Listen to the Squawking Chicken: When Mother Knows Best, What's a Daughter To Do? A Memoir (Sort Of) (7 page)

Authors: Elaine Lui

So I came home at one o’clock. How can you argue with that? Even if I didn’t think she gave me the best life, she did actually give me life—the most basic, important gift of all. And in doing so she deserves to be repaid for it. With obedience first . . . and then cash later. Or jewelry. Or cruises.

The first time I ever spent my own money on Ma it was for a pair of gold hoop earrings. I was twelve. My parents were divorced. They’d split up just before my seventh birthday and Ma had moved back to Hong Kong and remarried, leaving me in the care of my father. I visited her at Christmas, spring break and on summer holidays.

That year, she’d come back to Canada for a friend’s wedding. We were at the mall with some relatives shopping for a wedding gift. I’d just started getting interested in clothes and wanted to buy an expensive dress that was totally impractical. She wouldn’t buy it for me so I told her that I wanted to use my

lai see

and birthday money to buy it for myself. She still wouldn’t let me because she said it was a stupid use of my savings. Furious and embarrassed to be shut down in front of other people, I told her that she had no right to tell me what

to do since she had bailed on me to fuck off with another man. It was a sucker punch I’d been waiting six years to hit her with.

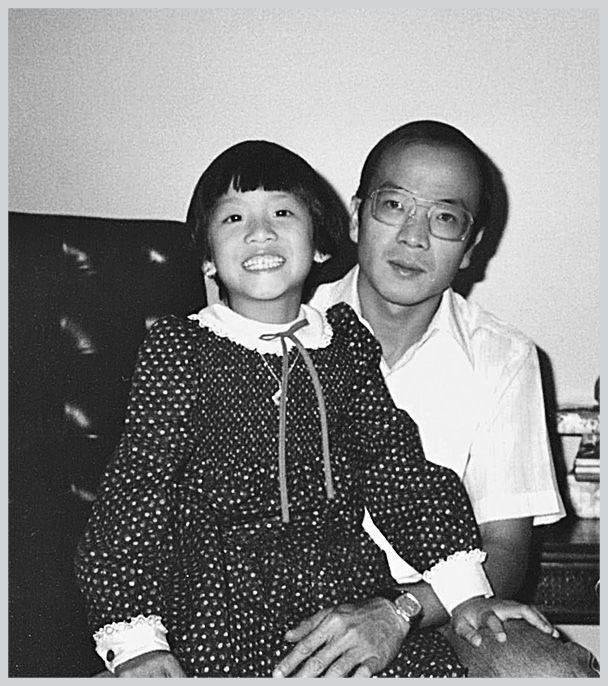

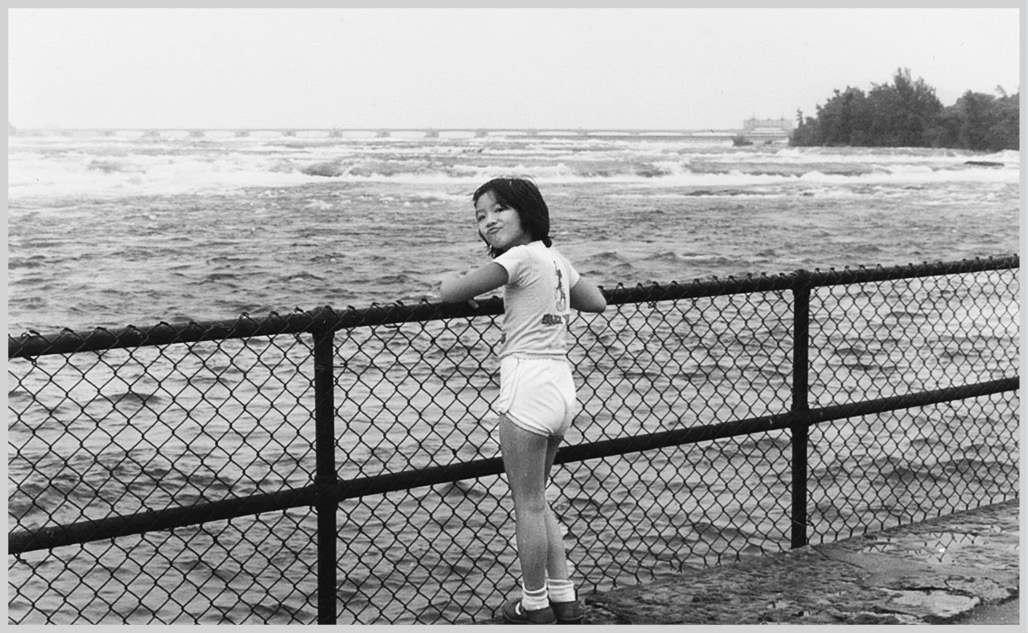

I had a hard time after my parents’ separation. Ma called me regularly after she first left and, every couple of months, a big box would arrive from Hong Kong full of toys and clothing. It would be a year before I saw her again and in that time, I felt her absence inside and outside of our home. I was at that age when parents are actively involved in their children’s lives at school. There were parent-teacher conferences. There were recitals and Christmas concerts. Most of the other kids had two people waiting for them at all times. And the few kids whose parents were divorced, like mine, were picked up by their mothers. At that time, in the early eighties, it was socially assumed that all kids had two parents.

On school release forms it was always the word “parents,” never the “parent or guardian” phrasing that’s become commonplace today. And if any parent was singled out for any reason, it was always the mom. “When you get home tonight, remind your mom that tomorrow is baked goods day for the charity drive so she should pack an extra cookie with you for lunch.” Dad was among the first wave of single fathers. And while it’s awesome to think of him as a trailblazer now, back then it only made me more different. I was the only Chinese girl in my class. I was the only girl in class with just a dad.

But if it was uncomfortable for Dad to be both father and mother to me during those years, he never let on. He was never late, he was never disorganized, he was always there, a

dutiful father whose love had to fill a Squawking Chicken–sized gap.

So when Ma denied me the dress in the mall that day, my tantrum was part adolescent resentment combined with parental preference. Up to then, my loyalties were with Dad. It felt good to hurt her.

Ma’s eyes narrowed. For once, the Squawking Chicken did not squawk. When the Squawking Chicken isn’t squawking, she’s either almost dead or you know you’re in some deep shit. My family members disappeared. Ma turned on her heel, knowing I would follow. She took me to a coffee shop, ordered a cup of coffee, and asked me if I wanted one too. I did. It felt very grown-up. And, indeed, we had a very grown-up conversation. Ma decided to tell me about the history of her relationship with Dad, and why she left him.

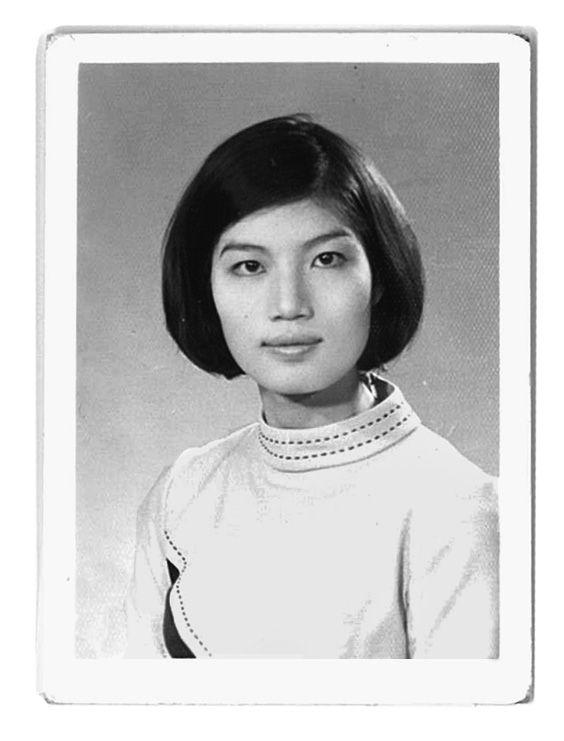

Ma had dropped out of school after Grade 10 to support her family. Without a proper education, there was only so much she could do. At first she made money placing bets for people at the track and collecting tips. From there, having made connections with local trading merchants who used to hang out at the gambling halls, she worked for them under the table, organizing shipping orders and schedules for Western

goods to cross on the black market into China. Later on, she got a job at a real estate firm selling overseas property. The commission was great. She booted around in a BMW, bought clothes in Kowloon, traveled throughout Asia and still had enough money to send home every week.

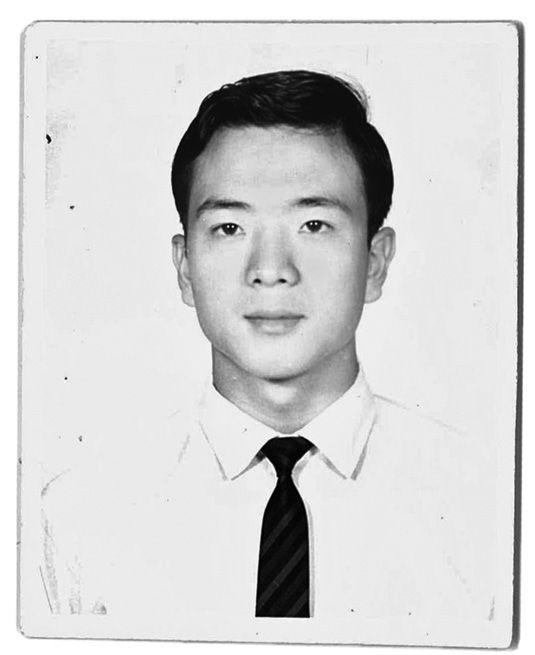

While Ma was a single girl hitting her stride, Dad was just getting started. He was a poor farmer boy from Tsuen Wan, a small town about half an hour away from Yuen Long, the sixth of ten children, shy and unsophisticated. As a boy and through his teen years, he was mentored by a monk who taught him Buddhist scripture and impressed upon him the value of hard work and perseverance. For a while, he considered entering the monastery himself. But meeting Ma changed everything.

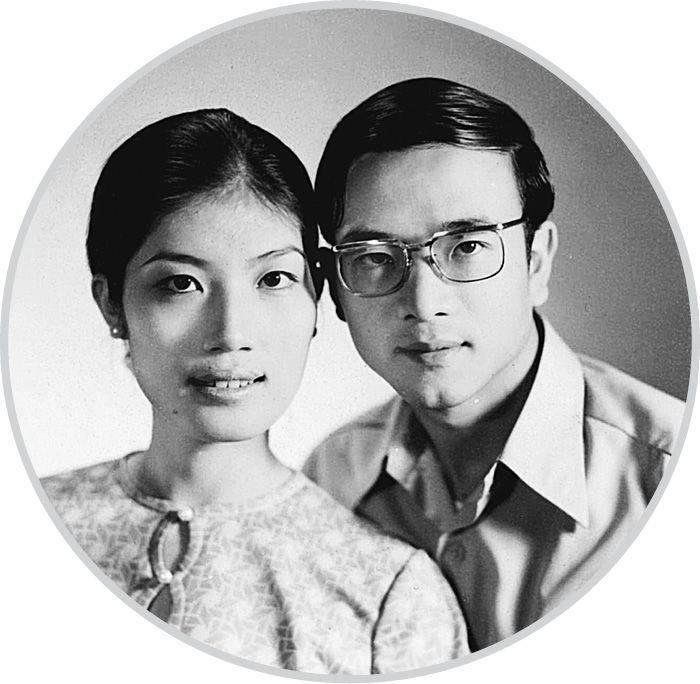

Dad had a job at the Yuen Long courthouse as a clerk. His supervisor, Mr. Lai, who would eventually become my godfather, recognized his potential and intended to promote him. Mr. and Mrs. Lai were good friends with the Squawking Chicken. They all played mah-jong together. Ma would occasionally visit Mr. Lai at the courthouse. She’d pull up in her BMW, strut across the office like she owned it, squawking her arrival as if everyone should stop working because she was there. Dad was instantly infatuated. Or, as she put it, “Your daddy couldn’t even dream that he’d ever meet someone as amazing as me.” Since Dad didn’t have the nerve to ask her out, Mr. Lai kept trying to set them up. Ma saw it as a charitable opportunity, a kindness she was bestowing just once on this hillbilly with the glasses and the nerdy clothes.

She wouldn’t go out with him again after their first date. The Squawking Chicken had an active social life. She was smart, well connected, popular and well-dressed, and after years of family drama, the situation at home was finally stabilized. She had opportunities. She had plans. And Dad was a total nerd—shy and awkward, he wore goofy clothes and had country manners. “Your daddy only knew how to eat chicken! Only chicken and rice! And my underwear cost more than his entire wardrobe.” He didn’t fit into her world.

But he refused to be put off. So one night he stood outside her window, across the street so she could see him, from after dinner until morning, just to demonstrate his ardor. People made fun of him as they passed. He looked pathetic—the geek pining for the girl who was out of his league, the clueless loser who couldn’t take a hint. It was a John Hughes movie. But it worked. Dad wore her down. He made Ma feel like she was the only woman who mattered, like she was worth fighting for. They fell in love over the objections of her parents who, by this point, had conveniently whitewashed their lives. There was no more drinking. There was no more adultery. Her father was now a bus driver. Her mother stayed home to look after Ma’s siblings, which basically meant she played mah-jong all day while Ma helped them with their household expenses. Her parents were enjoying her generosity and the fact that she was successful was

making them look good. They were hoping she’d hook up with a rich businessman who could support them too. So when they found out that Ma was dating some hick with bad clothes and no car, they were disappointed. They thought Dad was beneath her, beneath

them

.

But Ma believed in Dad. She knew he was tenacious and hardworking. She encouraged him to pursue night classes and advance through the government employment system. They were married a year after they met and moved into a modest but comfortable apartment in a good neighborhood. They were young and excited and he had a promising career ahead of him. He earned enough so that Ma didn’t have to work anymore. She had never been happier.