Lincoln (121 page)

Authors: David Herbert Donald

When Major Rathbone tried to seize the intruder, Booth lunged at him with his razor-sharp hunting knife, which had a 7¼-inch blade. “The Knife,” Clara Harris reported, “went from the elbow nearly to the shoulder, inside,—cutting an artery, nerves and veins—he bled so profusely as to make him very weak.” Shoving his victim aside, Booth placed his hands on the balustrade and vaulted toward the stage. It was an easy leap for the gymnastic actor, but the spur on his heel caught in the flags decorating the box and he fell heavily on one foot, breaking the bone just above the ankle. Waving his dagger, he shouted in a loud, melodramatic voice:

“Sic semper tyrannis”

(“Thus always to tyrants”—the motto of the state of Virginia). Some in the audience thought he added, “The South is avenged.” Quickly he limped across the stage, with what one witness called “a motion ... like the hopping of a bull frog,” and made his escape through the rear of the theater.

Up to this point the audience was not sure what had happened. Perhaps most thought the whole disturbance was part of the play. But as the blue-white smoke from the pistol drifted out of the presidential box, Mary Lincoln gave a heart-rending shriek and screamed, “They have shot the President! They have shot the President!”

The first doctor to reach the box, army surgeon Charles A. Leale, initially thought the President was dead. With his eyes closed and his head fallen forward on his breast, he was being held upright in his chair by Mrs. Lincoln, who was weeping bitterly. Detecting a slight pulse, the physician ordered the President to be stretched on the floor so that he could determine the

extent of his injuries. Finding his major wound was at the back of his head, he removed the clot of blood that had accumulated there and relieved the pressure on his brain. Then, by giving artificial respiration, he was able to induce a feeble action of the heart, and irregular breathing followed.

As soon as it was clear that instant death would not occur, the President was moved from the crowded theater. Some wanted to take him to the White House, but Dr. Leale warned that he would die if jostled on the rough streets of Washington. They decided to carry him across Tenth Street to a house owned by William Petersen, a merchant-tailor. There he was taken to a small, narrow room at the rear of the first floor. Because Lincoln was so tall, his body could not fit on the bed unless his knees were elevated. Finding that the foot of the bedstead could not be removed or broken off, the doctors placed him diagonally across the mattress, resting his head and shoulders on extra pillows. Though he was covered by an army blanket and a colored wool coverlet, his extremities grew very cold, and the physicians ordered hot-water bottles.

Here Lincoln lay for the next nine hours. Dr. Leale and Dr. Charles S. Taft, who had also been in the audience for

Our American Cousin,

were constantly in attendance, and during the night, as Taft noted, “nearly all the leading men of the profession in the city tendered their services.” When Dr. Robert King Stone, the Lincolns’ family doctor, arrived at about eleven o’clock, he became the physician in charge, and he consulted with Dr. Joseph K. Barnes, the surgeon general of the United States. From the first, all of them agreed that there was no chance of recovery. The doctors agreed that the average man could not survive the injury Lincoln had received for more than two hours, but Dr. Stone noted that the President’s “vital tenacity was very strong, and he would resist as long as any man could.” He never regained consciousness.

Mary was with her husband through the long night. Frantic with grief, she sat at his bedside, calling on him to say one word to her, to take her with him. When Robert came in with Senator Sumner, he saw what desperate shape his mother was in and sent for Elizabeth Dixon—wife of Connecticut Senator James Dixon—who was perhaps Mary’s closest friend in the capital. Mrs. Dixon persuaded her to retire to the front room of the Petersen house, where she rested as well as she could, returning every hour to her husband’s side. On one of these visits she sobbed bitterly, “Oh, that my little Taddy might see his father before he died!” but the physicians wisely decided that this was not advisable. Once when Lincoln’s breathing became very stertorous, Mary, who was approaching exhaustion, became frightened, leapt up with a piercing cry, and fell fainting on the floor. Coming in from the adjoining room, Stanton called out loudly, “Take that woman out and do not let her in again.”

During the night, as crowds gathered in the street in front of the Petersen house, all the members of the cabinet except Seward came to see their fallen chief. Much of the night Secretary Welles sat by the head of the

President’s bed, listening to the slow, full respiration of the dying man. Vice President Johnson was summoned, but Sumner urged him not to stay long, knowing that Mary Lincoln detested him and might cause a scene. The Reverend Phineas D. Gurley, pastor of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, which the Lincolns frequently attended, came to give spiritual comfort.

Stanton promptly took charge. Making an adjacent room in the Petersen house his headquarters, he summoned Assistant Secretary of War Dana to help him and began rapidly dictating one order after another designed to keep the government functioning during the crisis. Stanton immediately started an investigation of the assassination, taking testimony from witnesses, ordering all bridges and roads out of the capital closed, and directing the military to search for the murderers. By dawn he had a massive manhunt under way. He soon learned that there had been not one but two assaults. Though Atzerodt decided not to attack Andrew Johnson and spent the night wandering aimlessly about the city, Paine, following Booth’s directions, had burst into Seward’s house; he fiercely attacked the Secretary of State, who was still bedridden after his carriage accident, and left him bleeding copiously and barely alive. By morning Paine and Atzerodt were under arrest, and the other conspirators—including those who had only been involved in the kidnapping plot—were promptly seized. But Booth, who was accompanied by Herold, escaped. Not until April 26 did Stanton’s men trace him to a farm in northern Virginia, where he was shot.

Long before that, Lincoln was dead. As the night of April 14–15 wore on, his pulse became irregular and feeble, and his respiration was accompanied by a guttural sound. Several times it seemed that he had ceased breathing. Mary was allowed to return to her husband’s side, and, as Mrs. Dixon reported, “she again seated herself by the President, kissing him and calling him every endearing name.” As his breath grew fainter and fainter, she was led back into the front room. At twenty-two minutes past seven, on the morning of April 15, the struggle ended, and the physicians came in to inform her: “It is all over! The President is no more!”

In the small, crowded back room there was silence until Stanton asked Dr. Gurley to offer a prayer. Robert gave way to overpowering grief and sobbed aloud, leaning on Sumner for comfort. Standing at the foot of the bed, his face covered with tears, Stanton paid tribute to his fallen chief: with a slow and measured movement, his right arm fully extended as if in a salute, he raised his hat and placed it for an instant on his head and then in the same deliberate manner removed it. “Now,” he said, “he belongs to the ages.”

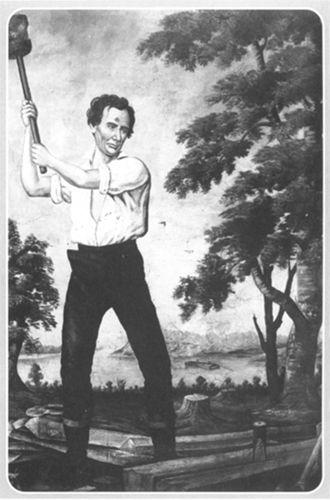

“THE RAILSPLITTER”

This 1860 life-sized oil painting, by an unknown artist, suggests the mythic qualities that helped elect Lincoln President. Forgotten here are Lincoln’s highly successful law practice and his career in politics in order to stress, in a frontier setting, the homely virtues of physical strength and hard manual labor.

Chicago Historical Society

Sarah Bush (Johnston) Lincoln (1788-1869). Lincoln’s stepmother was one of the most powerful influences in his life. In her old age, when this photograph was taken, she recalled: “Abe was a good boy. . . . His mind and mine, what little I had, seemed to run together . . . in the same channel.”

Meserve-Kunhardt Collection

Mary Lincoln, around 1846. This is the earliest daguerreotype of Mrs. Lincoln, made, as she said, “when we were young and so desperately in love.”

The Library of Congress

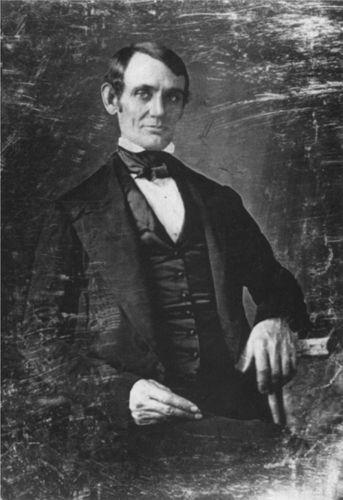

Abraham Lincoln, around 1846. Made at the same time as the portrait of Mary Lincoln, this daguerreotype was probably the work of N. H. Shepherd, one of the first photographers in Springfield, Illinois.

The Library of Congress

John Todd Stuart

Courtesy of the Illinois State Historical Library, Springfield