Lilla's Feast

Authors: Frances Osborne

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 - THE SWEET SMELL OF SPICE

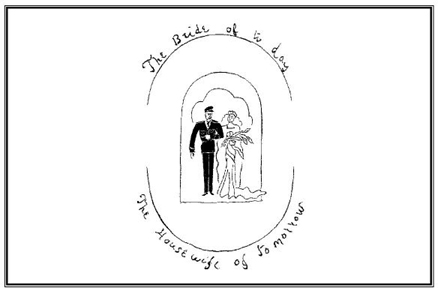

Chapter 3 - A “NOT QUITE PRUDENT” MARRIAGE

Chapter 5 - “POOR LITTLE LILY”

Chapter 6 - MELTING BITTER LEMONS

Chapter 7 - IN THE LAP OF THE GODS

Chapter 12 - RICE-PAPER RECIPES

Chapter 13 - EATING BITTERNESS

Chapter 19 - HEAVENLY TWINS TOGETHER AGAIN

Reading Group Questions and Topics for Discussion

For Luke and Liberty,

two of Lilla’s many

great-great-grand children

CHOSEN AS A KIRIYAMA PRIZE NOTABLE BOOK

PRAISE FOR Lilla’s Feast

“

Lilla’s Feast

. . . tells the remarkable tale of an ordinary woman and her extraordinary life.”

—

Minneapolis Star-Tribune

“A new and absorbing book . . .

Lilla’s Feast

is a stunning example of a woman who triumphed over adversity.”

—

El Paso Times

“A must-read.”

—

The Daily Oklahoman

“A feast for the reader . . . For those of you who like adventure, history and love stories with food thrown in, don’t miss

Lilla’s Feast

. . . . It’s fascinating reading.”

—Fort Lauderdale

Sun-Sentinel

“I loved

Lilla’s Feast

—absolutely absorbing, both for its historical content and its personal details. I felt for Lilla, every step of the way. A real feeling for place fills this book. . . . Lovely.”

—MARGARET FORSTER,

author of

Lady’s Maid

“A captivating narrative of one resilient woman’s one-hundred-year journey through the cultural changes and political turmoil of the late nineteenth century and most of the twentieth.”

—JOANNE LAMB HAYES,

author of

Grandma’s Wartime Kitchen

Author’s Note

In 1976, English-language newspapers changed from the old Wade-Giles system of romanizing Chinese names to the modern Pinyin. As Lilla’s story is set in the past, nearly all of it prior to 1976, I have used the Wade-Giles system. The Chinese names in this book are all therefore written differently today. This may give the impression that the places Lilla inhabited no longer exist. And, as you will discover, they don’t—at least not as she knew them.

PROLOGUE

In the Imperial War Museum in London, there is a cookery book. It’s there because it was written in a Japanese internment camp in China during the Second World War. When the book was given to the museum back in the 1970s, prime-time television was still packed with dramas about Japanese prison camps and the war, and the museum put it on display in the front hall. Thirty years later, it has slipped farther back in the building, into one of the galleries about battles we’re growing too young to remember.

There, its old-fashioned Courier-type pages lie open, each chapter a rusting, paper-clipped bundle of different-colored leaves. Most sheets are scraps of what was once white paper but has now yellowed with age. Some are torn from old account books. Some have AMERICAN RED CROSS stamped on the back in red. There is even the odd blue sheet of Basildon Bond writing paper. And many of the pages are typed on blank rice-paper receipts so thin that you can see right through them and marvel at how they survived the click and return of an old metal-bashing typewriter, let alone the war during which the recipes were written.

It’s when you actually read the book that the real surprise comes. For it’s not what you would expect from a wartime recipe book—all rations and digging for victory, or subsistence on rotting vegetables and donkey meat in a Japanese internment camp. It’s quite the opposite. It’s a book that’s written as if the war wasn’t there at all. As if everyone was back in their warm, safe homes with their families and friends, the larder full and the table heaving with fresh, just-cooked food. It gives advice on how to make good things last longer, how to live and eat to the fullest. The pages are jam-packed with recipes with old-fashioned names: cream puffs and popovers, butterscotch and blancmange, galantine of beef and anchovy toast, jugged hare and mulligatawny soup. There are dinner-party menus, children’s menus, cocktails, ice creams, sweets. It’s a book for making the best of times in the worst of times, a book that makes you believe that if you could fill your mind with a cream cake or anything delicious, then you could transform the bitterest experience into something sweet and shut out the things that you need to forget.

And that’s what my great-grandmother, who wrote the book, believed.

My great-grandmother’s name was Lilla. She’d been christened Lilian, but her stutter stopped her from reaching the third syllable. So Lilla it was. I remember her vividly. She didn’t just survive the camp, she lived for another forty years—until she was almost one hundred one and I was almost fourteen. Even at the end of her life, she was extraordinarily elegant, her long hair gently twisted up at the back of her head, her enviable legs always neatly crossed, and only ever wearing fitted black lace and white diamonds that sparkled like those still burning, bright blue eyes. When we children scuttled through the door, this slim, birdlike creature would lean forward from where she perched on the edge of a sofa and whisper that it was “w-w-wonderful” to see us, as she could never understand what the grown-ups had to say. In ten seconds flat, we had fallen under her spell. Jumping over the two bossy generations in between, our great-granny was our ally.

Lilla made the end of her life appear effortless. She trotted a mile to the shops and back each day. She had more descendants than she could count. Her bedroom was a through-the-looking-glass museum of furniture, pictures—even costumes—from each country of the world in which she had lived: China, where she had been born; India, where she had been a wife; England, where she’d ended up when she had nowhere left to go. She behaved as if she had sailed through life and nothing could have been better.

She rarely mentioned the camp.

Still, there were a few snippets that didn’t add up. A few phrases that slipped out in those gray hours after the funerals of each of her two children. There were her three “husbands” waiting in heaven and her worry as to which one she should live with “up there.” If any of them. There was an allusion to a “real father,” who had shot himself, she said, when she was very young. There was her obsession with having something to leave her children and grandchildren. And there was the unheard-of child whom, in a whispered confession, she said she had made herself miscarry.

At the time, these were mysteries that simply added to Lilla’s exotic charm. It was only years later, when I started to unravel them, that I began to realize that they were, in Lilla’s way, cries for help. Calls to understand that, beneath its polished surface, Lilla’s life had been far from effortless. Clues not just to the pain of internment, which at least she had shared with others, but to another story, one that she had endured alone.

A trail of dozens of surviving friends and relations—there’s a tendency to longevity in our family—led me to the British Library. There, I soon found myself staring at a long, thin box thickly packed with faded letters that had flown between Lilla, her first husband (my great-grandfather), his parents, and his siblings, almost exactly one hundred years ago. As I pieced together the story that unfolded in them, I began to cry. Salty tears ran down my cheeks and dropped onto the thin paper letters, almost washing the words away. I wiped my face with a handful of tissues, smearing mascara around my eyes until I looked like I’d been in a fight. One of the librarians came over and asked if I was all right.

Emotional outbursts must be rare in those dimly lit reading rooms on the Euston Road. It took me two years to return. When I walked back into the Oriental and India Office Reading Room, changed, a mother now, and hoping to be able to judge the story in a more objective light, the librarians recognized me instantly. And almost before I could ask, they had gone to retrieve that old ballot box whose contents had made me cry.

The letters I read made me understand how Lilla had found the will to write those recipes. If it hadn’t been for what she had been through long before the camp, I’m not sure she would have had the determination, the imagination, to shut out the bad things by writing down not just the odd recipe, but a complete cookery encyclopedia that runs chapter by chapter, from a “course of cooking” to soups to fish to game and on to hints on homemaking. And get right to the end.

My father was always the one who was going to write Lilla’s—his grandmother’s—story. I remember him standing on the first-floor landing of our house in London on the cold January morning after her funeral. He was examining a photograph of Lilla’s terrifying-looking first husband, his grandfather, that he had just hung on the wall. What a book it would make, he said. “It would be a sizzler. My God, she had a life.” But my father has written several books since then, and none of them have been about Lilla. Eventually, he handed me a pile of old photograph albums and a briefcase heavy with Lilla’s papers and documents, and the mantle passed to me.