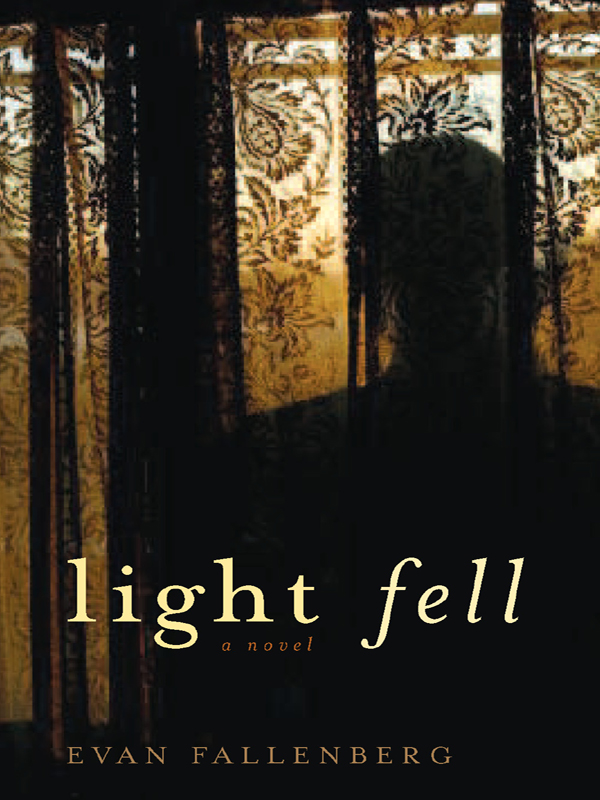

Light Fell

Authors: Evan Fallenberg

light

fell

light

fell

EVA N FALLENBERG

Copyright © 2007 by Evan Fallenberg

All rights reserved.

Published by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, New York 10003

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fallenberg, Evan.

Light fell / Evan Fallenberg.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-56947-467-9

ISBN-10: 1-56947-467-2

1. Family-Fiction. 2. Tel Aviv (Israel)—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3606.A43L54 2007

813'.6—dc22

2006051248

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Micha and Hagai

Contents

Writing a novel is a long and lonely business. I have been helped along the way by many wonderful people and institutions:

Rabbi Steven Greenberg and Lieutenant-Colonel (Res.) Hezki Malachi enabled me to enter the heads of several characters initally inaccessible to me.

Professor Norman Roth’s fascinating article, “Deal gently with the young man: Love of Boys in Medieval Hebrew Poetry of Spain” (

Speculum

57, 1), introduced me to several astonishing poems penned by famed rabbis.

Abby Frucht, Mary Grimm, Ellen Lesser, A.J. Verdelle, Phyllis Barber, Miriam Beilin Wrobel, Joan Leegant, and Eve Horowitz read the manuscript at various stages and made comments that caused me to reassess and revise. Joan and Eve were also tremendously generous in sharing their experiences and accrued wisdom.

Deborah Harris and Ines Austern provided excellent advice and comic relief, each at the right time.

Dena, Rosalie, Marc, and Esther Fallenberg did what families do: criticized, comforted, cheered.

Vermont College, The MacDowell Colony and Soho Press opened the way to opportunity.

Publisher Laura Hruska welcomed me to Soho Press and editor Katie Herman polished my manuscript with professionalism and grace.

Finally, the love, strength and encouragement I received from Yonina Weinreb Fallenberg and Yariv Levin set me on a new path of freedom and creativity.

—Evan Fallenberg

FRIDAY, MARCH 1, 1996

T

HE BOYS SEEM NOT

to notice the stench of rotting fish or the shards of bottles, driftwood, and jagged shells jutting up out of the sand. In search of something along the water’s edge, they remain oblivious to the icy wind that stings and bites them. Joseph, without his first-aid kit, winces at the thought of needle-sharp fish bones piercing the soft soles of their feet. But he is preoccupied with the twins, still babies, and lets the older three slip from his sight to disappear past the rotting pier. They would not hear his shouts over the ceaseless roar of the sea, so he does not bother. But should he scoop up a twin under each arm and run toward the pier? And why is he alone with all five boys on a cold winter beach? Panic foams upward inside him like bubbles on an angry sea.

He catches sight of them running away in a line—Daniel, the eldest at seven, in the lead, with Ethan and Noam close behind, their pace synchronized like miniature soldiers on a mission. Suddenly a solid wall of gray water rises as if from the heart of the sea. The boys stop their playing and turn to call for Joseph’s help. But they are too far away and he can-not hear their screams. He can only see the terror that magnifies and distorts their tiny faces. He lets go of the twins as he stands to watch the wave claim his three older sons. Before looking down he already knows the babies have vanished, too, his own body submerged to the neck.

Joseph Licht awakens, drenched. It takes him a long moment to realize he is sweating under the heavy comforter and longer still to understand that his head is wet from the rain blowing slantwise in sheets through the open window. He pushes aside the comforter and sits up quickly, indignant. The carpet is soggy and the papers on his nightstand translucent. Joseph bounds out of the bed and skids in a puddle, slamming the window shut. He turns to face the priceless Géricault nude he moved from the living room only last night and sees that the rain has darkened the wall beneath it and spattered the gilt frame but has not reached the canvas itself. Hands on pajamaed hips, he stares hard at the painting through lowered lashes. An art treasure, in his bedroom, nearly destroyed. He imagines restorers in white lab coats working to return it to its original glory and Pepe, shocked at last, throwing him out into the street. Sitting on the edge of the bed, he gathers the reassuring comforter around him and takes stock: the painting is unscathed, the papers will dry just fine in the sauna, and if Joseph can let himself believe it, on this very Sabbath, right here in his beachfront apartment high above Tel Aviv, he will be celebrating his fiftieth birthday with his five sons—all old enough to be fathers themselves— marking the first time in nearly two decades that they will all be together with their father.

Joseph’s image in the bathroom mirror this morning does not entirely displease him. Though no longer a man who turns heads, he knows he looks good for someone his age. On a good day he can pass for ten years younger— thirty-eight even. Joseph has found the right shade for his hair, a metallic color suggesting gold and silver and reminiscent of the blond he once was. This keeps him from looking like an old fop, the kind whose very forehead takes on a hennaed sheen. The wrinkles in his face are still fine lines. He is no longer thin, but neither has he gone soft and doughy.

In the kitchen Joseph perches on a stool at the counter, upon which he has arranged computer printouts of his to-do list and the weekend menu. He pours hot brewed tea into an antique porcelain teacup, tracing the floral border with his finger. The rising steam paints a cloud on the window and Joseph looks beyond it to the dull gray sea, the empty beach bereft of little boys on crucial missions. Down the coast even Old Jaffa is mellow and subdued on this midweek winter morning, crazy strung colored lights breaking up and refracting back at Joseph through drops on the windowpane. With a red marker he crosses off completed items from his list: cookies, potato kugel, ratatouille.

He has given long and careful consideration to planning the menu for this reunion, each item chosen for the effect it will have on his guests’ emotions as much as on their palates. Twenty years ago he left his wife, Rebecca; their five sons; his father, Manfred; the moshav where he grew up; all his friends and acquaintances—in short, his life of thirty years—when he fell in love with the Rabbi Yoel Rosenzweig, a dynamic young teacher-scholar hailed by all as an

illui

, a Torah genius, perhaps the greatest of his generation. In his old life Joseph had never held a dinner party, never hosted other than on the sporadic Sabbath. Back then the objective of hosting was to create an environment entirely recognizable to all the participants: no vegetables other than squash and carrots for the standard chicken soup, no exceptional sauces for the required chicken, no exotic seasonings for the potatoes. The only surprise in the Friday night meal came at its conclusion, after the singing of the traditional Shabbat melodies, when the sated guests had been mollified. Only then might they be expected to face with equanimity a chocolate cake or poppy roll or apple pie.

Joseph’s rebellion was thorough: he has neither eaten nor served those foods on a Friday night since. Now the most humble of his meals is a lemon and artichoke chicken that he is careful to serve with Thai rice or Chinese noodles, or fresh corn on the cob in summer. A meal hosted by Joseph may begin with a sorbet or fruit salad, the main dish accompanied by honey-glazed sweet potatoes or fresh greens with a drizzle of orange and mint. His desserts are the talk of his circle, designed to leave his panting guests cursing themselves for poor pacing.

Joseph lifts his teacup in a toast to his own cleverness. He has, after all, succeeded in planning a perfectly traditional set of Sabbath meals while maintaining his own hard-earned panache. And most important, every dish will be on the table for a precise and celebratory reason, either because it was a food one of the boys once loved or because it will jiggle loose a crystallized memory or because it will provide a topic of conversation if none is forthcoming. There will be chicken soup and chicken, but the soup will be a highly refined version of Rebecca’s—the noodles, rice vermicelli, and the chicken, stuffed breasts. Potatoes, too, but in the form of

roesti

, which Joseph learned to prepare from Rebecca’s mother and ultimately personalized by adding onions fried lightly in beer. Knowing that his middle son, Noam, loves red meat, he will grill cubes of the choicest beef seasoned with basil and coriander. Through effective detective work he has learned that Gavriel is still a chocolate fanatic, so in his honor Joseph has included a dark chocolate mousse with amaretto. And for Gavriel’s twin brother, Gideon, who has abandoned the family tradition of modern Orthodoxy for ultra-Orthodoxy—and as far as Joseph is concerned, aesthetics and good taste for stringent religious observance—he is inaugurating newly purchased sets of cookery, cutlery, and crockery, dutifully immersed in a ritual bath precisely according to Jewish law.

There will be a lot of other dishes, too: a light Corsican ratatouille, fennel salad, tossed greens with heaps of olives and croutons (the boys used to pick these out and fight over them), three vegetable casseroles in the unlikely event that Gideon’s wife—Joseph’s sole daughter-in-law—doesn’t eat meat, and a wonderful Brazilian fish recipe that includes mustard, wine, peanuts, and coconut. The last is a dare: he will mention Pepe and Brazil only if things are going exceedingly well. Last night he baked oatmeal cookies for munching and one of today’s projects is a huge iced angel food cake, the kind the boys always requested for their birthdays. This time the Birthday Cake, as they called it, is for Joseph himself.

He slides off the stool, removes the glazed-glass bowl of blueberries from the refrigerator, and rinses them carefully at the sink. After all his cautious planning, these unanticipated fruits are the most special food of all, a good omen for the coming reunion. They are at once a beloved treat, a memory, and a topic of conversation. Afluke. Asign. Just as Joseph was roaming the

shuk

, filling his basket with edible memories, he saw them, “. . . big as the end of your thumb / Real sky-blue, and heavy, and ready to drum / In the cavernous pail of the first one to come!” It was that poem that had spurred him, at the height of his infatuation with Robert Frost, to take the family berry picking in western Massachusetts in the frenzied days before Rebecca and the boys returned to Israel, leaving Joseph alone in Cambridge to finish his doctoral dissertation. The oldest boys, Daniel and Ethan, had wanted to see “. . . fruit mixed with water in layers of leaves, / Like two kinds of jewels, a vision for thieves,” and Rebecca had readily agreed, eager to blot out the tantrums and rages to which Joseph had been subjecting them all and hoping the boys could take back with them to Israel new and better memories of their father: Joseph at peace in nature rather than seething with frustration in front of the old Hermes typewriter they had filched from Rebecca’s mother, or raising his hand as if to strike them.

The berries ripened outrageously early that year. Even Joseph had known that the fruit should not have matured until August, so he wasted no time in arranging the outing when his adviser reported, after an early July weekend visit to his summer house, that the surrounding countryside was bursting and ready for picking.

A photograph from that day stands out among all the others on a glass-topped table in Joseph’s living room. It was snapped by a local farmer’s son awed by the sight of the young couple with their five boys, slight variations of one another, all blond, all healthy, all full of confidence, energy, and curiosity. Rebecca had laughed when the young man said she and Joseph looked like brother and sister, but this had annoyed Joseph; he had always been uncomfortable admitting they were second cousins, a fact of which their resemblance was an unwelcome reminder. Now, after more than twenty years, he can see how he and his wife were similar and how they were not; much like a peacock and his peahen, their features were nearly identical, but on him sharper, clearer, more highly colored. His hair lighter, his eyes brighter, his smile broader, his teeth whiter. She was a faded version, a smudged copy. Still, the photo features youthful parents, not yet thirty, smothered by the chubby twins, at twenty months already trying to keep pace with the older ones, hugging, squeezing, and toppling one another. Daniel at seven, Ethan just turned five, Noam not quite four. All seven Lichts in full laughing motion, limbs flailing, eyes crinkled in absolute gaiety. No movie camera could have portrayed the excitement or hidden the anxieties with more fidelity than did the still camera of that Massachusetts farm boy on that summer day in 1975.

Just yesterday Joseph watched his Nigerian house cleaner, Emanuel, pick up that photograph from the glass-topped table, watched him dust and study it. Emanuel dusted others, too: the boys collecting eggs from the henhouse as toddlers; slightly older, riding bicycles, tractors, horses; and later still, somber faced in army fatigues, as if ready for anything in the name of God and country. He dusted the single black-and-white photograph of Pepe’s daughter, Carolina. But Emanuel did not pick up and look into those other photographs as he dusted them, only the one of the berry pickers, the model family with its promise of perfect happiness.