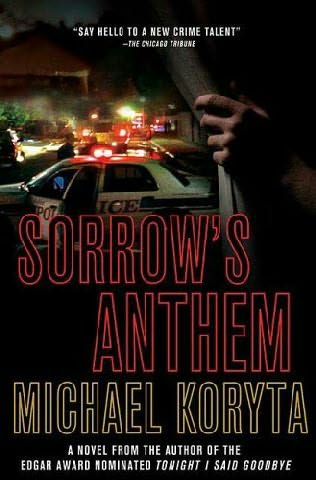

Lincoln Perry 02 - Sorrow's Anthem

Read Lincoln Perry 02 - Sorrow's Anthem Online

Authors: Michael Koryta

sorrow’s anthem

by

Michael Koryta

Koryta’s impressive second hard-boiled mystery is a worthy successor to his debut, Tonight I Said Goodbye (2004), an Edgar and Shamus finalist. Cleveland

PI Lincoln Perry, haunted by the circumstances that led to his estrangement from his best friend, Ed Gradduk, clutches at an opportunity for redemption

on learning that Gradduk is a fugitive from the law, suspected of arson and murder. Perry’s hopes of repairing their relationship are dashed after his

childhood confidant dies in an accident. As a result, Perry shifts his mission to clearing the dead man’s name. Perry, aided by his partner, follows a

winding trail of dirty cops and multiple suspicious fires toward the truth. The 22-year-old author, who works for a PI and for an Indiana newspaper, displays

credible insider knowledge of those professions as well as a gift for creating both sympathetic characters and a fast-moving, twisty plot.

Also by Michael Koryta

Tonight I Said Goodbye

THOMAS

DUNNE

BOOKS

ST. MARTIN’S

MINOTAUR

fifi

NEW

YORK

To my parents, Jim and Cheryl Koryta, with love and gratitude

An imprint of St. Martin’s Press.

SORROW’S

ANTHEM

. Copyright Š 2006 by Michael Koryta. All rights reserved. Printed in the

United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever

without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in, enseal artrcks

or reviews. For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.minotaurbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Koryta, Michael.

Sorrow’s anthem / Michael Koryta.p.

cm.

ISBN

0-312-34010-9

BAN

978-0-312-34010-0 . .

First Edition: February 2006

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My editor, Peter Wolverton, deserves the foremost thanks, as he

remained confident that there was a book somewhere in the initial

mess, and gave me the time and guidance I needed to see it through.

Working with Pete and my agent, the supportive and insightful

David Hale Smith, is truly a pleasure. Thomas Dunne, John

Cunningham, and the rest of the team at St. Martin’s Press are

exceptional in every facet.

My early readers—Bob Hammel, Laura Lane, and Janice Rick-ert—were outstanding, and greatly appreciated.

My uncle, Kevin Marsh, of the Cleveland Metroparks Rangers,

provided insight into his department and the Cleveland law enforcement

community in general. He should not, however, be blamed

for any errors made or liberties taken by this writer.

Thanks also to Don Johnson of Trace Investigations, and to

Stewart Moon, Donita Hadley, and the rest of the Herald-Times gang.

During the year surrounding publication of my first book, a

number of writers whom I greatly admire went out of their way to

offer advice, encouragement, and support. Such opportunities were

without question the highlight of the first-book experience for me,

and I am greatly indebted to all of you.

As always, my family is the most appreciated, and I need to offer

a special note of thanks to my father, Jim Koryta, a Clark Avenue

original who made the near west side of Cleveland a place of stories

for me when I was young. It appears to have had a lasting effect.

PART

ONE

.

MEMORY

BLEEDING

CHAPTER

1

I heard the sirens, but paid them no mind. They were near, and

they were loud, but this was the west side of Cleveland, and while

there were many worse places in the world, it was also not the type

of neighborhood where a police siren made you do a double take.

“You ready, West Tech?” Amy Ambrose asked, taking a shot

from the free throw line that caught nothing but the old chain net

as it fell. Out here the nets were chain, not cord, and while they

could lacerate your hand on a rebound attempt, they sounded awfully

satisfying when a shot fell through, a jingle of success like a

winning pull on a slot machine.

“Of course I’m ready,” I answered, trying to match her shot but

clanging it off the rim instead. This didn’t bode well. Amy had

been challenging me to a game of horse all week, and I was distressed

to find she could actually shoot. I’d played basketball for

West Tech in the last years of the school, before the old building

was shut down, but it had been several months since I’d even taken

a shot. Amy had become a basketball fan in recent years, more inspired

than ever since LeBron James had arrived in Cleveland, and

I had a bad feeling that I was about to become the latest victim of

her new hobby.

'I hope you’ve got a better touch than that when you actually

need it,” Amy said of my errant effort.

“I was always more of a point guard in high school,” I said. “You

know, a distributor.”

So you couldn’t shoot,” Amy said, hitting another shot, this one

from the baseline. She pointed at her feet. “You’ve got to make it

from here.”

I missed. Amy grinned.

“You’ve got an 'H’ already, stud. Looks like this will be a short

one.” She was about to release her next shot when her cell phone

rang with a shrill, hideous rendition of Beethoven’s Fifth. She

missed the shot wide, then turned to me with a frown. “Doesn’t

count. The cell phone distracted me.”

“It counts,” I answered. “You ask me, you should be penalized a

letter just for having that ring on your phone.”

She let the phone go unanswered. I took a shot from the three

point line and made it. Amy missed, and we were tied at “H.” Her

phone rang again, turning the heads of a few of the kids who were

hanging out at the opposite end of the court. We were playing at

an elementary school not far from my apartment.

“I’m not losing to you, Lincoln,” Amy said as I hit another shot.

She continued to ignore the phone, which was on the ground behind

the basket, and eventually it silenced. After a long moment

of focusing, she took the shot and made it, forcing me to try

again.

We traded makes for a few minutes, and then Amy pulled ahead

by a letter. We were both beginning to sweat now as we moved

around the court, the mugginess of the August day not fading as

fast as the sun. Amy looked like a teenager in her shorts and

T-shirt, with her curly hair pulled back into a ponytail. A couple of

boys who were maybe sixteen went past on skateboards and gave

her a long, approving stare.

“Your shot,” Amy said after she finally missed one. “Make it interesting,

would you?”

I dribbled left and came back to the right, pivoted, and fired a

pretty fadeaway jump shot that caught the side of the backboard

and sailed out of bounds, a Michael Jordan move with Lincoln

Perry results.

“That was embarrassing even to watch,” Amy said.

“I won seven games with that move in high school, smart-ass.”

“Really?”

“No.”

Her phone began to ring again. I groaned.

“Just answer the damn thing or turn it off, Ace.”

“Okay.” She tossed the ball back to me and walked over to pick

up the phone. While she talked, I stepped outside the three-point

line and put up a few more long shots, missing more than I hit.

Amy hung up and walked back onto the court. She stood with

her hands on her hips, her eyes distant.

“What’s up?” I said, dribbling the ball idly with one hand.

“It was my editor. Big story breaking. He wanted to know if I

had a good source with the fire department.”

“Oh?”

“Involves your old neighborhood,” she said. “Any chance you

want to ride down there with me and do some reporting? Maybe

you could hook me up with a good source or two.”

I smiled. “You’re way too suburban to be hanging out in my old

neighborhood, Ace.”

“Shut up.” Amy likes to think of herself as tough and street

savvy, and she hates it when I hassle her about her childhood in

Parma, a middle-class suburb south of the city. I was west side all

the way.

“What’s the story?” I took another jump shot and hit it.

“Murder.”

“That does sound like the old neighborhood.” I retrieved the

ball and dribbled back to the top of the key, my back to Amy.

“Some guy set fire to a house down on Train Avenue with a

woman inside. Dumbass was caught on tape, though. A liquor

store surveillance camera from across the street, I guess. When the

cops went to arrest him this evening, he fought them and got

away.”

“Remember the sirens we heard earlier?” I said.

“That could’ve been the reason for them. Guy who set the fire

lives up on Clark Avenue. I thought you grew up off Clark.”

“That’s right.” I took another shot. “What’s the guy’s name?”

“Ed Gradduk.”

The ball hit hard off the back of the rim and came bouncing

straight at me. I let it sail past without even extending a hand. It

rolled to the far end of the court, but I kept my eyes on Amy.

“Ed Gradduk,” I said.

“That’s how my editor pronounced it. You know him?”

The sun was all the way behind the school now, the court bathed

in shadows. The ball lay still about fifty feet behind us. I walked

across the court, picked it up, and brought it back to Amy. She was

watching me with raised eyebrows.

“You okay?”

“I’m okay,” I said. “Here’s your ball. Listen, I’m sorry, but I need

to leave. Consider it a forfeit if you want. We’ll have a rematch

some other time.”

She took the ball and frowned at me. “Lincoln, what’s the problem?

Do you know this guy?”

I wiped sweat from my forehead with the back of my hand and

looked off, away from the orange sunset and toward the shadows

east of us. Toward Clark Avenue.

“I knew him. And I’m sorry, but I’ve got to go, Ace.”

“Go where?”

“I need to take a walk, Amy.”

She wanted to protest, to ask more questions, but she didn’t. Instead

she stood alone on the basketball court while I walked away.

I went around the school building and out to the street, got inside

my truck, and started the engine. The air conditioner hit me with a

blast of warm air and I switched it off and lowered the windows

instead. It was stuffy and hot in the truck, but the trickle of sweat

sliding down my spine was as cold as lake water.

It’s early summer. I’m twelve years old, as is Edward Nathaniel

Gradduk, my best friend. We are spending this night as we’ve spent

every night so far this summer: playing catch in Ed’s front yard. The

yard is narrow:, as they all are on Clark Avenue, so we begin our game

in the driveway. As the night grows late, though, the house and the trees

block out the remains of the sun, and we move into the front yard to

prolong things. Here, with the glow of the streetlight, we can play all

night if we want to. The ball is difficult to see until it is right on you, but

we’ve decided this is a good practice element, calling for faster reflexes.

By the time we get to high school, we’ll have the best reflexes around, and

from there it will be a short trip to the major leagues. High school, to us,

seems about as real a possibility as the major leagues this summer; a

dreamworld with driver’s licenses and cars and girls with breasts.

''Pete Rose is a worthless piece of shit,” Ed says, whipping the

ball at me with a sidearm motion. “I don’t care how many hits he

has.”

“Damn straight,” I reply, returning the throw. Ed and I are Cleveland

Indians fans, horrible team or not, and if you’re a Cleveland Indians

fan you hate Pete Rose. You hate him because he is a star player

in Cincinnati, a few hours to the south, but more than that, you hate

him because he ran into Ray Fosse at full speed in an All-Star game

more than a decade ago and Ray was never the same after the collision.

Thirty years after the team s last pennant, a player like Ray Fosse

means a lot to Indians fans. He is another bust now, another hope extinguished,

but for this one we get the satisfaction of blaming Pete Rose.

“My dad said he’d like to see Pete Rose come up to Cleveland and go

into one of the bars,” Ed says. “Said he’d get his ass kicked so fast it

wouldn’t even be funny. 'Cept it would be funny, you know? Funnier

than shit.”

Ed has a way of talking just like his old man, which explains the

persistent profanity. My own dad would clock me if he ever heard me

swearing like we do, but when I’m with Ed, it’s safe. Cool, even. A

couple of tough guys.

“Damn straight,” I say again, a tough-guy phrase if ever there was

one. “I wish I could be there to see it.”

“Pete’ll never come to town,’' Ed says. “Doesn’t have the balls.”

Ed lives on Clark Avenue, and I live with my father in a small

house on Frontier Avenue, just south of Clark. Our wanderings carry

us as far east as Fulton Road, and a favorite spot is St. Mary s Cemetery

on West Thirty-eighth. Sometimes EdandI run through the cemetery

at night, telling each other ghost stories that start out seeming corny

but end up making us sprint for home. Ed’s mother is always at home;

my mother has been dead since I was three. I have a framed picture of

her on the table beside my bed. The first time Ed saw it, he frowned and

asked why I had a picture of my mother in my room. I told him she was

dead, flushing with a mix of shame and anger—ashamed that I was

embarrassed to have the picture out, and angry that Ed was challenging

it. He looked at it judiciously, touched the edge of the frame gently

with his finger, and said, “She was real pretty.” From then on, Ed

Gradduk has been my best friend.