighter to me than New Trends ever had.

Chapter Two: The Secrets of the Cloister

Even though there were a hundred-odd clocks at the

convent, everyone told the time by Sister Melchior’s

bell. Now this was no ordinary bell that rang auto

matically. It could neither be pushed into action with

Sister’s long mystical finger, nor slapped into action by electric clocking. This was a plain, old-fashioned silver

hand bell, about the size of a pear, and Sister Melchior

swung it with the same authority the early fathers of

our country must have had ringing the Liberty.

Just before six in the morning, Sister Melchior made

the rounds of all the sleeping quarters, in and out of

the cloister, ringing her bell till you could wring her

neck. From that moment of awakening, right on

through the day—lunch, dinner, study, recreation and

finally praying one’s way to sleep—you could listen

to her softly retreating clang as she padded along the halls on her healthy, black leather arches.

Sister Melchior was in fact a veritable symphony of sounds with her squeaky shoes, her clicking beads and

her pear-shaped bell. Naturally, we called her Paul Revere and told all the newcomers to the school she

was a German princess who had lost her mind because

they (the German king and henchman) had thrown

her lover in a moat filled with crocodiles. Nevertheless,

all the time we owned in the world was at the helpless

mercy of her swing.

She had been portress of the convent as long as I

could remember. Her station was just inside the great

front door. Front doors are never used on convents.

Side doors are always used. Only parents and visitors

use front doors. Sister Melchior’s desk was at the top

of five highly polished and superwaxed steps. She kept

a tiny, green-shaded light on at all times as it was dark

in this part of the convent. From her perch she could view the front door, both side doors, and almost all

the comings and goings of the entire convent. She

guarded us like a great medieval dragon, sitting directly between the cloister front door and our world.

We had been told in no uncertain terms, from the moment of arrival, that the cloister was out of limits

to all of us. Woe be to the student who was found in it.

“Young ladies, a portion of this building is the holy

cloister.” Mother Superior peered out over her oc

tagonal glasses and her black eyes pierced mine. “Do

we all understand this?” I nudged Mary Clancey, who

was cleaning her nails with a holy card corner.

“It is strictly forbidden for anyone of you to enter

any

door in this building that is marked ‘Cloister.’ I presume you all read.”

“Sarcasm, sarcasm, the devil’s weapon!” whispered Mary.

“Miss Clancey seems to feel that her message to Miss Trahey is vastly more interesting than any message I might want to give to her.” Mother Superior glared at us.

“I’m terribly sorry, Mother,” Mary apologized, “but I thought Miss Trahey was going to faint, and I merely asked her if she felt all right.”

This threw me into a complete panic and it was exactly the sort of thing you could expect from Mary under pressure. But that was one of her weaknesses—and she had so many charms.

“Well, just hang on another minute, Miss Trahey, and you can,” she snapped back.

“This is the Sisters’ home. You wouldn’t want strangers roaming about your house. We do not want them in ours. If”—and she let us hang on this word for almost a whole minute—”if I ever find one of you in the cloister, you will have only me to reckon with.”

The thought of this was both frightening and challenging. For Mother Superior had not taken an instant dislike to Mary Clancey and me; it was rather like a stone that gathered moss. We had only been around her a few days and already this dislike was being cultivated by all three of us.

The moment I met Mary, I knew that life at St. Marks could be palatable and exciting. Perhaps not as inspiring as I daydreamed about life, but at least bearable. From the beginning, the Sisters did everything in their power to separate us, but with so few students it was impossible to teach everything twice just to accommodate us. We seldom got a chance to be

together, but upon occasion we managed to elude both students and faculty, and devoted ourselves completely to the downfall and destruction of Mother Superior.

“The best time to go through the cloister is prayer time,” Mary said to me as soon as Mother Superior left the room. “They’re good for at least an hour.”

“We’ve got to have someone watch the door and let us know if someone comes.”

“How do you feel about Murphy?”

“Okay with me.”

Murphy was our first choice for a friend if we had to have a friend. She was what my father called a “slick” mick. This was opposed to the other breed of Irishman known as “thick” micks. In all the time that Mary and Murphy and I sewed the Sisters’ nightgowns at the neck, locked their bathroom doors from inside and climbed out windows, Murphy invariably made the honor roll. Mary and I were not only never on the honor roll, we were on Mother Superior’s blackest list.

Murphy’s mad, cinnamon-colored eyes sparkled at the thought of a tour of the cloister.

“Sure, I’ll watch the door.”

“You had better whistle if anyone comes.”

“I won’t be there if anyone comes.”

“Aw, come on, Kate, be a sport or we’ll never see how the other half lives.” Mary wiped her sweating palms in pure anticipation of the tour.

It was so easy to see the cloister, we were really quite disappointed. We rambled from room to room. Most of them were bedrooms or large dormitories where the novices slept. The whole place looked like a charity ward in some hospital.

We made a special point of finding Mother Superior’s room. It was as bare as the rest of them. I suppose we expected to find the trappings of an early Medici, but it was not like that at all. A crucifix on the wall, a chest of drawers, books piled on the chest and not a one of them interesting.

Then we took in the refectory, the recreation room and the baths.

“Well, how was it?” Murphy quizzed us. “See any hair shirts or racks or chains?”

“Hell, no,” Mary said, “it’s as dull as the rest of this place.”

“Listen,” Murphy confided in us. “I’ve been thinking. I bet we could sell tours through the convent. Everyone wants to see it and no one has the guts to look. If we’d take them for a quarter, I think we could have a lot of fun.”

Mary was delighted. The thought of dealing so crushing a blow to Mother Superior was a real thrill. “First of all,” she said generously to Murphy, “you have got to see it.”

So Murphy took the tour and from that moment the “Cloister Tour” group went into business. “Want to see where the Sisters and Mother sleep?” It was foolproof. No one would open their mouths because they either wanted to go or had been.

Occasionally some good girl would say, “It’s forbidden.”

“Of course, it’s forbidden if you get caught, but who’s going to get caught?”

As the year progressed, we took the younger groups and even some of the graduating seniors. The more we took, the more business we had. Children who had never done a wrong thing in their school life went simply because they were compelled to go. No one could resist seeing a cloister.

We even thought of hiding some knotted ropes around and saying we had found a secret torture chamber, in order to get some repeat business. By the end of six weeks, we had toured just about everyone at twenty-five cents a head. We couldn’t have been more pleased had Mother Superior contracted a fatal illness.

One afternoon, two of the biggest sticks in the whole school came to see us. We had never expected them to fall.

“How much do you charge for the tour?” asked Florence Mackey. She was a pet hate of Mary’s and mine as she was the only one we knew who bathed regularly. She and Lillian Quigley were our leading lights, constellations in Mother Superior’s crown. They could do no wrong.

“Thirty-five cents.”

“Your price has gone up,” they said smugly.

“It’s getting more difficult all the time to just handle the traffic.”

“I don’t think it’s worth it.”

“So skip it.”

Finally, we agreed to take them at the usual fee and they accepted. We told them to meet us at the cloister side door. The time was twenty-five minutes to five. The Sisters all went to prayers at four-thirty, and five minutes after it began, they were hard at it.

Florence and Lillian were both there and quite nervous.

“You’re sure we won’t meet anyone?”

“They’re all at prayers.”

“What about Sister Portress?”

“She sits at the front door. We never go near it.”

“Well, there might be something to see there.”

“Look, if you two want to go on by yourselves, feel free.”

Mary was obviously peeved, but getting these two to go at all was such a feather in our caps we couldn’t let them out.

We were wasting too much time. We waited until the few stragglers of the faculty appeared at prayers late (they were always the same ones) and then we started. We knew there were two sick Sisters and we would have to avoid the hallways in front of their rooms. We kept the tour on the main road: Mother Superior’s room, bathrooms, recreation rooms, dining rooms. For some strange reason, the dining room fascinated the tourist more than anything else. The long polished tables were gaunt and bleak-looking and at the far end of the room stood a podium with a bookstand. A great black book was open, perched on it. At the other end of the room was a sink where the Sisters washed their own plates and knives and forks. It did not resemble the Jolly Tea Room.

The convent at this time of the day had a shadowy quality, as it was just beginning to get dark. Our spooky shapes reflected along the walls and polished floors and sent Florence and Lillian into a cold sweat.

Mary was the leader, then the tourists and, up till that very day, Murphy brought up the rear. We felt, however, that the profits of this particular venture could be all ours, so we did not include Kathryn in our tour. This, then, was my first day in the rear echelon. At least, I thought I was the last one in line. I never knew how long Mother Superior had been following os. What she did was inexplicable.

She merely locked every door after me and there has never been such a trap set before or after that day. We confidently strolled through the convent explaining the various spots. We showed them “her” room, their homeroom teacher’s room, and even gave them the added thrill watching a sick Sister thrump-thrump-thrump down the hall on her way to the bathroom. She was wearing a long white gown, a tiny cap and a flannel bathrobe. Lillian and Florence were in total shreds.

“We’d better blow,” Mary said, “they’re beginning to break.”

I pushed the exit door that led back into the non-cloistered part of the building. “Okay, this is the end of the tour; on your right you will find you are on the right side of the gymnasium,” I chanted to them, like the tour man I had seen at a carnival.

Mary said, “The door’s stuck, give me a hand.”

“Don’t be an idiot,” I said confidently. “Here, let me try.”

I shoved, and Mary shoved, and Florence shoved, and Lillian shoved.

“You promised we wouldn’t get caught.”

They both began to cry about their gold ribbons and the shame of it all. We tried all the usual exits we had ever used. They were all locked. We were indeed caught in the trap. We were in the cloister. It was then Mary and I decided to run for it.

“Come on, let’s shake these two and Mother Superior will merely think it’s them,” I whispered. I was the sort of spy who would have turned in his grandmother.

Mary nodded and we twisted in and out of corridors and around the halls. We knew them like a book. It was beginning to get dark out and the halls were deathly still. Finally, Mary spotted an exit, and said “Thank God.”

It was the fire escape—an old-fashioned sort of Coney Island ride that was fitted on the outside of the building and made of metal. It was the sort of chute that had an exit on every floor so that anyone could hop in it and be safely delivered to the ground. It was on the back of the building, and we had been to fire drills twice that year and used it. It was pitch black inside and Mary gave me a shove. I flew down the escape hatch, jubilant over the fact that Mother would find the two honor students, Florence and Lillian.

I felt as if I had hit bottom and could kick the door to the outside with my foot. I waited for Mary to join me and I heard her whirring down.

“Well, here you are,” I said, grabbing her shoulder in the dark. We practically embraced with the good feeling of having just, for a change, not been caught.

“Come on, let’s get out of here,” Mary said. I kicked open the door. The air smelled crisp and fresh and cold. One came out of the chute in a sitting-down position. I struggled out, being first, put my feet on the ground, and stood up and held the door open for Mary. It was almost dark in the late winter twilight, but it was light enough for us to recognize instantly the familiar shape of Mother Superior waiting for us. In fact, she helped steady Mary.

“Well, now,” she said, “where’s the fire?”